‘This Has Really Been a Blessing’: For Many Special Needs Students, Learning From Home During Pandemic Has Sparked Surprising Breakthroughs

By Jo Napolitano | May 20, 2020

School closures can be challenging for children with special needs, particularly those who rely on a team of teachers and therapists to access their education and who can’t replicate those services at home.

While the initial weeks of the shutdowns caused tears and frustration for many students and their families, they’ve also brought unexpected joys and triumphs as parents learn how resilient and capable their children can be.

Denise Stile Marshall, CEO of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, Inc., a national organization dedicated to protecting and enforcing the legal and civil rights of students with disabilities, was surprised by the number of parents in her network who reported positive developments with their children during the closures.

“Normally, we hear mostly from families who are struggling and who are in some level of dispute,” she said. “But we have heard from a number of families saying, ‘This has really been a blessing for us.’”

‘They are blowing my mind’

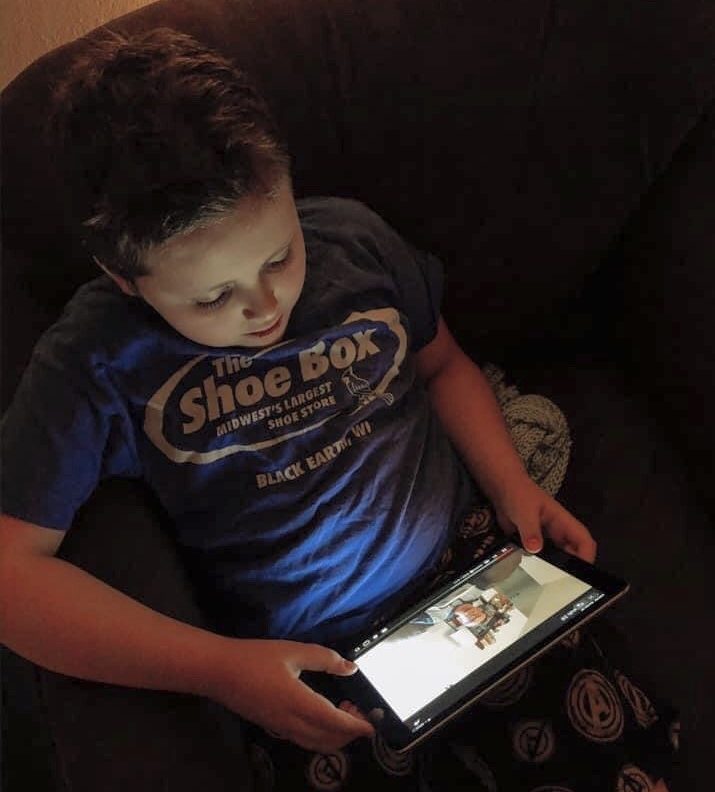

Both of Megan Hufton’s sons have autism and are non-verbal. Their last day of class at Wisconsin Heights School District near Madison was March 13. The boys’ private speech and occupational therapy sessions were canceled just days later.

Eight-year-old Asher cried about the closures every night, unable to understand why he couldn’t attend. “We took a trip to the school so he could see it closed and dark and covered with police tape,” his mother said. “He just stared at it very intently and was pointing. I said, ‘Yeah, no one is here, the parking lot is empty.’ We waved goodbye and started to walk home. He’d take a couple of steps and turn around and point again.”

Nine-year-old AJ was equally confused. He assumed the closures meant a change in season and kept adding a photo of a pool to a calendar he and his brother use to help express what they’d like to do each day. “I had to explain to him it’s not summer, we can’t go swimming,” his mother said.

Hufton worried about both boys’ ability and willingness to participate in distance learning. AJ struggled with the concept at first. “In his mind, we are home, and we don’t do school at home,” his mother said. “We were lucky if he would sit and engage for five or 10 minutes.”

But as the weeks passed, AJ began to adjust, working with his teachers for up to 30 minutes at a time. He’s done equally well with his teletherapy sessions, in which remote help is delivered via computer.

