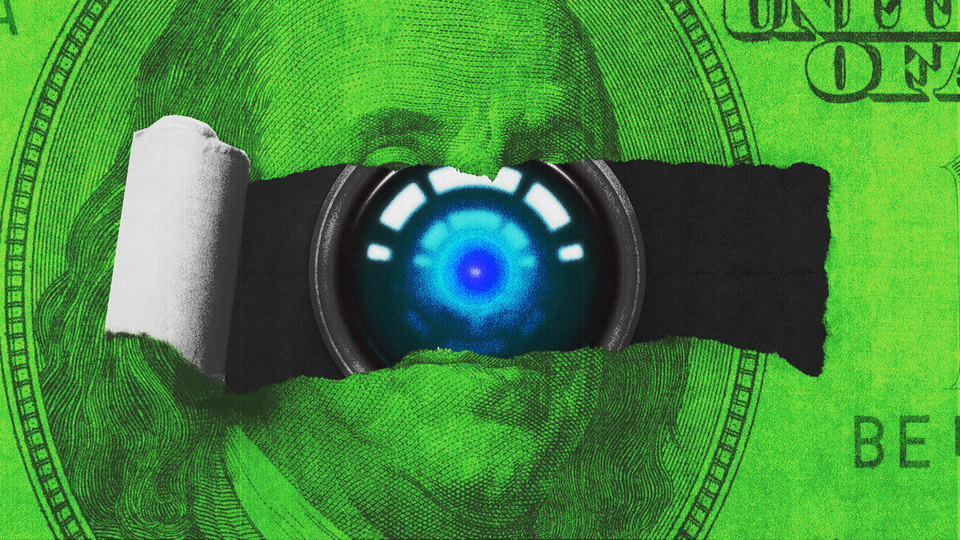

Money Will Kill ChatGPT’s Magic

Buzzy products like ChatGPT and DALL-E 2 will have to turn a profit eventually.

Arthur C. Clarke once remarked, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” That ambient sense of magic has been missing from the past decade of internet history. The advances have slowed. Each new tablet and smartphone is only a modest improvement over its predecessor. The expected revolutions—the metaverse, blockchain, self-driving cars—have plodded along, always with promises that the real transformation is just a few years away.

The one exception this year has been in the field of generative AI. After years of seemingly false promises, AI got startlingly good in 2022. It began with the AI image generators DALL-E 2, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion. Overnight, people started sharing AI artwork they had generated for free by simply typing a prompt into a text box. Some of it was weird, some was trite, and some was shockingly good. All of it was unmistakably new terrain.

That sense of wonderment accelerated last month with the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. It’s not the first AI chatbot, and it certainly won’t be the last, but its intuitive user interface and overall effectiveness leave the collective impression that the future is arriving. Professors are warning that this will be the end of the college essay. Twitter users (in a brief respite from talking about Elon Musk) are sharing delightful examples of genuinely clever writing. A common refrain: “It was like magic.”

ChatGPT is free, for now. But OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman has warned that the gravy train will eventually come to a screeching halt: “We will have to monetize it somehow at some point; the compute costs are eye-watering,” he tweeted. The company, which expects to make $200 million in 2023, is not a charity. Although OpenAI launched as a nonprofit in 2015, it jettisoned that status slightly more than three years later, instead setting up a “capped profit” research lab that is overseen by a nonprofit board. (OpenAI’s backers have agreed to make no more than 100 times what they put into the company—a mere pittance if you expect its products to one day take over the entire global economy.) Microsoft has already poured $1 billion into the company. You can just imagine a high-octane Clippy powered by ChatGPT.

Making the first taste free, so to speak, has been a brilliant marketing strategy. In the weeks since its release, more than a million users have reportedly given ChatGPT a whirl, with OpenAI footing the bill. And between the spring 2022 release of DALL-E 2, the current attention on ChatGPT, and the astonished whispers about GPT-4, an even more advanced text-based AI program supposedly arriving next year, OpenAI is well on its way to becoming the company most associated with shocking advances in consumer-facing AI. What Netflix is to streaming video and Google is to search, OpenAI might become for deep learning.

How will the use of these tools change as they become profit generators instead of loss leaders? Will they become paid-subscription products? Will they run advertisements? Will they power new companies that undercut existing industries at lower costs?

We can draw some lessons from the trajectory of the early web. I teach a course called “History of the Digital Future.” Every semester, I show my students the 1990 film Hyperland. Written by and starring Douglas Adams, the beloved author of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series, it’s billed as a “fantasy documentary”—a tour through the supposed future that was being created by multimedia technologists back then. It offers a window through time, a glimpse into what the digital future looked like during the prehistory of the web. It’s really quite fun.

The technologists of 1990 were focused on a set of radical new tools that were on the verge of upending media and education. The era of “linear, noninteractive television … the sort of television that just happens at you, that you just sit in front of like a couch potato,” as the film puts it, was coming to an end. It was about to be replaced by “software agents” (represented delightfully by Tom Baker in the film). These agents would be, in effect, robot butlers: fully customizable and interactive, personalizing your news and entertainment experiences, and entirely tailored to your interests. (Sound familiar?)

Squint, and you can make out the hazy outline of the present in this imagined digital future. We still have linear, noninteractive television, of course, but the software agents of 1990 sound a lot like the algorithmic-recommendation engines and news feeds that define our digital experience today.

The crucial difference, though, is whom the “butlers” serve in reality. Early software agents were meant to be controlled and customized by each of us, personally. Today’s algorithms are optimized to the needs and interests of the companies that develop and deploy them. Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok all algorithmically attempt to increase the amount of time you spend on their site. They are designed to serve the interests of the platform, not the public. The result, as the Atlantic executive editor Adrienne LaFrance put it, is a modern web whose architecture resembles a doomsday machine.

