Lukas Flippo, Photo Editor

Though Yale initially froze faculty searches and salaries and is budgeting a $27 million operating deficit for the 2021 fiscal year, which ends on June 30, the University is still investing millions into a fund to pay for its science initiatives.

In recent years, Yale has prioritized the sciences. Provosts have cut expenses, generated surpluses and reinvested that money into a fund to pay for the ambitious new science infrastructure Yale announced last October, which includes construction of a new building for physical sciences and engineering. Despite last year’s temporary hiring freeze and the University’s budgeted deficit for fiscal year 2021, Yale has put $10 million of its more than $4 billion operating budget toward the science priorities and continued with planning for its new science buildings.

University administrators said Yale plans to construct its new science buildings largely on its own dime, without large in-advance donor contributions, an uncommon action they took because the sciences are such a high priority for Yale. Breaking ground on the neuroscience and physical sciences and engineering buildings puts the University on the hook for astronomical figures. The Physical Sciences and Engineering Building, or PSEB, set tentatively to open in 2026, is estimated to cost $398 million, with an additional $73.7 million for a garage. Though administrators expected the pandemic would delay construction by about a year, they are moving ahead with planning and expect to break ground in 2023.

“Over the last several years, we’ve been just trying to find the resources to allow us, starting with the science building that’s just opened and then PSEB and 100 College, we’ve just been trying to find the resources that will allow us to expand because we’ve been sort of woefully underinvested in certain areas of science,” said Vice Provost for Academic Initiatives Pericles Lewis.

To fundraise for the new science initiatives, the University is soliciting donations from its wealthiest and most generous alumni as part of a capital campaign — a fundraising push that each president launches once during their tenure — that prominently features the science priorities and how they can improve Yale’s ranking among global research universities. Much of the existing funding for the University’s new science initiatives comes from the Science University Funds Functioning as Endowment, which is currently valued at $310 million.

Five professors interviewed by the News, mostly in the humanities fields, expressed concern that Yale’s focus on funding the sciences comes at the expense of its robust humanities programs.

“The Yale administration collectively made up its mind some time ago to beef up the sciences, science and engineering especially,” Professor of History Carlos Eire said. “And they decided to commit resources to that, and that is fine. But what many humanities faculty feel is that this growth has come at the expense of the humanities.”

University President Peter Salovey has repeatedly emphasized Yale’s commitment to the humanities in interviews with the News and his communications with the community.