It isn’t an ideal setup. AJ doesn’t engage with the faces on the screen as much as he does with his mother. Still, his teachers and therapists are able to watch them and offer helpful advice and instruction.

“Is it perfect?” his mother said. “No. But is it working? Yes. We are making it work.”

“Normally, we hear mostly from families who are struggling and who are in some level of dispute. But we have heard from a number of families saying, ‘This has really been a blessing for us.’”

—Denise Stile Marshall, CEO of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, Inc.

But academics isn’t the family’s only concern. Hufton is using the break to focus on her sons’ life skills, helping them learn how to brush their teeth, dress themselves and prepare simple meals. “During the school year, it’s harder because there is a bus to catch,” she said. Donna S. Murray, vice president of clinical programs and head of the Autism Treatment Network at Autism Speaks, an advocacy and outreach group, said time off school and work allows parents greater opportunity to model these behaviors “and offer abundant praise and reinforcement for successes.”

Hufton also can postpone learning if one of her children is having a rough morning. “If they still had school, they’d have to be there from 8 to 3 no matter what,” she said.

And while her sons miss spending time with other children, the family has found a workaround: Their friends have recorded themselves reading bedtime stories — the list includes everything from Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown to The Foot Book by Dr. Seuss — for each of them.

“We can’t really jump on a Zoom call and have a conversation,” Hufton said. “We don’t have those same options that other kids do. But we are in an amazing school district, and the kids are fantastic with my boys.”

While AJ and Asher are making progress on multiple fronts, it’s their mother who’s learned the most important lesson. Back in March when states were contemplating school shutdowns, Hufton hoped Wisconsin would somehow be spared. She felt certain her children couldn’t handle it, but she was wrong.

“The boys have shocked me during this,” she said. “I’m so proud. They are blowing my mind with how well they are coping with everything.”

‘A very big relief’

Asher and AJ are among the 7 million students ages 3 to 21 who received special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 2017-18, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Stile Marshall, of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, Inc., worried that this population would be underserved during the closures.

She was right to be concerned: Half of those who have contacted her organization say they’re having trouble accessing services. Some school districts have failed to reach out to families at all, while others have not tailored the curriculum to students’ needs or have refused to send critical equipment that would enable a child to learn, she said.

It was the other half that surprised her. Those who have reported positive stories include a mother in Pennsylvania who is just discovering her daughter’s gift for art, another in South Dakota who spotted her little girl’s strength in math, a skill for which she is now doing advanced coursework, and yet another who was amazed by her son’s typing, writing and critical thinking skills, all of which were exposed through distance learning, Stile Marshall said.

“A lot, though, depends on the setup of the school and how much support — and what types of support — they are giving,” she said, adding that children tend to do better when their schools use many methods to reach them.

