The Complete Guide to Pacific Northwest Berries

Tart and tender, sweet and even sacred‚ our local berries tell the story of the region. Our harvest is our history, ripened into a bounty of strawberries and huckleberries. We feast on wild blueberries and lab-born marionberries in summer, then flood cranberry bogs along the coast come fall. Our calendar is a fruitful one. Dig in—it’s berry season.

In Season

Strawberries / Raspberries / Blackberries / Blueberries / Huckleberries / Cranberries

STRAWBERRIES

In Season May–July

Strawberry Fields Forever

Bainbridge’s rich farming history weaves the stories of a changing island with the country’s traumatic past.

In late March of 1942, before the cherry red Marshall strawberries had even begun to form on their 40 acres of plants, the Suyematsu family walked away from the crop. Almost 15 years previously, Japanese immigrants Yasuji and Mitsuo Suyematsu purchased that Bainbridge Island farmland in their American-born son Akio’s name when he was eight; Asian exclusion laws prohibited non-citizens like them from ownership. Now they and other Bainbridge Islanders of Japanese descent became the first to be forcibly relocated to America’s World War II incarceration camps.

The Suyematsus were sent to California’s Manzanar Relocation Center, then Minidoka in Idaho; Akio, just graduated from Bainbridge Island High School, was drafted into the U.S. Army even as his family remained incarcerated. “Some of the Filipino community tried to help out with the harvest,” says Bainbridge Island farmer Karen Selvar. “Rumor has it, it was going to be a really good crop.” But efforts dwindled and the Suyematsu lands languished.

