Texas’s Social-Media Law Is Dangerous. Striking It Down Could Be Worse.

Beware giving Big Tech a constitutional right to avoid regulation.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

As a progressive legal scholar and activist, I never would have expected to end up on the same side as Greg Abbott, the conservative governor of Texas, in a Supreme Court dispute. But a pair of cases being argued next week have scrambled traditional ideological alliances.

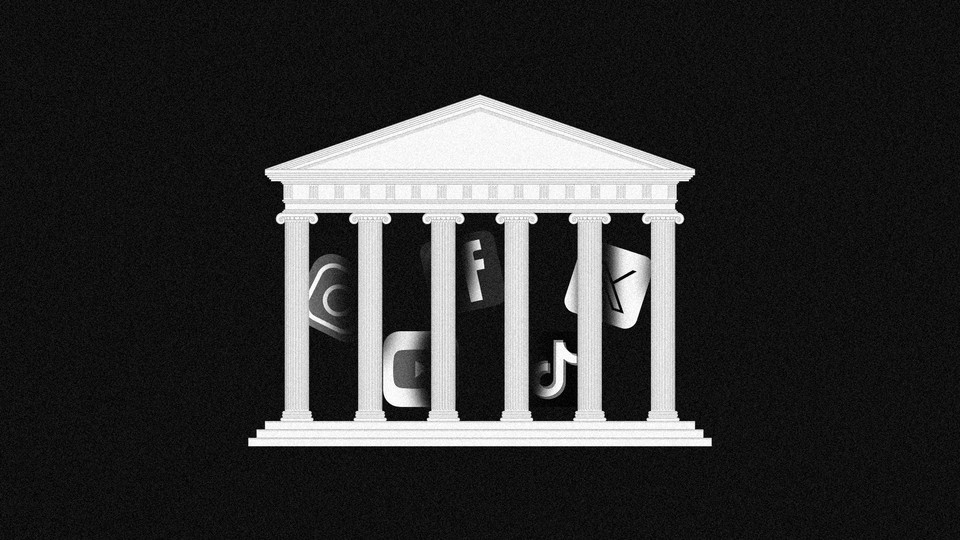

The arguments concern laws in Texas and Florida, passed in 2021, that if allowed to go into effect would largely prevent the biggest social-media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok, from moderating their content. The tech companies have challenged those laws—which stem from Republican complaints about “shadowbanning” and “censorship”—under the First Amendment, arguing that they have a constitutional right to allow, or not allow, whatever content they want. Because the laws would limit the platforms’ ability to police hate speech, conspiracy theories, and vaccine misinformation, many liberal organizations and Democratic officials have lined up to defend giant corporations that they otherwise tend to vilify. On the flip side, many conservative groups have taken a break from dismantling the administrative state to support the government’s power to regulate private businesses. Everyone’s bedfellows are strange.

I joined a group of liberal law professors who filed a brief on behalf of Texas. Many of our traditional allies think that siding with Abbott and his attorney general, Ken Paxton, is ill-advised to say the least, and I understand that. The laws in question are bad, and if upheld, will have bad consequences. But a broad constitutional ruling against them—a ruling that holds that the government cannot prohibit dominant platforms from unfairly discriminating against certain users—would be even worse.

At an abstract level, the Texas law is based on a kernel of a good idea, one with appeal across the political spectrum. Social-media platforms and search engines have tremendous power over communications and access to information. A platform’s decision to ban a certain user or prohibit a particular point of view can have a dramatic influence on public discourse and the political process. Leaving that much power in the hands of a tiny number of unregulated private entities poses serious problems in a democracy. One way America has traditionally dealt with this dynamic is through nondiscrimination laws that require powerful private entities to treat everyone fairly.

The execution, however, leaves much to be desired. Both the Texas and Florida laws were passed at a moment when many Republican lawmakers were railing against perceived anti-conservative discrimination by tech platforms. Facebook and Twitter had ousted Donald Trump after January 6. Throughout the pandemic and the run-up to the 2020 election, platforms had gotten more aggressive about banning certain types of content, including COVID misinformation and QAnon conspiracy theories. These crackdowns appeared to disproportionately affect conservative users. According to Greg Abbott and other Republican politicians, that was by design.

The laws reflect their origins in hyperbolic politics. They are sloppy and read more like propaganda than carefully considered legislation. The Texas law says that platforms can’t censor or moderate content based on viewpoint, aside from narrow carve-outs (such as child-abuse material), but it doesn’t explain how that rule is supposed to work. Within First Amendment law, the line between subject matter and viewpoint is infamously difficult to draw, and the broad wording of the Texas statute could lead to platforms abandoning content moderation entirely. (Even the bland-sounding civility requirements of a platform’s terms of service might be treated as expressing a point of view.) Similarly, the Florida law prohibits platforms from suspending the accounts of political candidates or media publications, period. This could give certain actors carte blanche to engage in potentially dangerous and abusive behavior online. Neither law deals with how algorithmic recommendation works, and how a free-for-all is likely to lead to the most toxic content being amplified.

