Cancel Culture Isn’t the Real Threat to Academic Freedom

Like any other institution, the academy is embedded in the power relations of a society.

The woman in the video is about the same age as my mother. She is speaking at a school-board meeting in Virginia as a concerned parent.

“I’ve been very alarmed by what’s going on in our schools,” she reads from prepared notes. “You are now teaching, training our children to be social-justice warriors and to loathe our country and our history.” Her voice is soft but stern. She recounts her youth in Mao Zedong’s China and the political fanaticism she witnessed firsthand, before calling critical race theory “the American version of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.” At the end of her remarks, the audience bursts into cheers. “Virginia Mom Who Survived Maoist China Eviscerates School Board’s Critical Race Theory Push,” blares the headline on Fox News.

As a Chinese academic working in the U.S., I watched the video and was disconcerted by its familiarity. The speaker’s views are not uncommon among many first-generation Chinese immigrants, who are grateful to their new country and eager to assimilate. Critical race theory, the analytical framework developed by a small group of legal scholars to address structural racism, has been morphed into a derogatory term by the right. The loudest conservative voices reject any effort to talk about racial inequality as divisive and dangerous, akin to the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s mass movement that plunged China into a decade of turmoil and claimed more than a million lives.

At a time when authorities in Beijing have tightened their grip at home and are extending their reach abroad, when U.S.-China relations have tumbled to the lowest point in decades, and when students and scholars of Chinese descent face heightened scrutiny, the frequent invocation of my birth country in the discourse on free expression is not random or simply misguided: It’s a product and a tool of geopolitics. China has become a foil, the embodiment of authoritarian evil eroding American freedom.

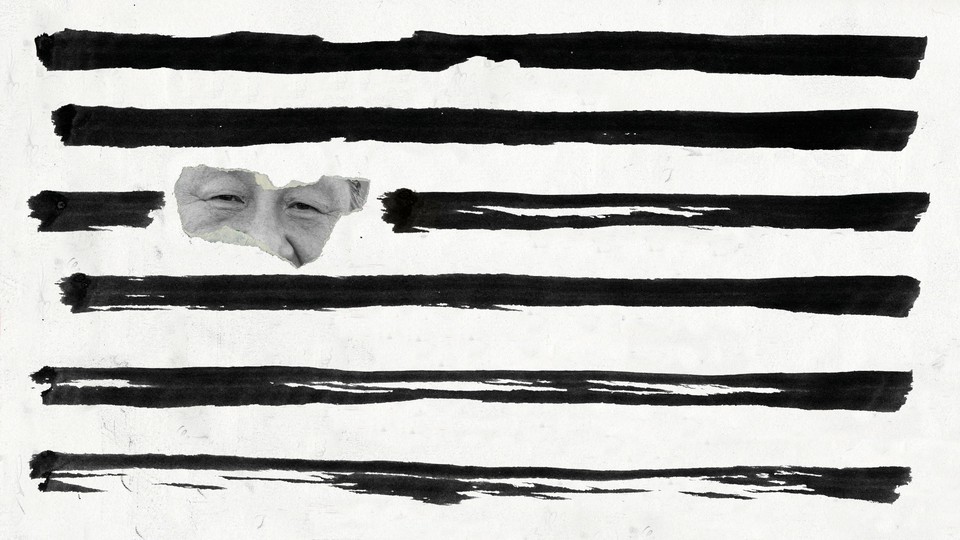

The use of the Cultural Revolution to characterize the state of free speech on American campuses reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of Chinese history and American society. Academic freedom is in peril. Focusing the blame on “cancel culture” or “social-justice warriors,” however, would be to miss the greater challenge. The root of the problem lies not in zealous individuals or foreign interference—it’s always easier to focus on incidents than to examine the system, to blame the other than to reckon with the self—but in relations of power that bend institutions to the will of the powerful.

Growing up in China, I was taught at a very young age that the two biggest taboos were politics and death. When I moved to the U.S. in 2009 for graduate school, I proudly declared to my family that I was leaving not just to pursue a degree but “to live in a free country.” One of the first things I did after arriving at the University of Chicago was type the words Tiananmen and 1989 into Google. I had sensed the presence of a seismic event in my birth year by tracing the contours of censorship—a date that cannot be mentioned, heightened surveillance around its anniversary, and my mother's refusal to answer any questions about it—but only in a foreign land was I able to reach the forbidden history and learn what my government had denied me.

I was eager to exercise my newly gained freedoms and participate in American democracy, however limited opportunities are for an international student. I could not vote, donate to a candidate, or run for office, so I volunteered at a phone bank for Barack Obama’s reelection campaign and pressed questions to local candidates. When the Institute of Politics opened at the University of Chicago in 2013, I was among the organization’s first student leaders. By facilitating many of its events, I watched debates on free expression unfold: How should a university respond to offensive speech? Are trigger warnings necessary? Should the campus be a “safe space”? In 2014, the university released the Report on the Committee of Free Expression, which has become known as the Chicago Principles, reaffirming its commitment to “free, robust, and uninhibited debate.” In conversations with schoolmates, I defended the principles and used my upbringing in an authoritarian society to lecture my American friends, whom I saw as well-meaning but overly sensitive, spoiled by the rights they took for granted and blind to the dangers of ideological control.

