Mary Baliker, a 58-year-old kidney transplant recipient living in Middleton, Wisconsin, is no stranger to blood tests. But this one was different. As part of a clinical study on antibody responses, she has been periodically FedEx-ing her blood to Johns Hopkins, where doctors have been looking for immune responses to the Moderna vaccine. Because she takes immunosuppressive drugs so her body doesn’t reject the donated organ, it wasn’t very likely that the vaccine would prompt the immune response it is supposed to. Nevertheless, she held out hope. When the final results came back—negative, no antibodies—she was heartbroken. “I guess all my fear of not building antibodies had just been proved,” she said. “I was discouraged. I just tried not to think about it.”

Baliker is one of many Americans whose immune systems are weakened either because of disease or because of the medications used to treat disease. It’s tricky to tally the exact number of the immunocompromised, which includes people with a wide range of conditions—not only transplant patients but also people with arthritis, HIV/AIDS, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and cancer. A recent estimate puts the proportion of privately insured adults ages 18 to 64 on immunosuppressives at 2.8 percent, or some 3.6 million Americans. But Dr. Beth Wallace, a rheumatologist at the University of Michigan Medical School who authored the study, said this estimate didn’t account for those on Medicare or Medicaid, nor did it count innately immunocompromised adults not on immunosuppressives. She noted pinning down the true number of Americans with weakened immune systems is surprisingly difficult, but some experts I spoke with thought it could be as high as 10 million or even 15 million.

To put that in perspective, if the immunocompromised were a state, it would be the fifth largest in the nation—about the size of Pennsylvania. If they all worked in the same industry, they’d be the size of the hospitality labor force. There are about as many immunocompromised people as there are Americans over 80 years of age. You might not know it—or might not have known it until recently—but if you know someone from Pennsylvania, if you know someone who works at a restaurant or a hotel, or if you know someone over 80, you’re just as likely to know someone who’s immunocompromised. If you include the people who live or are in regular contact with the immunocompromised—spouses, children, relatives, roommates—then it becomes clear that this is not a small sliver of America.

Which is why—even though vaccines are on the verge of being authorized for kids, and boosters could be authorized for everyone in a matter of months—we need to consider how the pandemic is going for the many Americans who still must face it immunologically unarmed. As the delta variant circulates, the stakes are even higher. Take transplant patients like Baliker: According to a recent study, transplant recipients are 82 times more likely to get a breakthrough infection, and 485 times more likely to be hospitalized or die. For this group, breakthrough infections aren’t a source of anxiety; they’re a mortal threat: A positive COVID test means they face a 1 in 10 chance of death.