In retrospect, this trajectory seems obvious. Of course the software agents serve the companies rather than the consumers. There is money in serving ads against pageviews. There isn’t much money in personalized search, delight, and discovery. These technologies may develop in research-and-development labs, but they flourish or fail as capitalist enterprises. Industries, over time, build toward where the money is.

The future of generative AI might seem like uncharted terrain, but it’s really more like a hiking trail that has fallen into disrepair over the years. The path is poorly marked but well trodden: The future of this technology will run parallel to the future of Hyperland’s software agents. Bluntly put, we are going to inhabit the future that offers the most significant returns to investors. It’s best to stop imagining what a tool such as ChatGPT might accomplish if freely and universally deployed—as it is currently but won’t be forever, Altman has suggested—and instead start asking what potential uses will maximize revenues.

New markets materialize over time. Google, for instance, revolutionized web search in 1998. (Google Search, in its time, was magic.) There wasn’t serious money in dominating web search back then, though: The technology first needed to become effective enough to hook people. As that happened, Google launched its targeted-advertising platform, AdWords, in 2001, and became one of the most profitable companies in history over the following years. Search was not a big business, and then it was.

This is the spot where generative-AI hype seems to come most unmoored from reality. If history is any guide, the impact of tools such as ChatGPT will mostly reverberate within existing industries rather than disrupt them through direct competition. The long-term trend has been that new technologies tend to exacerbate precarity. Large, profitable industries typically ward off new entrants until they incorporate emerging technologies into their existing workflows.

We’ve been down this road before. In 1993, Michael Crichton declared that The New York Times would be dead and buried within a decade, replaced by software agents that would deliver timely, relevant, personalized news to customers eager to pay for such content. In the late 2000s, massive open online courses were supposed to be a harbinger of the death of higher education. Why pay for college when you could take online exams and earn a certificate for watching MIT professors give lectures through your laptop?

The reason technologists so often declare the imminent disruption of health care and medicine and education is not that these industries are particularly vulnerable to new technologies. It is that they are such large sectors of the economy. DALL-E 2 might be a wrecking ball aimed at freelance graphic designers, but that’s because the industry is too small and disorganized to defend itself. The American Bar Association and the health-care industry are much more effective at setting up barriers to entry. ChatGPT won’t be the end of college; it could be the end of the college-essays-for-hire business, though. It won’t be the end of The New York Times, but it might be yet another impediment to rebuilding local news. And professions made up of freelancers stringing together piecework may find themselves in serious trouble. A simple rule of thumb: The more precarious the industry, the greater the risk of disruption.

Altman himself has produced some of the most fantastical rhetoric in this category. In a 2021 essay, “Moore’s Law for Everything,” Altman envisioned a near future in which the health-care and legal professions are replaced by AI tools: “In the next five years, computer programs that can think will read legal documents and give medical advice … We can imagine AI doctors that can diagnose health problems better than any human, and AI teachers that can diagnose and explain exactly what a student doesn’t understand.”

Indeed, these promises sound remarkably similar to the public excitement surrounding IBM’s Watson computer system more than a decade ago. In 2011, Watson beat Ken Jennings at Jeopardy, setting off a wave of enthusiastic speculation that the new age of “Big Data” had arrived. Watson was hailed as a sign of broad social transformation, with radical implications for health care, finance, academia, and law. But the business case never quite came together. A decade later, The New York Times reported that Watson had been quietly repurposed for much more modest ends.

The trouble with Altman’s vision is that even if a computer program could give accurate medical advice, it still wouldn’t be able to prescribe medication, order a radiological exam, or submit paperwork that persuades insurers to cover expenses. The cost of health care in America is not directly driven by the salary of medical doctors. (Likewise, the cost of higher education has skyrocketed for decades, but believe me, this is not driven by professor pay increases.)

As a guiding example, consider what generative AI could mean for the public-relations industry. Let’s assume for a moment that either now or very soon, programs like ChatGPT will be able to provide average advertising copy at a fraction of existing costs. ChatGPT’s greatest strength is its ability to generate clichés: It can, with just a little coaxing, figure out what words are frequently grouped together. The majority of marketing materials are utterly predictable, perfectly suited to a program like ChatGPT—just try asking it for a few lines about the whitening properties of toothpaste.

This sounds like an industry-wide cataclysm. But I suspect that the impacts will be modest, because there’s a hurdle for adoption: Which executives will choose to communicate to their board and shareholders that a great cost-saving measure would be to put a neural net in charge of the company’s advertising efforts? ChatGPT will much more likely be incorporated into existing companies. PR firms will be able to employ fewer people and charge the same rates by adding GPT-type tools into their production processes. Change will be slow in this industry precisely because of existing institutional arrangements that induce friction by design.

Then there are the unanswered questions about how regulations, old and new, will influence the development of generative AI. Napster was poised to be an industry-killer, completely transforming music, until the lawyers got involved. Twitter users are already posting generative-AI images of Mickey Mouse holding a machine gun. Someone is going to lose when the lawyers and regulators step in. It probably won’t be Disney.

Institutions, over time, adapt to new technologies. New technologies are incorporated into large, complex social systems. Every revolutionary new technology changes and is changed by the existing social system; it is not an immutable force of nature. The shape of these revenue models will not be clear for years, and we collectively have the agency to influence how it develops. That, ultimately, is where our attention ought to lie. The thing about magic acts is that they always involve some sleight of hand.