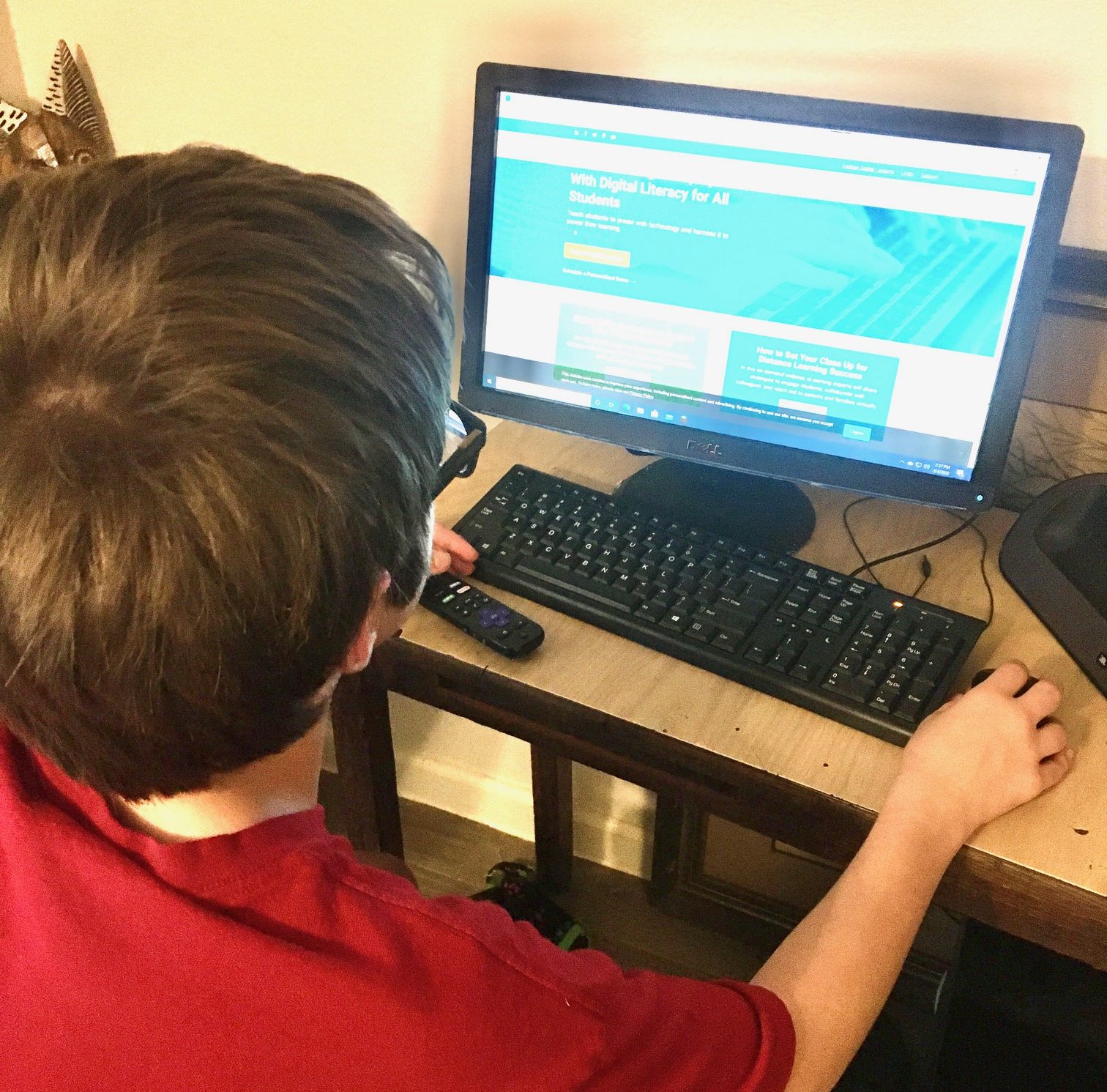

Tammy Baggett’s 14-year-old son, born with a heart defect that required surgery in infancy, wrestles with attention deficit disorder, anxiety and anger management. But it’s the dysgraphia, a learning disorder, that has caused Elijah the most trouble academically. People with dysgraphia often have poor penmanship, placing letters on top of one another or writing words without spaces between them.

“His brain and his hands don’t talk to each other very well,” said his mother, a high school biology teacher. “He has so many ideas he wants to share but has to concentrate so hard on how to get them to his hands in time.”

Distance learning, which is entirely computerized, has erased this problem from his life.

“It’s a very big relief,” said Elijah, a student at Wayne C. Schultz Junior High School in Waller, Texas. “For me, [writing] is very time-consuming, because I don’t have very good handwriting, so it’s hard for my teachers to read it. It’s very slow versus pressing keys on a keyboard.”

Distance learning also has freed him from the distraction of a noisy classroom, allowing him to slow down and focus on the details of his schoolwork, greatly improving his grades.

And much of his at-home instruction is pre-recorded, so he can stop and repeat what he doesn’t understand.