Given these weaknesses, many experts confidently predicted that the laws would swiftly be struck down. Indeed, Florida’s was overturned by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, but the conservative Fifth Circuit upheld the Texas statute. Last year, the Supreme Court agreed to consider the constitutionality of both laws.

The plaintiff is NetChoice, the lobbying group for the social-media companies. It argues that platforms should be treated like newspapers when they moderate content. In a landmark 1974 case, the Supreme Court struck down a state law that required newspapers to allow political candidates to publish a response to critical coverage. It held that, under the First Amendment, a newspaper is exercising its First Amendment rights when it decides what to publish and what not to publish. According to NetChoice, the same logic should apply to the Instagrams and TikToks of the world. Suppressing a post or a video, it argues, is an act of “editorial discretion” protected from government regulation by the impermeable shield of the First Amendment. Just as the state can’t require outlets to publish an op-ed by a particular politician, this theory goes, it can’t force X to carry the views of both Zionists and anti-Zionists—or any other content the site doesn’t want to host.

This argument reflects a staggering degree of chutzpah, because the platforms have spent the past decade insisting that they are not like newspapers, but rather are neutral conduits that bear no responsibility for the material that appears on their services. Legally speaking, that’s true: Congress specifically decided, in 1996, to shield websites that host user-generated content from newspaper-esque liability.

But the problem with the newspaper analogy goes deeper than its opportunistic hypocrisy. Newspapers hire journalists, choose topics, and carefully express an overall editorial vision through the content they publish. They might publish submissions or letters to the editor, but they don’t simply open their pages to the public at large. A newspaper article can fairly be interpreted, on some level, as the newspaper expressing its values and priorities. To state the obvious, this is not how things work at the scale of a platform like Instagram or TikTok—values and priorities are instead expressed through algorithmic design and product infrastructure.

If newspapers are the wrong analogy, what is the right one? In its briefs, Texas argues that social-media platforms should be treated as communications infrastructure. It points to the long history of nondiscrimination laws, such as the Communications Act of 1934, that require the owners of communication networks to serve all comers equally. Your telephone provider is not allowed to censor your calls if you say something it doesn’t like, and this is not held to be a First Amendment problem. According to Texas, the same logic should apply to social-media companies.

In the brief that I co-authored, my colleagues and I propose another, less obvious analogy: shopping malls. Malls, like social-media companies, are privately owned, but as major gathering places, they play an important social and political function (or at least they used to). Accordingly, the California Supreme Court held that, under the state constitution, people had a right to “speech and petitioning, reasonably exercised, in shopping centers even when the centers are privately owned.” When a mall owner challenged that ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously rejected its argument. So long as the state isn’t imposing its own views, the Court held, it can require privately owned companies that play a public role to host speech they don’t want to host. In our brief, we argue that the same logic should apply to large social-media platforms. A law forcing platforms to publish specific messages might be unconstitutional, but not a law that merely bans viewpoint discrimination.

I am under no illusions about the Texas and Florida statutes. If these poorly written laws go into effect, harmful things may happen as a result. But I’m even more worried about a decision saying that the laws violate the First Amendment, because such a ruling, unless very narrowly crafted, could prevent us from passing good versions of nondiscrimination laws.

States should be able to require platforms, for instance, to neutrally and fairly apply their own stated terms of service. Congress should be able to prohibit platforms from discriminating against news organizations—such as by burying their content—based on their size or point of view, a requirement embedded in proposed legislation by Senator Amy Klobuchar. The alternative is to give the likes of Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk the inalienable right to censor their political opponents, if they so choose.

In fact, depending on how the Court rules, the consequences could go even further. A ruling that broadly insulates content moderation from regulation could jeopardize all kinds of efforts to regulate digital platforms. For instance, state legislatures across the country have introduced or passed bills designed to protect teenagers from the worst effects of social media. Many of them would regulate content moderation directly. Some would require platforms to mitigate harms to children; others would prohibit them from using algorithms to recommend content. NetChoice has filed briefs in courts around the country (including in Utah, California, and Arkansas) arguing that these laws violate the First Amendment. That argument has succeeded at least twice so far, including in a lawsuit temporarily blocking California’s Age-Appropriate Design Code Act from being enforced. A Supreme Court ruling for NetChoice in the pair of cases being argued next week would likely make blocking child-safety social-media bills easier just as they’re gaining momentum. That’s one of the reasons 22 attorneys general, led by New York’s Letitia James and including those of California, Connecticut, Minnesota, and the District of Columbia, filed a brief outlining their interest in preserving state authority to regulate social media.

Sometimes the solution to a bad law is to go to court. But sometimes the solution to a bad law is to pass a better one. Rather than lining up to give Meta, YouTube, X, and TikTok capacious constitutional immunity, the people who are worried about these laws should be focusing their energies on getting Congress to pass more sensible regulations instead.

Support for this project was provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.