The Quiet Courage of Bob Moses

The late civil-rights leader understood that grassroots organizing was key to delivering political power to Black Americans in the South.

In 1960, 25-year-old Bob Moses, who died over the weekend at the age of 86, arrived at the Cleveland, Mississippi, home of a World War II veteran named Amzie Moore. Moses was coming from the Atlanta offices of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). A New York City teacher, he had first traveled south to join the civil-rights movement after being inspired by the sit-ins earlier that year. But the work at SCLC was slow and tedious. It was a top-down organization, dominated by the towering figure of King and his dizzying schedule of events and initiatives. Office duties were not what Bob Moses had in mind.

Ella Baker, a veteran NAACP organizer who helped create the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) after the sit-ins, was working with Moses that summer. She understood his restlessness—which I also came to understand decades later, when I interviewed him for a book I was writing—and offered him a way to engage more directly with people instead of paper. Baker gave Moses a list of names of longtime NAACP organizers scattered across the Deep South, where the movement was less prevalent and more dangerous. In a time when belonging to the NAACP could get you evicted, fired, or even killed, the activists on that list held on to their membership.

Moses visited the people on Baker’s list. He went to Deep South cities like Talladega and Birmingham, Alabama; New Orleans and Shreveport, Louisiana; and Clarksdale, Mississippi. His most important visit of the journey was with Amzie Moore, who had also been inspired by the sit-ins and was looking for a way of “capturing this sit-in energy,” Moses remembered nearly 50 years later. The grizzled activist vetted the younger organizer, testing his mettle in front of Black Mississippians who had lived their entire life under Jim Crow and fully knew its dangers. “He put me up in front of a church,” Moses told me. “Amzie wanted to see how I related to people and presented myself and the movement.” The following year, Moses did something that a national leader like King never could have done—he brought that movement into Mississippi and in turn helped deliver Mississippi into America.

Black Mississippians had long been fighting for civil rights, but this phase of their struggle was different. Led by Moses, SNCC was determined to crack open the state that one professor had dubbed “the closed society” for its repressive government, which haunted Black people and even employed a statewide investigative unit to preserve Jim Crow. SNCC’s strategy differed from that of other civil-rights organizations in that the group wanted to develop a grassroots approach that would empower everyday Black people to directly challenge Jim Crow. This version of the movement, grounded in personal example and moral suasion, is lesser known to many people than the bridge in Selma, Alabama, or the March on Washington. But in many ways, it was much more powerful than any single event or speech.

Following his initial contact with Moore, Moses led SNCC into McComb, then Hattiesburg, and finally into the Delta, recruiting, training, and inspiring people to join them along the way. They met local Black people in churches and on front porches and slowly pieced together a powerful coalition of freedom fighters from all types of backgrounds. SNCC launched hundreds of demonstrations and brought tens of thousands of people to voting places where they attempted to register to vote. The majority were turned away by racist white registrars, but even these denials were important because Black people had to prove intent to counter arguments that they just weren’t interested in voting. The documentation of these experiences helped pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Moses and his fellow organizers fought for civil rights in exceedingly violent places, where people were killed for trivial violations of Jim Crow norms, let alone trying to overthrow the system entirely. In 1963, Moses was nearly killed himself in a drive-by shooting targeted at activists. Moore remembered Moses and his fellow SNCC activists as having “more courage than any group of people I’ve ever met.”

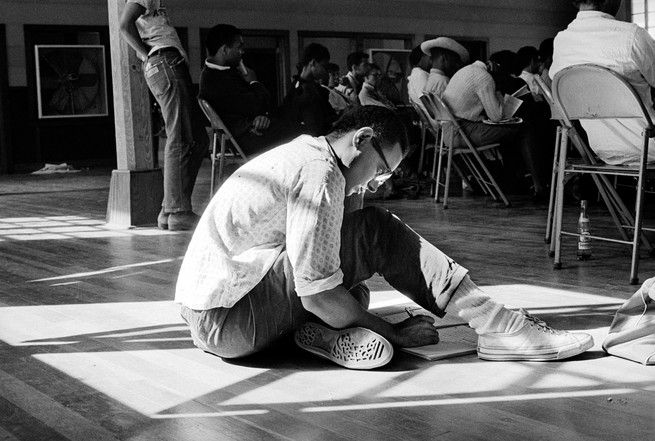

The story of Bob Moses’s civil-rights movement is not punctuated with famous letters from jails or soaring oratory on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Rather, it’s that of a quiet young man standing in a church in front of a handful of people, helping them understand their civil rights and encouraging them to face their fears and try to register to vote. Moses asked his audiences questions about their life, and he used their answers to help them mobilize. He spoke softly so that people had to hush and pay attention to hear him. He lived and ate among them, briefly threading his life into theirs as they worked together in a common struggle. He rarely donned a suit, dressing like the working-class Black people he was trying to lead. And he operated with a convincing calmness and certainty that earned him what John Lewis described as a “godlike reverence” from others in the movement.