His mother said time at home has had other benefits, too: It has forced Elijah’s entire family to tackle long-standing behavioral issues that have caused him problems in the past.

“There is no escape to work or school,” Baggett said. “There is no coming home and starting to deal with an issue, but then you’re so tired, you just say, ‘Go to your room.’ Now, if he’s sent to his room, I’ll say, ‘Come out and let’s talk about it.’ I’m able to offer him more consistency.”

Elijah no longer has afterschool meltdowns as he sometimes did after a full day on campus. His mother is grateful for the break.

“Now, he can have moments when he doesn’t respond well and we can stop right then and there and handle that situation,” she said.

“There is no escape to work or school. There is no coming home and starting to deal with an issue, but then you’re so tired, you just say, ‘Go to your room.’ Now, if he’s sent to his room, I’ll say, ‘Come out and let’s talk about it.’ I’m able to offer him more consistency.”

—Tammy Baggett, mother of Elijah, who has dysgraphia, a learning disorder

Time at home also has helped Elijah improve his relationship with his 15-year-old sister, Mattie.

“The two of them are oil and water and I’m in the middle,” their mother said. “This has been good for them. They actually don’t fight as much because when they do, I’m right there. I close my laptop and say, ‘This is not going to happen.’ Whenever the world comes out of this, the three of us will have benefited from this time together.”

Linking cause and effect

Kimberly Peterson’s daughter Matilda “Tilly” Stapleton, 11, has a rare genetic disorder called Joubert syndrome. Though it is expressed differently from one person to the next, it usually results in myriad intellectual and developmental delays.

Tilly, of Knoxville, Tennessee, is unable to walk, talk or crawl. Though she is in the fifth grade, her behavior is more akin to a child of 15 months, her mother said.

Despite these challenges, Tilly adores Northshore Elementary School, where she learns inside a self-contained special education class for much of the school day. She squeals and claps when she sees familiar faces and works hard to meet the expectations of those who help her, whether it’s to try and stand on her own or recognize simple words and phrases.

Like many parents of children with special needs, Peterson worries that Tilly isn’t getting all the stimulation she needs: Her home is not filled with the yoga balls, platform swings and balance boards she enjoys at school.

“I do the best I can,” Peterson said. “But I don’t know all of the exercises and how to keep pushing her.”

Still, the family has adjusted well to quarantine. Tilly is medically fragile and has endured weeks-long hospital stays in the past, confined to just a single room. The current shutdowns aren’t nearly as difficult for her, her mother said.

Not only has time at home with a single caregiver offered Tilly more continuity, but it has allowed Peterson to spot a critical improvement in her daughter. Tilly has recently begun to connect how her actions can result in a particular outcome, a breakthrough that could drastically improve her quality of life by bringing her one step closer to communicating her needs.

“She is so delayed that understanding cause and effect is hard for her,” Peterson said. “Now she is making that connection. That’s a huge thing that wasn’t happening before.”

Her mother is grateful to have witnessed her daughter’s progress. Tilly also has had success using a simple, notebook-size communication device that allows her to choose among several different options, depending on the situation. It’s come in particularly handy during feedings.

“Before, I would feed her until she turned away,” her mother said. “Now, with this communication device, every time I feed her, she hits the ‘more’ button when she wants more or she hits ‘slow down’ when she wants me to slow down or ‘all done’ when she’s finished.”

Prior to this, Tilly’s only way to express dissatisfaction was to cry.

Peterson has noticed another positive development in her daughter. Tilly has become more affectionate, giving more bear hugs than ever before. While it’s unclear why, her mother suspects her constant presence has sparked the change.

“We are getting closer,” she said. “She knows I’m here for her.”

Lead Image: AJ Hufton, 9, who has autism and is nonverbal, surprised his mother with how well he adapted to distance learning. Initially, he had difficulty with the practice, and could only sit for five or 10 minutes at a time. But as he grew accustomed to it, he could sit for up to 30 minutes at a stretch. (Megan Hufton)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter