What the Veneration of Gandhi’s Killer Says About India

Imagine Americans putting up statues of the man who shot Lincoln. The equivalent is happening in India today.

Imagine an America in the not-so-distant future. A right-wing populist politician has just been reelected president of the United States, stirring a wave of ethnonationalism not seen since the Trump presidency. Amid the country’s nativist turn, a cult of personality forms around John Wilkes Booth, the actor who fatally shot President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre just days after the end of the Civil War. Members of the president’s party hail Booth as a champion of the Confederate cause. Statues and memorials are erected in his honor. Although the president still pays lip service to Lincoln and his legacy, he is politically aligned much more closely with Booth.

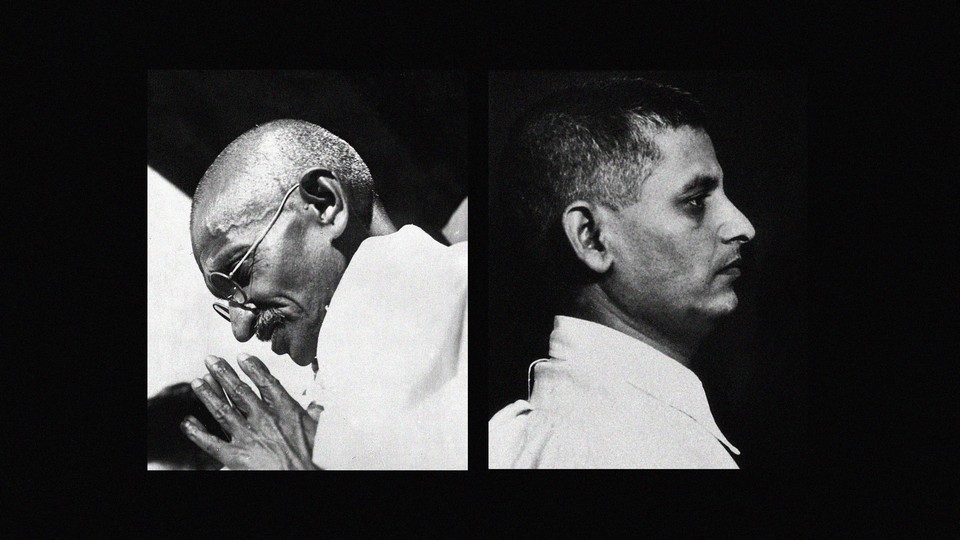

In the United States, this is a futurological fantasy, but in India a similar scenario is a reality: The man who assassinated Mahatma Gandhi, the father of India’s independence movement and the country’s most revered figure, is celebrated today—by some, at least—as a national hero. Nathuram Godse, who shot Gandhi to death on January 30, 1948, and was hanged the following year, has been hailed by Hindu nationalists, including some members of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), as a martyr and a patriot. Statues and memorials have been erected in his honor. Even Godse’s birthday, May 19, is celebrated by groups such as the right-wing political party Hindu Mahasabha as a kind of holy day.

This year, that day happened to fall on the press night for The Father and the Assassin, a new play at the National Theatre in London about the life of Godse by the Indian playwright Anupama Chandrasekhar. That a show about the man who killed Gandhi would open today in an international city speaks to the transformation of a figure once reviled, if even remembered, into an ascendant avatar of Hindu nationalism and its hold over present-day India.

Godse subscribed to the teachings of the Indian politician and political activist Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, whose Hindutva ideology articulated an Indian identity inextricably tied to the Hindu faith. Godse was also a member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a Hindu-nationalist paramilitary organization founded in 1925 that seeks the creation of a Hindu rashtra, or “nation.” This idea of India posed a direct challenge to the secular and inclusive vision of the country championed by Gandhi and India’s other founding fathers. Godse believed that Gandhi had betrayed Hindus by acquiescing to the partition of India (which led to the creation of Muslim-majority Pakistan) and acceding to Muslim demands.

“Once you get to know my story,” says Shubham Saraf in the role of Godse at the National Theatre, “then you’ll understand me.” In a larger perspective, to understand Godse’s reputation today is to get to know India itself, and see how it has changed.

The lionization of Godse in India today would have been unthinkable just a few decades ago. In the aftermath of Gandhi’s assassination, Godse and his co-conspirators were condemned as traitors. The organizations with which Godse was affiliated were vilified and, in the case of the RSS, even temporarily banned. “The cause for which he stood suddenly became discredited,” Kapil Komireddi, the author of Malevolent Republic: A Short History of the New India, told me. By killing the nation’s Bapu, or “father,” “Godse was perceived as an evil and a monster,” he said.

This toxicity would stick into the 1980s, when the RSS’s political wing, the now-ruling BJP, was formed. Until that point, “no respectable Indian wanted to touch the RSS,” Audrey Truschke, a historian of South Asia at Rutgers University, told me. But as the BJP became more popular, Hindu-nationalist policies slowly began creeping back into currency, culminating in the election of Modi in 2014. While Modi continues to pay tribute to Gandhi, whose legacy still holds enormous soft power in India and around the world, Modi’s Hindu-nationalist policies and worldview are more in tune with Godse’s.

“You will always remain a footnote,” one of the prison guards goads Godse in the play, as he awaits trial for Gandhi’s murder. Footnote no more: The rehabilitation of Godse is now visible across the country in the form of statues, temples, and memorials. The Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, which is governed by the BJP, even made a bid to rename the city of Meerut after Godse (though it ultimately failed).

What little is known about Gandhi’s killer, however, suggests that the Hindu-nationalist symbol he has become bears little resemblance to the man he actually was. Chandrasekhar wrote Godse in The Father and the Assassin as neither an ideologue like Savarkar nor a political giant like Gandhi. Rather, Godse emerges as an impressionable young man questing for a sense of purpose in a country undergoing immense change. He eventually found that calling in an ideology of jingoism and hate, which the play suggests was rooted in a phobia about being seen as weak or effeminate because his parents had initially raised him as a girl, fearing that he would otherwise share the fate of three older male siblings who had died in infancy.

Today, Godse “is presented as a nationalist, as someone who was very much concerned about Hindu interests, but the reality was completely different,” Dhirendra K. Jha, the author of Gandhi’s Assassin: The Making of Nathuram Godse and His Idea of India, told me. Far from being deeply religious or patriotic, Jha argued, Godse was loyal only to the RSS and its extremist aims. The group did not repay his loyalty after the assassination—attempting to distance itself by claiming that Godse was no longer a member. Even Godse adopted this party line, though Jha said that archival records tell a different story. The disgrace and disavowals seem a long way from India today, where some BJP politicians have gone out of their way to express their admiration for Godse.

The question of Nathuram Godse’s real identity is, in a sense, irrelevant. As with most political symbols, their utility has little to do with how closely they cleave to historical accuracy. “The appeal of Godse doesn’t rely so much on Godse,” Komireddi said. “The appeal of Godse really rests in the appeal of Modi and the kind of country India is becoming.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.