Moses entered the darkest places in the country with the light of an idea. He believed that everyday people could change the world, and he carried an almost illogical vision of what America could be. He believed that every human mattered as much as he did, and he never asked anyone to do anything he wasn’t willing to do himself. His work occurred when the cameras weren’t looking, and his strength came not in outside recognition but inner resolve. He gave his labor and intellect with the clarity and urgency of a prophet. For those who met Moses, the movement was not merely a revolution of the country, but a revelation of the mind. Jim Crow was designed to crush the hopes and dreams of Black people. Bob Moses went into Mississippi to restore them.

Moses is perhaps most famous for helping organize the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, when hundreds of mostly white volunteers traveled to the Magnolia State to join the local struggle. He recruited people who wanted to join the civil-rights movement as servants and not heroes. “Don’t come to Mississippi this summer to save the Mississippi Negro,” John Lewis remembered Moses telling the white volunteers. “Only come if you understand, really understand, that his freedom and yours are one.”

The civil-rights movement would have happened without Bob Moses. But it wouldn’t have had the same long-term impact without the seeds he helped plant to empower people over the duration of their lives. It’s important to remember that milestone victories such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 still had to be enforced. The new laws were monumental, but they were just the beginning of a struggle that continues today. After all the cameras left in the late ’60s, it was those local people, trained and hardened in the movement, who were still fighting to ensure access to equal rights. King generated much of the rhetoric of the movement, but it was Moses who helped foster a sustainable culture of on-the-ground organizing and leadership in the Deep South. The effects of this work have rippled for decades, especially in Mississippi. By the late ’80s, the state led the nation in the number of Black elected officials.

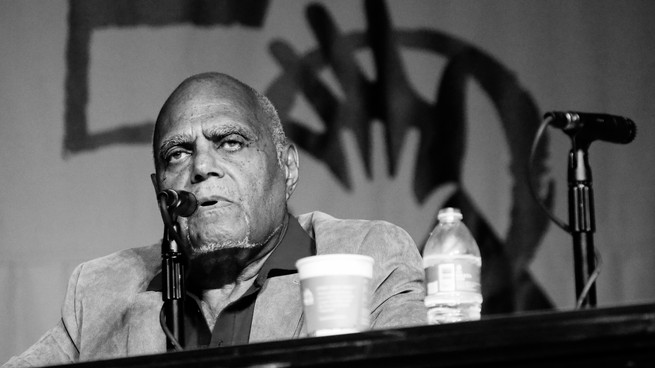

Moses left the movement in the mid-’60s, burned out by stress and the broken promises of politicians, but his activism never stopped. He lived and worked in Tanzania in the ’70s before returning to teach in the United States. In the early ’80s, he started the Algebra Project, which organized communities by using math literacy to empower underprivileged students. One of the great pleasures of my life was in 2009, when I had the opportunity to attend an Algebra Project meeting that Moses led in Mansfield, Ohio. He stood at the front of a crowded auditorium and started asking questions. The conversation began slowly and quietly, with a few smart-aleck students providing curt answers to his questions. It ended with a room full of energy and ideas about how the students’ Algebra Project could begin. As a professor and historian, I learned more about teaching and organizing during those few hours than I ever could in any archive or history book.

The legacy of Bob Moses is rooted in his brand of leadership, which might have been the most transformative idea to come out of the civil-rights movement—that everyone, even the most downtrodden, undereducated, and poor among us, deserves equality. His legacy lies somewhere in the dream space of American history, that place in our imagination where stories from the past inspire greater hope in the future. That’s where I first read about Bob Moses, back when I was a young college student struggling to understand race, years before ever meeting him in person. His courage and radical vision taught me to love America. And that’s where he’ll remain for anyone and everyone who ever dares to dream, or just needs a little push to see how they can get free.