The Cover Letter: A Short History of Every Job-Seeker's Greatest Annoyance

In the last 50 years, they've become ubiquitous. It's only now that some companies are realizing that the cover letter is more of a performance than a useful projection.

Leonardo da Vinci created some of the most resonant objects of our time -- the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper, the giant crossbow -- but perhaps his most inescapable legacy, the invention you might come across every few weeks, is the résumé. According to legend, da Vinci is said to have created the first CV when applying for a job from the Duke of Milan.

Five hundred years later, his invention is the currency of human resources departments and the bane of many job prospects. But it is nothing compared to the other half of the white-collar-job application: the cover letter.

Never quite defined, but always somehow crucial, the cover letter is now the subject of both anxiety and punditry. A recent opinion from an employer in Slate summarized the cover letter’s preeminence: “If I hate a cover letter, I won’t even look at a résumé.” But there is also evidence that cover letters are nothing but adornments. A survey conducted by reCareered found that 90% of hiring contacts surveyed simply ignored every cover letter sent to them.

Da Vinci’s invention is durable because it is so practical. Understanding a prospective employee’s past is a reasonable way to predict his or her future success. But the purpose of the cover letter is murkier. It is, ostensibly, to introduce the human being behind the accomplishments—yet, using the formal letter as the method to represent the modern applicant might obscure more than it reveals. Some employers are starting to see that and moving to alternate ways to evaluate candidates. But the vast majority of white-collar jobs still require one-page personal statements.

Where did cover letters come from, how did they become so commonplace, and why they might they be falling out of fashion after 50 years of dominance? This story begins centuries after da Vinci, in the 1930s. It’s not a cute legacy.

* * *

First, a bit of word history.

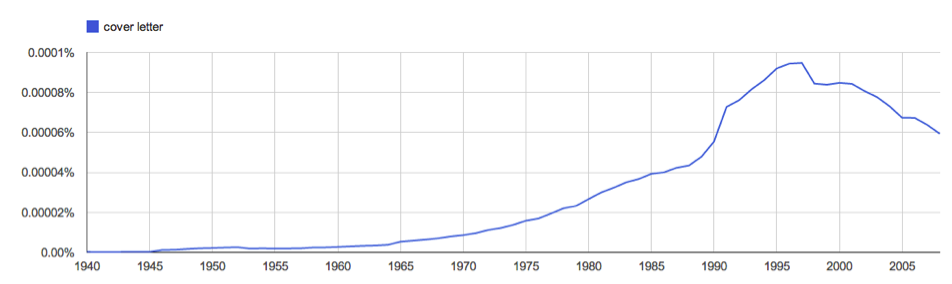

Google Ngram, an algorithm that searches the texts of Google Books, traces the rise of “cover letter” to the second half of the 20th century. The U.S. was transitioning away from manufacturing toward a service-sector economy. The percentage of white-collar jobs in the economy nearly doubled.

Why would the cover letter be appropriate for a service-sector economy? Unionized manufacturing workers were human cogs in complex systems, talented at their specific task but not required to come face-to-face with clients. It’s reasonable that the growth of services would correspond with the mainstreaming of cover letters, if their purpose is indeed to qualify the person behind the accomplishments.

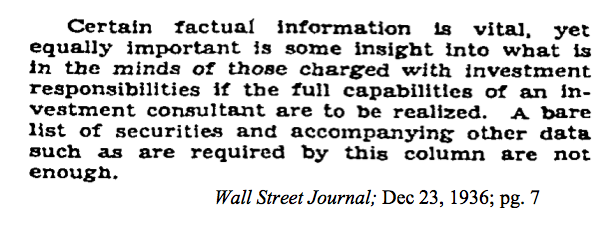

There are more clues to be found in newspaper archives—particularly as employment sources—that contain the first printed instances of “cover letters.” Starting in the 1930s, the idea of a “cover letter” became popularly used for a descriptive document that would precede some form of previously unaccompanied data. An early example of the usage, in the article “Banks and Their Bonds” in the Wall Street Journal of December 23, 1936, describes the “value to an investment consultant of a cover letter from a bank that is seeking an outside opinion of its investment policy.” Describing this cover letter, it suggests that:

“Cover letter provides much needed information,” it concludes.

In its original incarnation, the “cover letter” provides an explanation for what can’t be found in the raw substance. Dotted throughout the 30’s and 40’s are other examples of the “cover letter” as in introduction to business, economic, or political matters—particularly between associates. Much like today’s cover letters, the original intent was to paint a picture that might not easily emerge from the denser material that was, well, under cover.

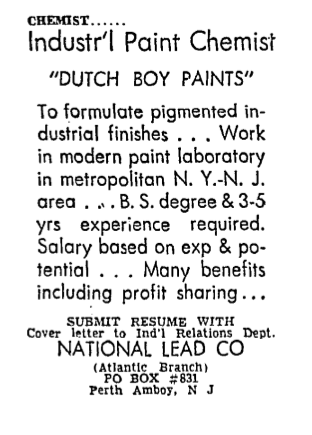

Yet, for nearly 20 years, we have no record of the cover letter, at least in name, being sought for employment. The first use of “cover letter” in the context of employment is on September 23, 1956. It’s in a New York Times classified ad for Dutch Boy Paints for an opening to be an industrial paint chemist (a position rather perfectly suited for da Vinci himself).