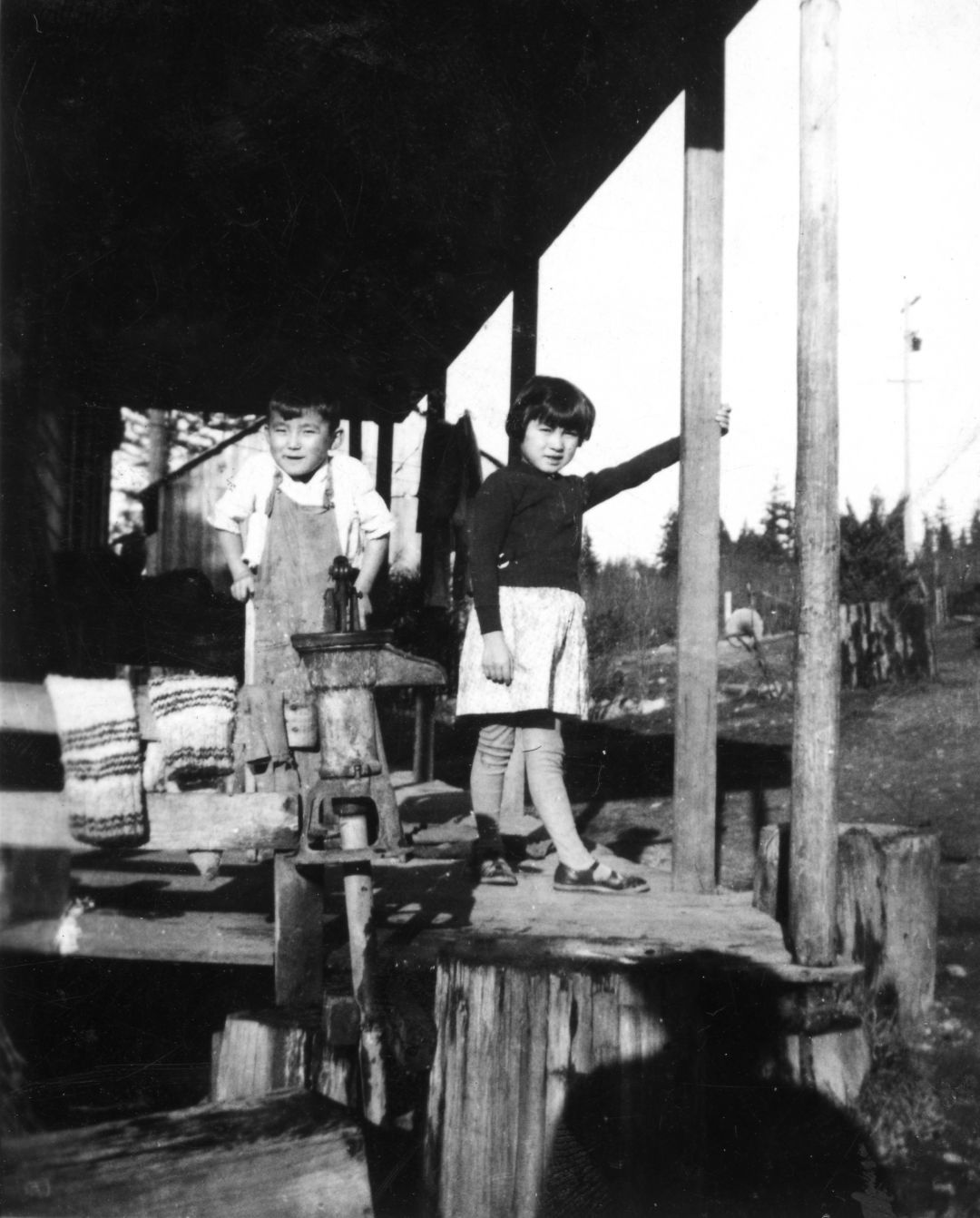

Akio’s siblings, Yasuo and Eiko, at the Suyematsu family farm circa 1935.

Image: courtesy dean Suyematsu

When the family returned after the war, they toiled to pay back interest on the farm mortgage. They rejuvenated a Bainbridge strawberry industry that had thrived for decades, producing two million pounds of fruit per year before the war, feeding an island cannery that had operated since the 1920s.

Not every farmer was able to claw their way back into production; most who did eventually sold land to the island’s booming real estate market. “He was one of the last holdouts,” Akio’s nephew Brian Shibyama remembers. “The land and the farming meant a lot to him, more than a business.”

Karen Selvar was nine years old when she first harvested strawberries at Suyematsu Farm alongside other island kids; she only lasted a week or so, making $4.25 that year. But she came back to work with Akio, year after year, and saw him branch out into pumpkins and Christmas trees. When Akio died in 2012 at age 90, she took over operations of the farm.

Only half an acre of Suyematsu remains devoted to strawberries, and in 2021 the heat dome of triple-digit temperatures blistered plants already ravaged by persistent black rot. But Selvar persists, her way of keeping the story alive of the hard-working Nisei farmers, of relocation and incarceration.

Selvar will replant that half-acre, these days with her favorite variety, Shuksan, named for a Washington peak. And in June, exactly 80 springs after the founders were forced from their lands, the Suyematsu harvest will come in. suyematsufarms.com

Image: Chona Kasinger

Berry Different

There’s something singular about a Northwest-grown strawberry.

It doesn’t look like a fair fight. In one corner, a fresh-picked strawberry from the Spooner fields of rural Thurston County, red as a stop sign and no bigger than a golf ball, a stem still protruding inches above its green cap. In the opposing corner, a behemoth of a grocery store strawberry. Raised under the vigorous California or Mexico sun, its beefy, triangular shape dwarfs its leafed end—technically it’s called a calyx—into a jaunty little hat.

The grocery store specimen looks like it could knock out the Spooner shorty in the first round before relaxing into a vat of melted chocolate. But taste-wise, the contest easily goes the other way, with the Northwest edition outperforming thanks to a kick of sweet juices. “They both shouldn’t be called strawberries,” says Sue Spooner of the comparison. “They’re a completely different thing.” She assumes you know which one deserves to keep the name.

Ronald Reagan was still in his first term as president when Tim and Sue Spooner began growing strawberries. Almost 40 years ago, the pair started to cultivate the plants grown by Tim’s father, Ken Spooner, churning the farm-fresh berries out of a 200-acre plot east of Olympia.

Picking begins at 5am in early summer, the flats stacked into vans to reach retail stands as far as Aberdeen, Purdy, and even the Wedgwood neighborhood in Seattle, every single strawberry plucked from the vines that day. The Spooners see the same employees return year after year, many of them school teachers and bus drivers looking for a summer gig. Even as prices have basically tripled from the Spooners’ first years, Sue agonizes over every dollar increase. “I like to see a mom get in her car, grab a half a flat of berries, and hand it back to the backseat for the kids to eat” while she drives away, says Sue.