In retrospect, I recognize the limits of my argument. By upholding free speech as a shield and dismissing grievances over the sometimes ill-conceived tactics of the aggrieved, such as shouting down a speaker, I was the one reluctant to receive new ideas, to understand why certain speech offends and how shifting norms around race, gender, and sexuality echo the deep wells of discrimination, the progresses made, and the long roads ahead. Still new to this country, I clung to an idealized version of the U.S. not because of what it is but because of what I needed it to be to justify my journey.

My awakening came in 2016, as the ugly truths of this nation were laid bare. The banner of “free expression” was hijacked by the far-right and its sympathizers, whose concept of an open-minded campus was measured by the most bigoted speaker it was willing to host. With a spike in hate crimes and waves of discriminatory policies, the marginalized were not fragile for pointing out the dangers to their being. As racism, misogyny, and xenophobia occupied the highest levels of government, these harmful ideas did not need the additional platform of a university event to be heard, nor could they be defeated by a mere exchange of words. What the most vocal proponents of “campus free speech” desired was not the freedom of inquiry but a license to offend, free from consequences.

Earlier this year, the Hong Kong prodemocracy activist Nathan Law was invited to speak at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy. The Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA) at my alma mater emailed the deans of the Harris School to express “grave concerns” that the invitation of Law fell “outside the purviews of free speech” and was “extremely hurtful, insulting and angering” to the Chinese student community.

Law’s event at the Harris School proceeded as planned, but his talks at other U.S. campuses faced similar opposition. “HK activists’ free speech are threatened by pro-CCP (Chinese Communist Party) nationalists, such as CSSAs, which are CCP’s extended arms,” Law wrote on Twitter.

The long arm of the Chinese state does indeed pose serious threats to academic freedom, but the main risk is not from nationalistic students. CSSA members are diverse in political opinion, though the ones supportive of Beijing’s policies are usually the most vocal. The few who surveil or harass other members of the campus community should face discipline, but painting every Chinese student who holds pro-government views as a potential agent of Beijing erases individual agency and feeds racist paranoia. Students, however misinformed, are also entitled to free expression and, hopefully, will learn and correct their mistakes.

The vulnerability instead lies in the operational model of the university. With the privatization and commercialization of higher education, universities are run like businesses, in which a degree becomes a product, students become customers, and the world’s most populous country becomes the biggest overseas market. Numbering nearly 400,000 before the coronavirus pandemic, Chinese students make up more than a third of U.S. universities’ international student population. Schools are often underprepared for the influx of Chinese students, making them rely on organizations like CSSAs, which keep a cozy relationship with Chinese consulates but also provide services and a sense of community for overseas students.

The financial incentives from tuition income and other lucrative collaborations with Chinese entities have also exposed schools to Chinese-state pressure and downturns in bilateral relations. In 2017, the Chinese government cut funding for visiting scholars to the University of California at San Diego after the Dalai Lama gave the institution’s commencement speech. As tensions rose between Washington and Beijing, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, home to the largest Chinese-student community in the U.S., took out a $61 million insurance policy against a potential drop in Chinese enrollment. Academic publishers including Cambridge University Press and Springer Nature have capitulated to Beijing’s censorship demands and blocked content for the Chinese market. Emblematic of both the power and the limitations of the academic community, Cambridge reversed its decision after widespread protests and threats of a boycott; Springer did not.

Over the past few years, there has been a growing awareness of Beijing’s influence on U.S. campuses, but the problem is routinely portrayed as uniquely “Chinese.” The blame is assigned to an external actor, and the solution is to impose a border—on money, ideas, and personnel. This amounts to little more than swapping one source of state pressure (foreign) for another (domestic). Protecting American universities from the “China threat” has become another lever in Washington’s tool kit, and jingoistic rhetoric fans xenophobia and racial animosity.

There are few better examples of a genuine challenge to academic freedom being misappropriated by geopolitics than the controversy around Confucius Institutes. Launched in 2004 by China’s Ministry of Education, the centers are located at colleges and universities around the world and offer lessons on Chinese language and culture. They are jointly financed and managed by Beijing and host institutions. Though the latter have varying degrees of autonomy, the Chinese government provides the candidate pool of teachers, preapproves much of the course material, and retains the right to terminate a contract in case of action that “severely harms the image or reputation” of the program.

In 2014, the American Association of University Professors and its Canadian counterpart issued a report criticizing Confucius Institutes for allowing third-party control of academic matters. That September, the University of Chicago ended its partnership with the program, after faculty and students petitioned for the closure on academic-freedom grounds. It was the first institution in the U.S. to do so. Few others followed at the time. Concerns over Confucius Institutes were notably separate from discourse on campus free expression and, initially, were largely ignored by school administrators. Existing centers continued and new ones opened, totaling more than 100 in the U.S. by 2017.