Funds and new buildings for the sciences

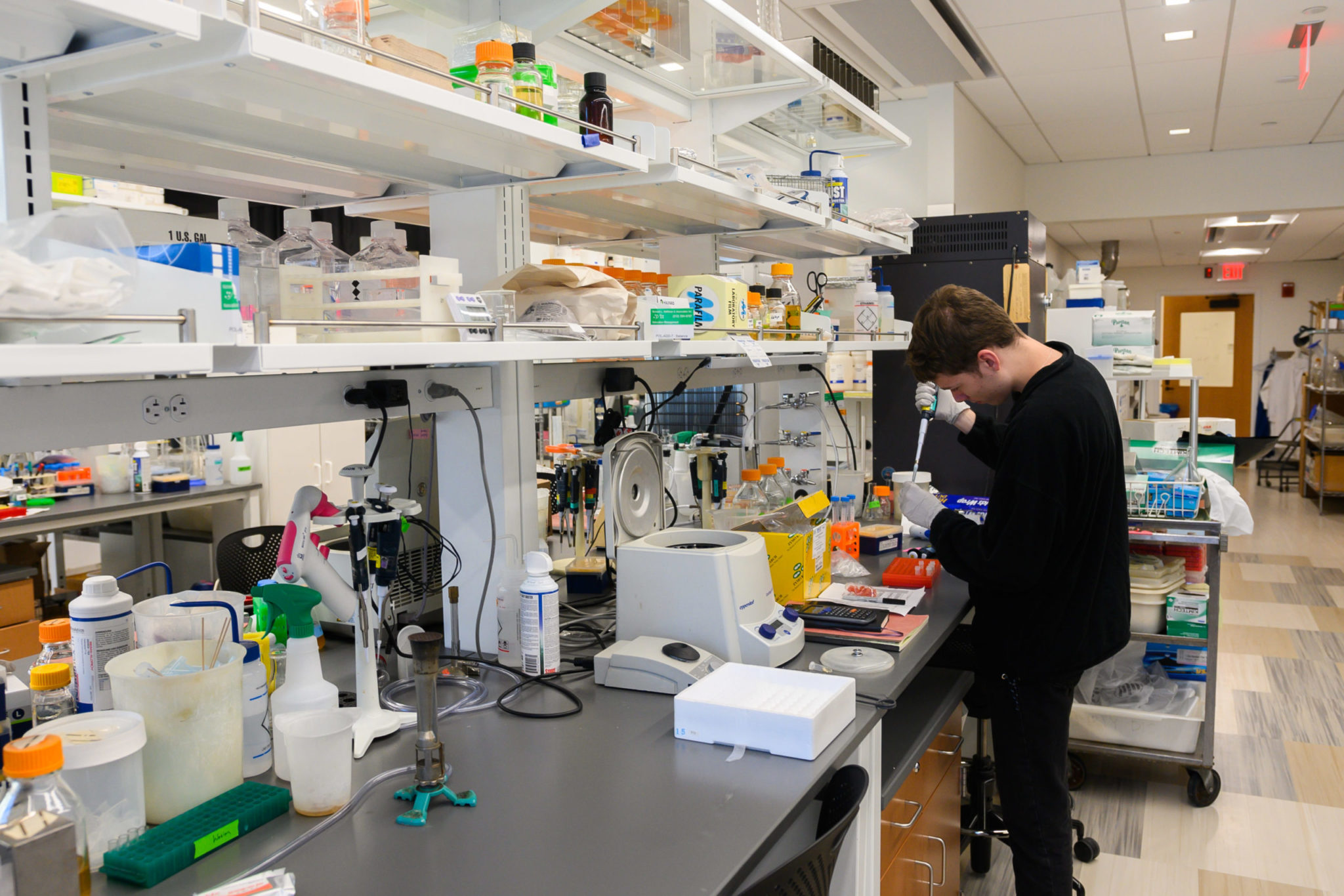

According to Lewis, professors’ research is usually funded by grants or by donors interested in the topic. But the grants do not pay for the lab space and equipment that multiple professors use for research. And donors are more interested in what the professors are working on than paying for the buildings.

“It is hard to raise facilities money, I will say,” Vice President for Alumni Affairs and Development Joan O’Neill said. “Doesn’t mean we won’t try … If you can raise some of it, then that’s just that much less that you have to borrow.”

The money for the buildings will come from bonds purchased by investors, endowment income, donations and Yale’s own funds, including $10 million from its operating budget for fiscal year 2021.

The money for the buildings will be added to the Science University Funds Functioning as Endowment, which was established in coincidence with Salovey’s 2016 announcement outlining University priorities and academic investments and will exist for at least 10 years. UFFEs are funds tied to capital projects. The University invests in short-term investments to grow those funds and raise more money for the capital projects. Though these funds are separate from the endowment, the Science UFFE is used to generate a steady stream of financial support for future science projects. As of the end of June 2020, the Science UFFE was valued at $310 million.

Yale can take $16 million each year from the fund to use immediately toward science initiatives, on top of the $10 million added this year and immediately available for expenditure.

According to financial records obtained by the News, the Science UFFE was “created to accumulate funds for future support of the ‘Academic Priorities’ science initiatives that might otherwise lack a source of ongoing funding.” The 2021 fiscal year budget did not include a similar investment into a fund for the humanities.

O’Neill said it has always been the University’s plan to use some institutional funds for the science priorities, as Yale cannot expect donors to cover the staggering costs associated with developing new science facilities. The new Yale Science Building that opened in 2019, which cost $283 million, was mostly paid for by the University taking on debt, she said.

Because constructing PSEB is such a high priority, the University is not waiting for a naming gift and is instead finding the resources to construct it, Lewis said. The University’s budget is in part built around the cost of construction. Strobel said that Yale is currently drawing up plans to make the building visionary. He is hopeful the project will attract one or more donors interested in the science priorities.

Since 2016, Salovey has repeatedly emphasized that Yale must catch up to its peers and raise its ranking in the sciences, as that is where the University falls farthest behind. University Provost Scott Strobel, who chaired the committee that laid out the science priorities, has allowed the planning for PSEB to continue during the pandemic, and faculty searches in the sciences are in the works or poised to start, according to Karsten Heeger, chair of the Physics Department and chair of the Physical Sciences and Engineering Building working group.