The addictive yet ephemeral flavor of Spooner berries—a mix of Sweet Sunrise, Mary’s Peak, Puget Crimson, and Puget Summer varietals—comes from a higher sugar content than most. That also translates to a shorter shelf life, so the Spooners turn down most requests to sell wholesale to stockists who’d leave them on the shelf for two or three days at a time.

Strawberries are a notoriously finicky plant to raise, and the farm has added blueberries, raspberries, and marionberries to its menu over the years. But Sue says the couple couldn’t imagine retirement, her husband asking her, “Where would all these communities get their fresh berries?” Certainly not the grocery store. spoonerberryfarms.com

Best Bites

Molly Moon’s Homemade Ice Cream ► The staple strawberry flavor is made from fruit from Viva Farms, a project devoted to sustainable and inclusive farming education and production.

Seattle Shortcake ► Biringer Farms runs a shortcake shack in Seattle Center through summer and even into October, cramming the fruity concoction into a plastic cup for mobile consumption.

Pick It Yourself

Remlinger Farms ► Located in Carnation, the Fun Park section of the family-friendly destination offers pony rides and even roller coasters, and this year the farm adds a brewery; the joys of the strawberry U-pick are quieter but certainly classic.

Schuh Farms ► The family-run operation in Mount Vernon offers U-pick for eight varieties of berries, including strawberries, plus shortcake and smoothies served in their century-old barn.

Back to the top⤴

RASPBERRIES

In Season June–July

Jam Session

The Pantry’s berry expert breaks down the sweetest form of home canning.

"Jam is, like, my jam,” says chef Renée Beaudoin, who learned from her grandmother and passes on wisdom through classes at North Ballard cooking school the Pantry. She calls the process of opening her summer preserves magical: “I can feel the sunshine coming out of the jar.” Here Beaudoin breaks down her secrets to rapturous raspberry jam—her personal favorite.

Try the berries first. Rain and drought determine the best varieties of berry every year, and disappointing fruit won’t improve in the jar. “Whatever you can’t get enough of, that’s what you want to make jam out of,” Beaudoin says. She calls the raspberries from Sidhu Farms in Puyallup “the most glorious.”

Mix and match. Bramble berries, like raspberries and blackberries, can be blended together—along with loganberries, thimbleberries, salmonberries, boysenberries, and pretty much anything that grows on thorny, rough-barked bushes.

Don’t skimp on sugar. “It has a lot of sugar for a reason,” says Beaudoin, so reducing the amount noted in a recipe could be disastrous. Averse to the white stuff? Beaudoin suggests redirecting to a different product altogether, like a compote.

Use traditional techniques. Beaudoin prefers water bath canning, a method she’s seen fall off in recent years. Jam serves as a good entry into preserving foods at home: “Because there’s such a high sugar content, it’s very, very hard for it to go awry.”

Start small. “With one or two quarts, it’s very approachable,” says Beaudoin, and limited batches make for easy experimentation each time. Jars are best stored out of direct sunlight and cracked open within six months—right in the dead of a Northwest winter, when edible sunshine is needed most.

The secret is in the sauce: Beaudoin's raspberry jam.

Image: Courtesy the Pantry

Best Bites

Spinasse ► In summer, the Italian restaurant can dot its chicory salad with fresh raspberries, a combination that almost manages to compete with its famed tajarin pasta.

Raised Doughnuts ► The doughnut holes from an ex-Macrina Bakery chef take on a space-age feel with a coating of freeze-dried raspberry dust.

Pick It Yourself

Biringer Farm ► The Arlington growers—who also run the Seattle Center shortcake spot—trace their harvests back to 1948, today offering a rolling calendar of U-pick; not only do they have familiar berries but also tayberries (a raspberry-blackberry hybrid) and black caps (black raspberries).