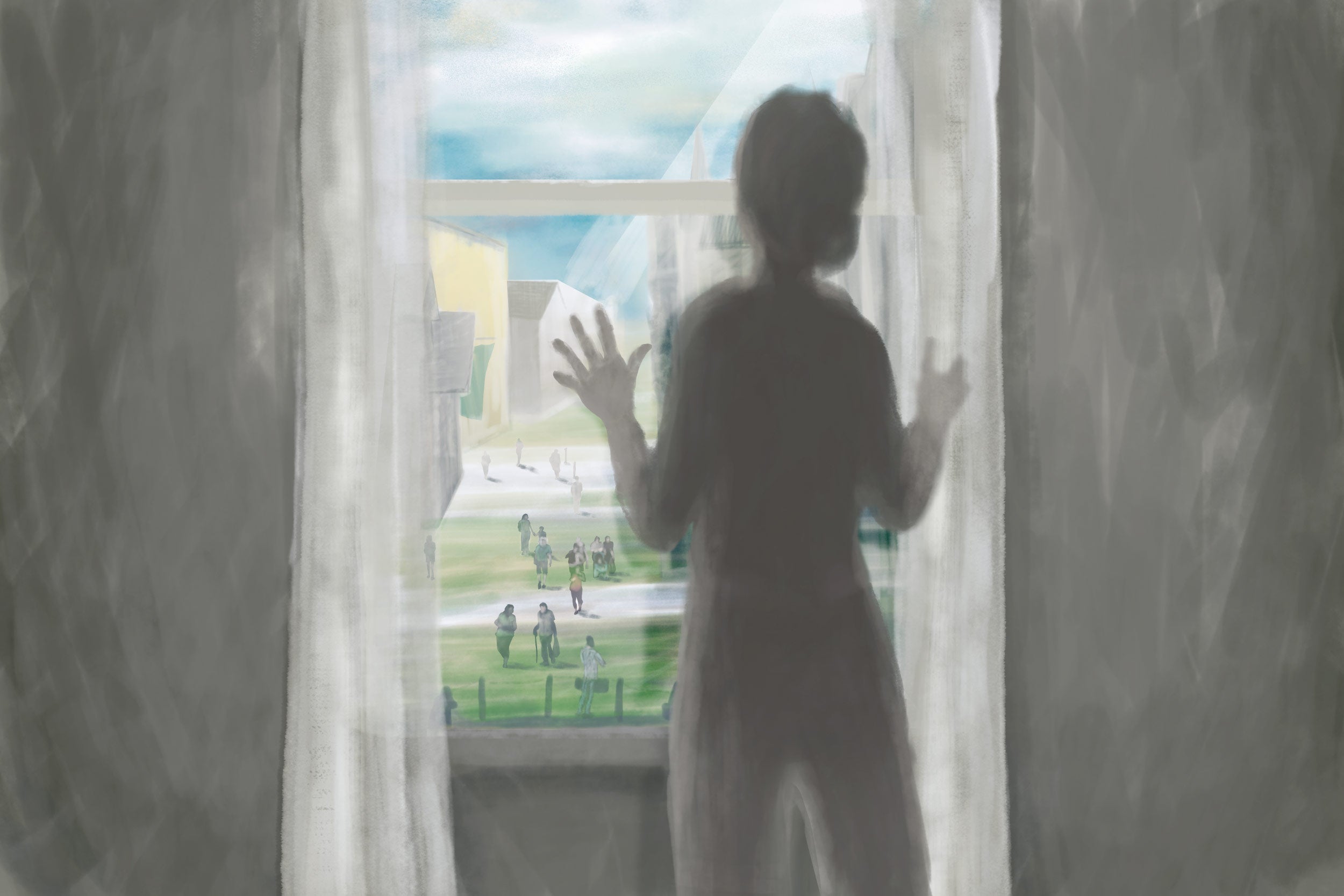

What’s next for immunocompromised people—what the pandemic easing really looks like for them—is a complicated puzzle. Many people, worn down from pandemic restrictions, seem to no longer want to hear about the enormous group of people that the progress with COVID vaccines has been leaving behind. “Sometimes it gets to the point that you feel a little bit marginalized, and that no one cares about people like me who are higher risk,” Baliker told me. As COVID becomes an ever-present feature of our lives, she wonders, “What exactly is the plan for us?” The real answer to that question lies in a patchwork of surprising—and, to some, controversial—solutions that are just beginning to come into focus.

Not all immunocompromised patients are as vulnerable as transplant patients, especially after vaccination. However, because the immunocompromised were left out of the original vaccine trials, scientists have had to play catch-up to determine exactly how much protection immunization might offer. Dr. Dorry Segev, director of the Epidemiology Research Group in Organ Transplantation at Johns Hopkins, has spent the past year and a half furiously studying this question. In 2021 alone, he’s published nearly 40 papers on the topic, and he recently received a $40 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the effect of booster shots in kidney transplant patients like Baliker. “It’s been a real black box, but we’re starting to make progress,” he said.

In March, Segev published a pair of studies showing only half of kidney transplant recipients produced an antibody response even after the second dose of an mRNA vaccine. In a small study on Johnson & Johnson vaccine recipients, only two of 12 transplant recipients produced antibodies. As for boosters, Segev collected antibody counts of transplant recipients who sought out third doses this spring, before boosters were authorized by the Food and Drug Administration. Of those who didn’t respond to the first two shots, only a third responded to the booster—which is in line with estimates from a larger study from France. What these studies suggest is that a significant number of transplant recipients, like Baliker, are left without any antibody protection even after multiple attempts at inoculation.

