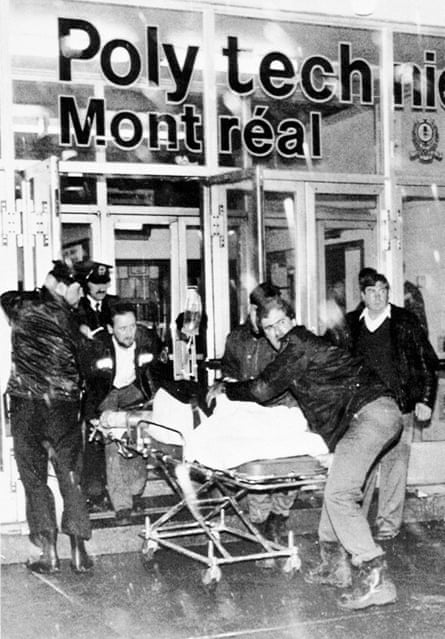

Late in the afternoon on 6 December 1989, a young man walked into Montreal’s Polytechnique engineering school with a semi-automatic rifle and killed 14 women, injured 14 others (including four men), then killed himself.

Marc Lépine’s page-long suicide note, written in French, made his motivations clear: “Feminists have always enraged me,” he wrote. “I have decided to send the feminists, who have always ruined my life, to their Maker.”

In Canada, 6 December is now a national day of remembrance and action on violence against women.

But the events of three decades ago are not a horrifying memory safely confined to a bygone era. From the viewpoint of 2019, the Polytechnique shooting now seems like an unfortunate foretelling of things to come.

Two weeks ago, a young woman in Chicago was killed by a man after she ignored his catcalls. Last November, a man whose hatred of women was well-documented online shot six women at a hot yoga studio, killing two. And seven months earlier, a man named Alek Minassian drove a van on to a Toronto sidewalk and killed 10 people, eight of them women.

The sexually frustrated young man behind the van’s wheel – a self-described incel, or “involuntary celibate” – saw his act as retribution against women who had starved him of the affection he felt he was rightfully owed. Minassian said he was inspired by Elliot Rodger, an incel and wannabe pickup artist who shot 20 people in 2014.

“I think the link between Polytechnique and the van attack is so clear, so direct, so obvious,” said Julie Lalonde, a Canadian educator focused on violence against women. The link is more than a virulent hatred of women – it is also the ability for misogynists and antifeminists to find support for that hatred in both fringe groups and in mainstream culture.

Finding that support is easier now than it’s ever been.

The pseudonymous “Liz” (a volunteer researcher on hate groups in Canada who “outs” extremists – and who uses a fake name because of the volume of violent threats her alter ego receives) says misogyny is a powerful undercurrent in all alt-right and white supremacist online groups.

“Where do you really start to discuss the intersection between misogyny and hate groups, when they are really one and the same?” asked Liz, adding that hatred of women often serves as a base upon which to build other forms of hate.

“The fact that [misogyny] acts as such a pipeline makes the incel movement exceptionally dangerous,” Liz continued. “I think that’s actually an aspect that people overlook; people look at it as kind of insular, like it’s in a vacuum – ‘Oh, they just hate women.’ But hate is infectious. When you learn to hate, you learn to hate more, and more, and more. It’s a drug.”

When Lépine began composing his ideology back in the 1980s, he didn’t have an internet commiseration machine; in his suicide note, he said it took him seven years to form his extremist views. Those views ultimately ended in a mass shooting and a meticulously assembled hitlist of 19 accomplished women he would have killed if not for a “lack of time”.

Lépine targeted Polytechnique specifically because the women there were pursuing careers in engineering – a discipline he believed should be reserved for men.

Nathalie Provost was 23 when Lépine shot her. Four bullets from his legally obtained rifle entered her body and changed her life forever.

Lépine had entered her classroom and sent the 50 men and nine women to opposite sides of the room. Then he ordered the men to leave.

“He told us that we were there because he was against feminists,” she told the Guardian. “I answered back, ‘We are not feminists. We are just engineering students, and if you want to study at Polytechnique you just have to apply and you’ll be welcomed.’ And then he shot.” Six of the nine women in that room were killed.

Provost believes the same forces that radicalised the Polytechnique shooter were at work with Minassian and Alexandre Bissonnette, the young man who killed six people inside a Quebec City mosque in 2017. Both young men were radicalised online in communities that legitimized their hatred; in Bissonnette’s case, his online search history revealed he had researched feminism before deciding to kill Muslims.

A woman or girl is killed every 2.5 days in Canada, yet the issue went unaddressed during the country’s 2019 federal election. Lalonde and Mélissa Blais, a Montreal university professor and expert on the Polytechnique shooting, both say that a major obstacle to solving the issue is a widespread unwillingness to call violence against women what it is: an act of hatred.

“Marc Lépine was not the last of the dinosaurs; it’s the opposite. It’s worrying. We absolutely need to renew our view of current forms of antifeminism, and to be able to speak about it without being afraid,” said Blais.

That’s why she campaigned to have the city change a commemorative plaque hanging outside of a Montreal park honouring the women killed at Polytechnique. Instead of ambiguously reminding visitors to contemplate the “victims of the Polytechnique tragedy”, the brand-new sign speaks in no uncertain terms: “This park is named in the memory of 14 women assassinated in an antifeminist attack.”

For Blais and Liz, it’s critical to recognize that misogyny and antifeminism are often not ends in themselves, but rather strings that people can follow to the most extreme, violent forms of hatred.

And there’s no doubt that if Lépine existed at the same time as online hate groups and YouTube extremism, he would have used the internet to feed and shape his ideology and plan the shooting, said Liz. “The only difference now is that he would have live-streamed it.”