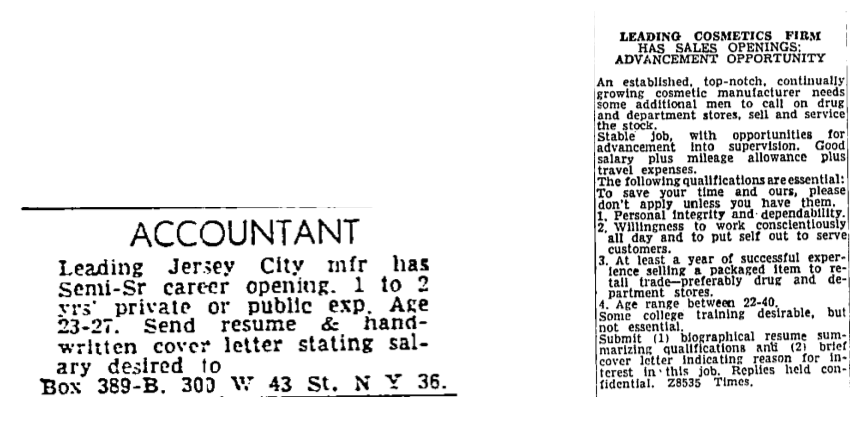

From this origin, the term was slow to replace both the more common vagaries of “particulars” or “background & experience.” After Dutch Boy, only a couple other firms—like a “First-rate American cosmetic company” and a “Leading Jersey City manufacturer”—would initially start using the term. The first instance where a cover letter was found in two different ads in the same paper was for an accountant position with the manufacturer and a sales opening with the cosmetic company. From the New York Times of October 6th 1957:

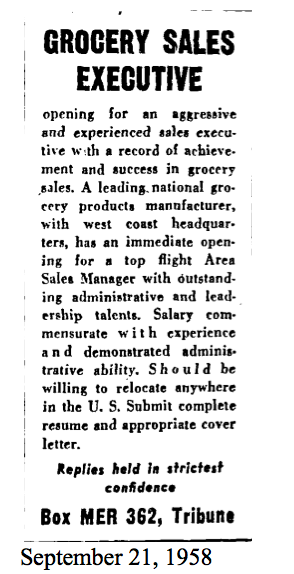

In 1958, the near simultaneous occurrence of the “cover letter” term in the four major newspapers—NYT, WSJ, Chicago Tribune and LA Times—suggests it was catching on. That ad, for an unspecified “Grocery Sales Executive,” was certainly for a company looking at national expansion.

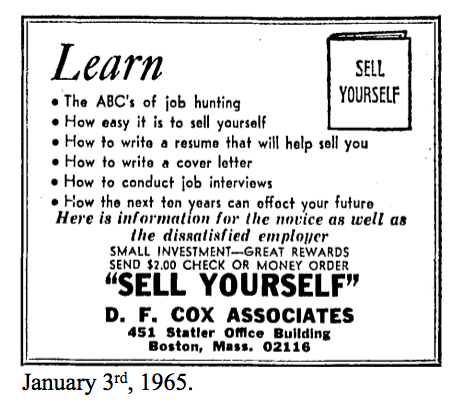

And the first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe:

If the cover letter’s origins seem mysterious, so does the art of writing them. Erwin Vogel’s How to Write Your Job-Getting Resume and Cover Letter, published in 1971, is still available for purchase online. But the 1990s were the heyday of cover-letter hysteria (as you can make out in the Ngram above). Book after book offered best techniques for bearing one’s soul efficiently on an 8.5-11” slip of paper. The milquetoast advice books have been replaced by milquetoast websites – and even more terrible slideshows -- all purporting to give advice on what is the very best in cover letter practice.

* * *

Getting a job in the U.S. didn’t always require such a performance. At the end of the 19th century, more more than 40 percent of the country worked on farms. At the end of the 1940s, more than one-third worked in manufacturing. Those were simpler times, arguably, when the labor market was divided into so many sectors and subsectors that required particular skills. Job-hunting, resume-revising, and cover-letter-crafting are new skills for a fragmented economy.

Unlike da Vinci’s simple CV, the cover letter is mostly a performance, and some companies are picking up on the act, particularly tech firms that can test specific employee skills. Google, it’s said, often prefers to see the coding already being done by individuals before reaching out to them—skipping the cover letter entirely. Some social media companies now require tweets as proof of competency, not long-form writing. For companies those that do still require cover letters (in whatever sector), many have simply stopped looking at them. Jobs that don’t deal in formal letter writing—let’s say 95% of them—can find better surrogates elsewhere in samples of a candidate’s work. Whether it is a writing sample relevant to the industry, a Github repository or other specific tasks, employers and candidates would be better suited to another test. That’s a good sign for us all. Our government, corporations and non-profits will invariably be stronger when they get the best-matched talent available—not just those who’ve mastered an irrelevant art.

Indeed, if we are to best serve the da Vincis of the 21st century we need to adapt our own new application tools. After all, who knows where we’d be if Leonardo had to use LinkedIn?