The figure has plummeted to only 36 this fall; at least eight more are scheduled to close. The pressure came not from the academy but from the U.S. government. Amid escalating rivalry between the U.S. and China, legitimate questions about censorship and self-censorship at these language centers have been swept up in a frenzied narrative of indoctrination and espionage. The focus has shifted from academic freedom to national security. Lawmakers call on schools in their districts to shut down Confucius Institutes. The National Defense Authorization Act prohibits universities that host these centers from receiving Department of Defense funding. As universities acquiesce to these demands, the future of Chinese-language learning remains uncertain. Flawed as they are, Confucius Institutes have fulfilled a genuine need, especially at smaller schools with fewer resources.

Discussions on this topic are incomplete without reflecting on the history and politics of foreign-language education, which has long been a low priority for state and federal governments except in moments of national emergency. Language skills are valued largely for their usefulness to the state, to advance foreign-policy agendas or improve economic productivity. In 1958, shortly after the launch of Sputnik 1, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act, which established federal support for foreign-language training. The law included a loyalty oath to the U.S. government and the Constitution as a condition of funding. Universities pushed back, boycotting the act’s student-loan program, and the loyalty provision was repealed during the Kennedy administration.

Decades later, Stewart E. McClure, the chief clerk of the Senate committee responsible for the legislation, reflected on his role in inventing the name of the law, a “God-awful title” that was politically expedient: “If there are any words less compatible, really, intellectually, in terms of what is the purpose of education—it’s not to defend the country; it’s to defend the mind and develop the human spirit, not to build cannons and battleships.”

A university is not a public square. Miss the institutional context, and the understanding of academic freedom is flattened to an individual's right to free expression. Buried in the latest controversy over a disinvited speaker or a poorly worded email, the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia has voted to effectively end tenure in the state’s public-university system. Donors have swayed hiring decisions at the University of North Carolina and tried to shape the curriculum at Yale. To the drumbeat of strategic rivalry, the State Department has placed various restrictions on Chinese students and researchers, the Justice Department is carrying out a “China Initiative” to combat economic espionage with a focus on academia, and funding for science, according to bills in Congress, is aimed at winning the competition against China. As a backlash to last year’s protests for racial justice and as a prelude to the next election cycle, more than two dozen states have introduced bills or passed laws that ban critical race theory at schools and limit teaching on racism and gender discrimination.

I do not know whether proponents of these bans realize how much their position resembles that of Beijing and its followers, the red menace they rail against. An honest history lesson would reveal systemic oppression and implicate the powerful. The language of unity and national pride is weaponized to absolve the authorities and conceal the truth.

An ivory tower above and beyond the messy planes of politics is an illusion. The academy is not an abstraction. It has a history and depends on a set of material conditions to function. It’s not merely a meeting of minds but also a congregation of bodies, in a world where some bodies are valued more than others. Like any other institution, the academy is embedded in the power relations of a society, and relations of power, if not actively contested, are always reproduced. Regarding racist speech and critiques of racist speech as equal in a “marketplace of ideas” is not being neutral; it is perpetuating racism. Too often, discussions on “campus free speech” are distracted by superficial optics and overlook the underlying power dynamic. The privileged cry victim when their privilege is being challenged. The disenfranchised resort to aggressive tactics in a desperate attempt to be heard and are cast as the bully.

The solution to hateful speech is not outlawing speech; constructing and enforcing a ban yields more power to the already powerful. The path forward lies in leveling the terrains of injustice and empowering the marginalized, and that requires efforts from all of society. The academy is not an activist organization, but it has a professional duty to challenge orthodoxy and a moral obligation to speak truth to power. Academic freedom is not just freedom from pressures of the state or moneyed interests; more important, it’s the freedom to explore, to transcend boundaries, to discover new realms of knowledge and imagine new ways of being.

Since I left China, over the phone and through text messages, my mother has repeated a warning: “Focus on academics. Stay away from politics.” She was disappointed when I majored in physics; she had been hoping I would choose a more “feminine” profession, such as teaching high-school-English. She has, in any case, taken comfort in the thought that exploring the fundamental laws of nature will keep me far from the affairs of the state. I have not told her about my recent career change to research the ethics and governance of science, or the many articles I have written that are critical of the Chinese government. In the shadows of an oppressive regime, silence can be a language of love.

I reckon with the denial in my mother’s caution, a condition of enduring authoritarianism; staying away from politics means staying obedient to the state. We all inhabit political lives; the difference is between choosing passivity and exercising agency.

Every day, I go to work at one of the oldest institutions of higher learning on this continent. I’m reminded of the fact that this campus predates the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, that universities outlive kings and popes, empires and dictators. As I walk past the storied halls and gothic spires, I’m also heavy with an awareness that legacies of slavery and colonialism mark this place. For most of the institution’s history, a body like mine—foreign, female, and nonwhite—was never accepted. My presence here is a fruit of past struggles. My belonging contends the borders of the academy. My humanity is not up for debate.