People with other conditions fare better, although results are mixed. People with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis generally produced antibodies in response to the first dose of an mRNA vaccine, although consensus is emerging that those taking widely prescribed drugs that suppress B cell function, such as rituximab, are far less likely to do so. A case series suggested that some patients with lupus, myositis, vasculitis, and Sjogren’s syndrome who take certain drugs do not develop antibodies at all. People with blood cancers may also have significant difficulty mounting an immune response. A French study found that only half of blood cancer patients produced antibodies, although it’s highly dependent on the type of blood cancer. According to a study led by researchers at the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, only 44 percent of patients with mantle cell lymphoma produced antibodies, but 99 percent of Hodgkin lymphoma patients did. Out of all blood cancer nonresponders given boosters, 33 percent still failed to produce antibodies. Although there’s more to the immune system than antibodies, it’s almost certain that large numbers of people have diminished or no protection, even after a booster shot.

Segev estimates there’s probably at least a million or so people who will need some sort of protection beyond the vaccine. We’re in wave four now, he said, “but what happens at wave 11? I’m healthy and vaccinated, so I’ll just wear masks in the grocery store. And if I get sick, it won’t be that scary.” But, he said, “many immunocompromised will have to put their entire lives on hold again, or risk death.”

They know that. And as with so many things about this pandemic, they also know it didn’t have to be this way. For other infectious diseases, such as measles and polio, the immunocompromised are protected because the rest of us are vaccinated, creating herd immunity, that situation in which new outbreaks fizzle instead of spiraling out of control. When COVID vaccines arrived on the scene, many grew hopeful that Americans would rise to the occasion and get immunized to protect society’s most vulnerable. Those hopes were dashed as politicization and disinformation fueled widespread vaccine refusal.

And the immunocompromised are really getting fed up with this state of affairs. I spoke with Dr. Larry Saltzman, a leukemia patient who is also a former family practice physician. He’s currently principal investigator of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s National Patient Registry, and he published two of the studies above. When he was vaccinated earlier this year, his body didn’t seem to produce any measurable antibody immune response. “It’s essentially as if I’m vaccinated, yet I don’t really have a defense against COVID.” This means he’s never been able to let up precautions. “My blood cancer has caused me and my wife to be far more sheltered than any of our friends. I haven’t seen my mother, who’s 89, since March 2020.”

Saltzman assumed the availability of effective, free vaccines would enable his community to step up for him. But where he lives, in Sacramento, California, the vaccination rate was only about 50 percent when it started leveling off (though mandates’ recent success might start to change this for the better). “Frankly, I’m very angry. Really angry. Herd immunity—and I hate saying this because I don’t want to sound selfish or self-serving—it’s to protect people like me because I am so vulnerable to this thing.” Professionally, he’s at a loss too. “In my role here, I’ve heard from people who have [since] died from COVID, I’ve heard of people who’ve come down with COVID, they’ve been hospitalized. They have long COVID, you know, and they’re just beside themselves. They don’t know what to do.”

Saltzman is fortunate because he can work from home and restrict his social contacts. But some people with blood cancer don’t have those choices. Dr. Gwen Nichols, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s chief medical officer who collaborated with Saltzman on the studies above, said that their information resource center is currently flooded with back-to-school concerns. Parents with blood cancers who have healthy children are nervous that their kids could bring the virus home from school, particularly in places where mask mandates are outlawed and vaccination rates are low. “People should realize that cancer doesn’t just affect old people. It affects people in the prime of their lives.”

That includes children. Leukemia is the most common pediatric cancer, affecting more than 41,000 children and teens, with most diagnoses between 2 and 5 years of age. “These are young kids who can’t get vaccinated, and it’s tragic that people around them might expose them when they’re already struggling so hard to have a life,” Nichols said. “If I was a parent of a kid with leukemia, I’d be really mad at anyone who didn’t want to help that kid survive.”