Back to the top⤴

BLACKBERRIES

In Season July–August

Rise of the Frankenberry

Meet the marionberry, a cultivar, or variety, of blackberry bred at Oregon State University in 1945 as a hybrid of two existing types, the Chehalem and the Olallie. New berry strains are nothing new—more than 600 varieties of strawberries have been born out of the half-dozen wild versions—but the marionberry, named for Marion County around Salem, has been so successful it’s known by name.

Oregon produces nearly all U.S. commercial blackberries, some 40 million pounds, and marions make up more than half the acreage. But a challenger could be sprouting: In 2014, the same USDA breeding program produced the Columbia Star variety, much like the beloved marion—but thornless.

Salad, anyone? A goat chews blackberries in Issaquah.

The Clean-Up Crew

Introducing the blackberry bramble’s mortal enemy: the goat.

Like so many Pacific Northwesterners, Tammy Dunakin has a love-hate relationship with the blackberry. On one hand, they’re a tart late-summer snack, tiny globes of juice clustered together like a miniature bunch of grapes. On the other, Himalayan and evergreen blackberries are the most invasive species in our local forests, noxious weeds whose woody roots choke native plants and whose impenetrable thickets annex acreage with sinister, even mythic, persistence.

Dunakin, though, has another reason to love the thorned interloper: as lunch and livelihood for her 160 goats. As founder of Rent-a-Ruminant, she ferries her hungry horde of livestock between sites marked for clearing. Her goats mow down vegetation, in backyards and municipal sites, on Costco land and around stormwater ponds under the light rail—in spaces too steep or awkward for a human or machine. And 80 percent of her jobs include blackberries.

King County labels invasive blackberries as a Class C weed, recommending control of a plant whose cane can reach 40 feet and at a density of more than 500 canes per square meter. Vashon resident Dunakin formed Rent-a-Ruminant 18 years ago, but just how the animals eat blackberry thorns remains a mystery. Her goats are rescues and therefore a hodgepodge of breeds, Nubians and pygmies and LaManchas and alpine goat; all seem to have a way of “sucking them up like spaghetti” before crushing blackberry vines on their molars. “You’d think they’d hurt like hell, but they don’t. I’ve never had a goat with a bloody mouth,” she marvels.

Even with her gas-powered hedge trimmer, Dunakin struggles to cut a path through brambles (the prevalence of hornet nests doesn’t help). But her largest goat squad, 120 strong, can clear an acre in as little as four days: “It looks like napalm was dropped on it.”

Best Bites

Copper Creek Inn ► Just outside Mount Rainier National Park, the cozy roadside eatery has grown famous for its year-round blackberry pie—available to go but best served heated, a la mode, and after a long day of hiking.

Ellenos Yogurt ► In their two Seattle shops and in groceries nationwide, the marionberry flavor made with pureed fruit is one of its most popular.

Back to the top⤴

BLUEBERRIES

In Season July–September

Wild Blue Yonder

Mountain hikes for picking wild blueberries.

Come September, the slopes of the Cascades practically avalanche with wild blueberries, smaller and sweeter than the store-bought version. Amounts less than a gallon per person (plus or minus what you scarf down while picking) don’t require a forest service permit. Worried about competition? Our black bears are the real berry connoisseurs—they can eat up to 30,000 berries a day while bulking up—but staying on trail and making noise will keep them in their own berry patches.

Kendall Katwalk | 12 miles round trip

The Pacific Crest Trail section accessed from Snoqualmie Pass is most known for the sharp drop of catwalk blasted out of a cliff face, an engineering marvel. The miles leading up to the scary section are known for blueberries in fall; crossing the scary bit not required.

Cascade Pass | 7.4 miles round trip

Though in the heart of the North Cascades, this popular route is one of the most straightforward ways to get big mountain vistas on a shortish day hike. Blueberry bushes begin partway up the ascent to the pass, but the views are worth topping out.

Lake Valhalla | 7 miles round trip

The classic alpine lake at the top of this Stevens Pass area hike is a worthy destination year-round; snowshoers even reach its frozen shores in winter. In fall, an overlook above the lake turns a dusky red with ripening berry bushes.

Granite Mountain | 8.6 miles round trip

The bare slopes of the I-90 peak lead to a historic fire lookout perched on the top. Along the way the trail tracks through blueberry areas, though the huckleberry bushes are even more prominent. The berries are similar enough to mix and match.

