The Spectacular Rise and Fall of U.S. Whaling: An Innovation Story

An extinct business offers surprisingly current lessons about the triumph of technology, the future of work, and the inevitable decline of industries that might not be worth saving

"Some years ago -- never mind how long precisely -- having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world." -- Moby Dick

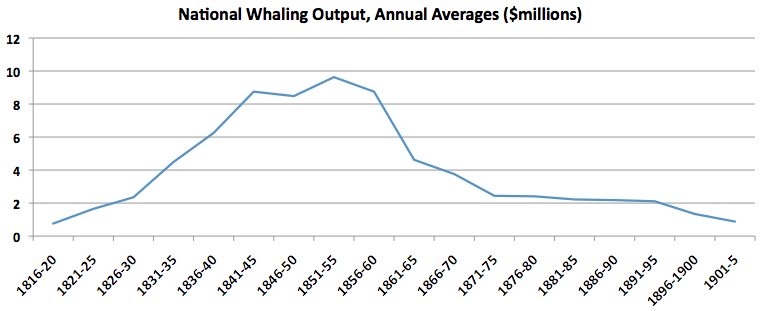

One hundred and fifty years ago, around the time Herman Melville was completing Moby Dick, whaling was a booming worldwide business and the United States was the global behemoth. In 1846, we owned 640 whaling ships, more than the rest of the world put together and tripled. At its height, the whaling industry contributed $10 million (in 1880 dollars) to GDP, enough to make it the fifth largest sector of the economy. Whales contributed oil for illuminants, ambergris for perfumes, and baleen, a bonelike substance extracted from the jaw, for umbrellas.

Fifty years later, the industry was dead. Our active whaling fleet had fallen by 90 percent. The industry's real output had declined to 1816 levels, completing a century's symmetry of triumph and decline. What happened? And why does what happened still matter?

BLUBBER!

Fat had never made a city so flush.

In the mid-nineteenth century, New Bedford, Mass., was the center of the whaling universe and the richest city per capita in the United States -- if not in the world, according to one 1854 American newspaper. The US whaling industry grew by a factor of fourteen between 1816 and 1850. Still New Bedford swallowed half of America's whaling output by mid-century. Demand for New Bedford's haul came from all over the country. Sperm oil could lubricate fancy new machinery. Inferior whale oil could light up a room. Baleen, or whale cartilage, could hold together a corset.

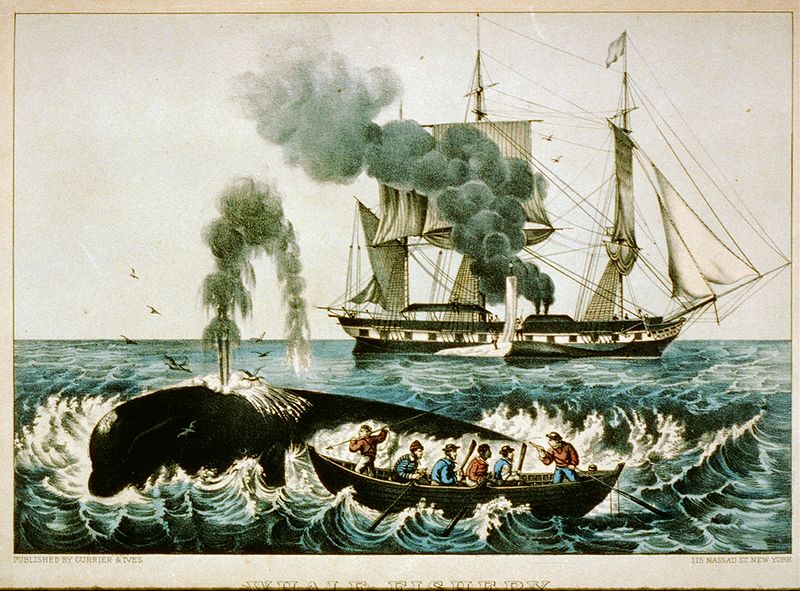

The thesis of Leviathan, the ur-text of whaling economics, is that the source of our dominance in the 19th century will feel familiar to a 21st century audience: a triumph of productivity and technology. Leviathan uncovers countless examples of innovation, but I'll limit our list to four areas. First and most broadly, Americans sailed bigger and better ships (like the barque to the left) guided by smarter ocean cartography and more precise charts. Second, a series of tinkerings with harpoon technology led to the invention of the iron toggle harpoon, an icon of 19th-century whaling and the unofficial symbol of the city of New Bedford.