Although administrators expected the pandemic would delay PSEB construction by about a year, they are forging ahead with planning and expect to break ground in 2023.

In order to recruit top science professors, Yale needs to entice them with state-of-the-art infrastructure and lab space, according to Heeger. The investment in the Physical Sciences and Engineering Building will “send a very strong signal” that Yale aims to be, and will be, at the forefront of quantum science, Heeger said.

Lewis said that advancing in the sciences depends on both hiring top professors and having the space for professors to work. When donors give money to name a professorship, the University uses the money originally spent on the professor’s salary to pay for construction, according to Lewis.

Although Yale instituted a hiring freeze last spring, the University thawed it this fall and hopes to return to pre-COVID-19 hiring levels next year, Lewis said.

Should Yale specialize?

In an interview with the News, former senior trustee of the Yale Corporation Vernon Loucks ’57 outlined his vision for a strategic use of Yale’s funds to advance in a select few areas instead of trying to improve across the board. The University cannot be the best at everything, Loucks said, and ought to ask itself in which areas it hopes to truly excel.

Under former University President Richard Levin, the University would not start a new project unless it had the money for it “in the bank,” Loucks said. Yale already has open professorships it needs to fill, and he fears the University is spending ahead of its endowment.

“Don’t try to be great at everything just because somebody else has it,” Loucks said. “People will say, ‘Yale’s got a big endowment.’ Well, they do because they worked hard at it.”

Scott questioned whether the University can catch up to its peers that are historically far stronger in the sciences, saying that Yale will never remotely rival the California Institute of Technology, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology or Stanford as centers of scientific education.

Others point to the money. Developing top science programs is far more expensive than moving ahead in the humanities, as science requires lab space, equipment and trained staff to operate machinery. For most scientists, the cost of a hire is astronomically greater than in the arts and humanities because of the labs and infrastructure that each of them requires, James Scott, Sterling Professor emeritus of political science, wrote in an email to the News.

Professor of English David Kastan wrote in an email to the News that because the arts and humanities are comparatively inexpensive, investments there could make Yale an undisputed leader. Instead, he said, the University appears to be splitting funds across a number of expensive disciplines with its science initiatives, according to Yale’s University Science Strategy Committee report.

Eire said that hiring has been an issue for the History Department in recent years. He explained that some of the History Department’s tenured professors are nearing retirement or have left for other institutions. Additionally, the number of new hires has not proportionally kept up with the rise in the student population. The administration has denied about a quarter of the department’s requests for slots to conduct faculty searches in recent years, he said.

Generally, Eire said, the humanities — where Yale has traditionally made its name — are being demoted in favor of sciences and social sciences. In the past 10 years, the number of students majoring in the arts and humanities has declined from 529 to 357, while the number of students majoring in the physical sciences and engineering has grown from about 137 to 317.

“I do worry that the historical strength in the Humanities at Yale is weakening,” Kastan wrote in an email to the News. “In every statement of University priorities, most recently in President Salovey’s letter of October 13, the arts and humanities are inevitably buried at the end, after some lengthy and enthusiastic description of major investments in the sciences and engineering, which always now occupy the ‘five ideas for top-priority investment,’ as a 2018 report had it.”

A report released by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Senate last year noted that many faculty members thought their departments were no longer among the highest-ranked in the country and feared the University was too cautious in its spending on Yale College.

FAS Dean of Humanities Kathryn Lofton said that Yale’s humanities programs have never been stronger and that there is no university in the nation that has invested as many resources as Yale has in sustaining the humanities. For example, Lofton said, the University is set to open this year a new building for the humanities, called the Humanities Quadrangle, at the site of the old Hall of Graduate Studies.

But Kastan said there is widespread confusion over what the new humanities building is meant for. He said the confusion represents a larger issue — that people may not know how the humanities are useful when humanities skills are not as marketable as training in the sciences.

At universities across the country, including Yale, the humanities are increasingly considered a luxury, Eire said. Kastan added that people may feel the arts and humanities are nonessential, and therefore areas that Yale both metaphorically and literally cannot afford.

“There are, of course, serious global challenges that programs in science and engineering are needed to address,” Kastan wrote. “But there are other challenges that we face. It has never been clearer that truth matters, and justice, freedom, beauty, and love. … The wonderful thing about the humanities is that its subject matter and the qualities needed to study it are of equal value, which is in fact priceless.”

Rose Horowitch | rose.horowitch@yale.edu