Spider Meadow | 13 miles round trip

There’s good news and bad news: The hike into the mountains north of Lake Wenatchee is a rewarding trek that ends in a spectacular open basin, but further effort is required to reach most of the berries in this alpine area. But only a little more work—the fruit bonanza begins just above the meadow.

Wild blueberries: beloved by bears and hiking dogs alike.

Image: Allison Williams

Best Bites

Larsen Lake Blueberry Farm ► Bellevue’s parks department manages a historic farm that dates back to the 1940s, with U-pick operations running July to September most years.

Back to the top⤴

HUCKLEBERRIES

In Season August–September

This is huckleberry country, in the national forest east of Mount St. Helens.

Image: Michael Guio

Original Fruit

Huckleberries have been a part of Indigenous life for centuries, even as traditions face evolving threats.

Naiomie Wilkins unfurls her fingers to show off a cluster of huckleberries cradled in her palm. The fruit represents just a sliver of the day’s hand-picked harvest, gathered among the hills in the center of a triangle formed by Mounts Rainier, St. Helens, and Adams. The juice will stain her hands the color of port wine for days.

As a girl she came here, a stretch of the forest known as Pole Patch, with her grandmother and great auntie to pick huckleberries; now Wilkins, a member of the Nisqually tribe, brings her own children for eight days in late summer. “We try to get enough to last through the year, since this is the only time they grow,” she says. The older kids help pick, but what the younger ones find mostly go straight to their bellies.

Environmental anthropologist Joyce LeCompte-Mastenbrook calls the huckleberry “a romanticized berry in terms of its wildness, and also its amazing flavor profile.” Easily mistaken for the blueberry, the Western huckleberry is actually a wild strain of that fruit—but darker than the usual blue variety, often a blackish purple. To the tongue, a huckleberry’s flavor runs deeper, sharper, more complex.

In the food landscape of the Coast Salish, huckleberries hold a central culinary and cultural role rivaled only, perhaps, by salmon. For centuries Northwest tribes dried and smoked the berry, forming cakes wrapped in leaves or bark. By the 1930s non-Indigenous pickers thronged the rich forests east of Mount Adams known as the Sawtooth Berry Fields, but a 1932 handshake agreement between the Yakama Nation and the Gifford Pinchot National Forest reserved part of those lands for Native users.

Yakama tribal member Shawna Waheneka finds wild huckleberries.

Image: Michael Guio

No one has successfully domesticated the Western huckleberry, a fruit that thrives at higher elevations and produces few berries per plant. A 2007 report for the state’s Department of Natural Resources noted that their complex range and variable fruiting meant “It is not possible at the present time to precisely measure or even accurately estimate the quantity of wild huckleberries growing in Washington.” So commercial pickers get their berries in the wild, causing tension with local tribes; the forest service requires permits for large-scale personal or commercial harvest, but enforcement over a broad geographic range is difficult.

On a longer timeline, forest fire suppression has affected huckleberry meadows, whose plants need the conifers above them to be regularly thinned through purposeful fires. Global warming looms large; in recent years the berries have ripened even before the ceremonial August feasts that mark the beginning of the season.

On a wooded slope of Pole Patch, the distant volcanoes shrouded in clouds, Yakama tribal member Shawna Waheneka moves between the copper-red and dusky green leaves of huckleberry plants, gently plucking with both hands. A hand-woven belt of purple and teal and pink secures a basket to her waist, and a Seahawks hoodie keeps the mountain chill at bay.

Waheneka picks for family. Pole Patch is designated for personal harvest only, and the rutted forest roads are dotted with multigenerational campouts in late summer. But in the rolling Cascade hills around them, commercial pickers will gather at their own secret spots before selling their berries by the pound to buyers set up on Highway 12 in Randle. An industrious picker can gather 20 pounds or more a day, earning upwards of $200; the wholesalers then pass the fruit to makers of syrups, candies, and ice creams.