The thesis of Leviathan, the ur-text of whaling economics, is that the source of our dominance in the 19th century will feel familiar to a 21st century audience: a triumph of productivity and technology. Leviathan uncovers countless examples of innovation, but I'll limit our list to four areas. First and most broadly, Americans sailed bigger and better ships (like the barque to the left) guided by smarter ocean cartography and more precise charts. Second, a series of tinkerings with harpoon technology led to the invention of the iron toggle harpoon, an icon of 19th-century whaling and the unofficial symbol of the city of New Bedford. Third, innovations in winch technology made it easier to pull in or let out large sails, reducing the number of skilled workers needed to man a vessel. It would hardly be hyperbole to say that winch tinkerings practically made the book Moby Dick possible. Melville could realistically populate his book with shady, far-flung, ragtag characters precisely because the vessel's technology had become so easy to maneuver, even an unwashed cannibal could use it.

Fourth, whale captains were innovators in employee compensation. In the lay system, "every member of the ship's company from captain to cabin boy signed on, not for a wage or piece rate, but for a predetermined percentage of the value of the product returned," Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, Karin Gleiter write. Savvy captains of the whaling barques, not unlike some creative corporate boards today, were keen to aligning company interests.

'YE DAMNED WHALE'

The standard explanation for the decline of whaling in the second half of the century is a pat two-parter consisting of falling demand (from alternative sources for energy) and falling supply (from over-hunting). But according to Leviathan, the standard explanation is wrong.

To be sure, energy preferences had been flowing to another source of oil: petroleum. In 1859, the US produced no more than 2,000 barrels of the stuff a year. Forty years later, we were producing 2,000 barrels every 17 minutes.

The answer from Davis, Gallman, and Gleiter will also look familiar to a modern business audience: US workers got too darn expensive, and other countries stole our share of the whale business.

Thanks to the dry-land industrial revolution, "higher wages, higher opportunity costs of capital, and a plethora of entrepreneurial alternatives turned Americans toward the domestic economy," the authors write. Meanwhile, slower growth overseas made whaling more attractive to other countries. "Lower wages, lower opportunity costs of capital, and a lack of entrepreneurial alternatives pushed [people like the] Norwegians into exploiting the whale stocks," they continue.

Between the 1860s and the 1880s the wages of average US workers grew by a third, making us three times more expensive than your typical Norwegian seaman. Whales aren't national resources. They're supranational resources. They belong to whomever can hunt them most efficiently. With all the benefits of modern whaling technology and workers at a third the price, Norway and other countries snagged a greater share of the world's whales.

As the costs of whaling grew, capitalists funneled their cash into other domestic industries: notably railroads, oil, and steel. When New Bedford's whaling elite opened the city's first cotton mill and petroleum-refining plant, the harpoon had been firmly lodged inside the heart of American whaling. Ishmael complained famously, in the first paragraph of Moby Dick, of having "nothing particular to interest me on shore," so he struck out to earn a living wage at sea. In the second half of Melville's century, the industrial revolution lured young men without means to factories rather than the ocean. Capital beckoned the nation's Ishmaels to the machines, away from the watery parts of the world.

***

The life and death of American whaling might seem like a precious nostalgia trip, but it's really a modern story about innovation. It's about how technology replaces workers and enriches workers, how rising wages benefit us and challenge companies, and how opportunity costs influence investors and change economies. The essay can stand on its own, without my muddying the waters with political points about how Washington or CEOs should learn from yesterday's Ahabs. Suffice it to say that whaling became the fifth largest industry in the United States in the 1850s, and within decades, it had disappeared.

And yet, perhaps with a mischievous sense of curiosity, some time late last Sunday night, I scoured my notes for a graph I remembered, which ranked US sectors by employment. Would you guess what the fifth largest sector in the US economy is today? It's manufacturing. The parallels are obvious, but also easy to overstate. Manufacturing is in decline as a fount of jobs, not as a source of production. But many of the reasons behind its labor decline -- rising wages, technology that replaced workers and enriched capitalists, and opportunity costs for investors looking for higher-margin businesses -- are old, indeed.

><