Saltzman’s and Nichols’ anger and disappointment were echoed by Dr. Shilpa Venkatachalam, associate director of patient-centered research at the Global Healthy Living Foundation, a nonprofit that supports and advocates for people living with chronic medical conditions such as arthritis. This August, the foundation surveyed 2,137 of its members about the rise of the delta variant. Before delta, some members were cautiously resuming their favorite activities for the first time in over a year, such as going to restaurants or socializing indoors. But when delta arrived, they had to dial those activities back again. In the survey, multiple members reported feeling “sad” and “angry” that people won’t get vaccinated. The relentlessness of the virus is taking a toll on them—and not just physically. “People living with these conditions have been isolated because that’s the way they can keep themselves safe,” Venkatachalam said. “And that isolation then has mental health impacts.”

Venkatachalam, who lives with arthritis, is hopeful that some of the flexibility afforded to the immunocompromised during the pandemic could at least herald a cultural change in accommodations for people who may not administratively qualify as disabled. “During COVID, there were work accommodations for many people,” she said. “A long-term concern for our community is, will there continue to be flexibility by employers for people living with autoimmune inflammatory conditions?” Those affected need permanent remote work options, flexible commute times to avoid crowded public transportation, and for insurance companies to continue pandemic-era policies like covering telehealth (though there are already signs the latter is being walked back). When leaving your house entails significant risk, it just makes ethical sense to give people the tools to mitigate those risks, particularly because they are possible.

If the immunocompromised do catch COVID, more drugs and treatments could be on the horizon to help them. Merck just announced a promising antiviral, and monoclonal antibodies (which famously may have saved the ass of a certain former president) are already available. Monoclonal antibodies can also confer passive immunity, which protects those who can’t make antibodies themselves. [Editor’s note: Read this accompanying piece about how that works.] Monoclonals aren’t a permanent solution or a cure, more of an immunological loan, but for those at highest risk, they could even be given as a preventive measure—although not FDA-approved for this purpose yet. Data from AstraZeneca’s antibody compound seems promising, though, and the company has just applied to the FDA for emergency use authorization. But there are a few hitches. Monoclonal antibodies require blood infusions, and there isn’t a “limitless supply” of sites that can administer the drug, according to Dr. Emily Blumberg, director of transplant infectious diseases at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Because infusion sites are also used for treatments such as chemotherapies, she said, there could be logistical hurdles to getting the lifesaving treatment into arms in time.

Another more troubling hitch is that monoclonals are currently being rationed by the federal government because of short supply—in part because so many are being used to save the lives of the unvaccinated. And some politicians are cynically exploiting the treatment to sustain the political benefit of opposing vaccine mandates: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis cut a side deal with GlaxoSmithKline for monoclonals while undermining efforts to increase vaccination. This means this kind of scenario could be playing out in Florida and elsewhere: An immunocompromised patient lying in bed, dying, because an available, lifesaving treatment has been rerouted to the arms of people who’ve refused to be vaccinated. “It’s terrible that the immunosuppressed, who are vulnerable and desperate and doing anything they possibly can to seek protection, would be denied the only protective avenue that they have because people are refusing the vaccine, acting recklessly, getting infections, and then soaking up the monoclonal antibodies. That’s a disappointing thought for me,” said Segev, the Johns Hopkins transplant researcher.

So what are we to do? In terms of policy, Baliker, the kidney transplant patient, said she welcomes the vaccine mandates politicians like DeSantis oppose. “I know not everybody agrees with the government coming down and saying, if you have a hundred employees or more, that you need to get vaccinated, but I can’t tell you how happy I was when I heard that.” Apart from what looks to be a highly effective employer mandate, there’s a new bill proposing mandated vaccination for domestic travel, and Gov. Gavin Newsom of California just announced that all eligible children K–12 will have to be vaccinated before next fall. More mandates are expected to be announced in the coming weeks and months.

Baliker hopes these policies mean herd immunity is closer than it currently feels, and that she’ll soon be able to return to what were once everyday activities without fear. Baliker, who has endured four kidney transplants, said, “This isolation is the hardest thing I’ve ever done, not being able to do the things that everyone else does.” When I asked what she would want people to know about those in her position, she reminded people that they never really know for certain how long they will be able-bodied: “There’s a lot of people that are at risk, and it could be your family, or it could be yourself, or your friends.”

Nichols, the chief medical officer of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, put it more bluntly. That politicians don’t encourage people to get vaccinated or take basic public health precautions, she said, “just seems like a lack of empathy. Put yourself in someone else’s shoes for once.”