At home, Naiomie Wilkins will turn the family’s huckleberries into jams, pies, and pancakes for the rest of the year. The summer trips are the intersection of vacation, tradition, and sustenance. “It’s our traditional food,” she says. “And this is the only place to get it.”

Best Bites

The Station Cafe ► At the foot of Mount Adams, the Trout Lake eatery indulges in huckleberry pies, mimosas, and most of all, milkshakes in summer, served on the sunniest days at shaded creekside tables. 2374 WA-141, Trout Lake, 509-395-2211

Tieton Cider Works ► The berry fields around Mount Adams aren’t so far from Yakima’s cider producer, making its limited-edition huckleberry cider an unbeatably local combination of two signature state fruits.

Back to the top⤴

CRANBERRIES

In Season September–October

Cranberry harvest means waders and rakes at CranMac farms.

Image: Chona Kasinger

Bog Heaven

Washington’s coast doubles as a cranberry capital.

Waves crest on the Pacific shore, beating away at the flat Long Beach sands in restless repetition, but just a half mile inland the mist hangs still, a feel more Midwest than marine. One field, about an acre and a half in size, has been flooded with water to become a tidy, squared-off temporary lake, its surface crowded with tiny, bobbing pink balls. Here at the beach, it’s cranberry season.

Call it Washington’s forgotten berry, out of sync with the state’s summer juicers, its mountain crop. Here the berries are firm and hollow, tart and crunchy. They are harvested wet at CranMac farms, which produces about 10 percent of Washington cranberries—we’re one of the top-producing states, though far behind cran leader Wisconsin.

Malcolm and Ardell McPhail have been farming here since 1985, and like almost all Washington growers they sell to the Ocean Spray Cooperative; what their team collects will likely be dried into craisins, destined to add a tangy kick to salads and snacks. Each field is carefully flooded through a series of channels and dikes before a beater machine, well, beats the berries off the plants so the air inside makes them pop to the surface.

The CranMac crew can harvest several flooded fields a day.

Image: Chona Kasinger

Malcolm watches his crew harvest about 5,000 pounds from the field in just several hours. The berries are shoved onto a conveyor belt that dumps them into a truck like ball bearings. Watching the uniform floaters drift together and the steady stream fall into barrels is somehow intensely calming, like agricultural ASMR.

Ardell tells me to try one raw. “The first one is always sour,” she warns. “The second one is sweet.” The requisite chomp to get through the cranberry’s firm texture feels almost akin to eating a vegetable. The tart flavor feels bright, a bit more robust than a summer berry, better suited to the fall and winter holidays where it will take center stage.

Nearby the Cranberry Museum tells the story of the local industry, including how an invention from Grays Harbor revolutionized the dry harvest method; both techniques are used in the state. Though the commercial farming on the Washington coast dates back to when a nineteenth century visitor noticed the climate similarities to cranberry-rich Cape Cod, Native tribes ate wild cranberries here long before that.

As Malcolm McPhail oversees harvest in his fourth decade of farming, he hasn’t lost his appreciation for the robust little berry. I ask if he eats his own crop often. “Are you kidding? I have my cranberry juice every morning,” he says. “And cranberry sauce on everything.”

Best Bites

Cranberry Museum ► Part gift shop and part educational museum, the former research center includes demonstration fields, ideally viewed during a stroll with a cup of their signature cranberry ice cream.

Pickled Fish ► The top-floor bar at Long Beach’s Adrift Hotel works cranberries into cognac cocktails and a signature margarita, as well as the nonalcoholic cranberry lemonade.

How to Not Poison Yourself

Top row: holly berry, climbing nightshade, snowberry. Bottom: snakeberry, devil's club, elderberry (raw).

Luckily, most berries found in the Pacific Northwest will cause, at worse, an upset stomach from overconsumption. But some toxic varieties exist, including holly (decoration yes, dinner no) and climbing nightshade (steer clear of its egg-shaped berries). Both the red baneberry, aka snakeberry, and devil’s club are aptly named. The common snowberry? That’s a no berry.

Only ingest wild berries you can properly identify; check Washington State University’s comprehensive PNW Plants searchable database (pnwplants.wsu.edu) or the state department of transportation’s online guide (search wsdot.wa.gov for “berry”).

Back to the top⤴