- Ever since the first Europeans came to China, outsiders learning the language has come with its own challenges and rewards, right up to the present day

In 1582, Matteo Ricci arrived in Macau, with the aim of converting the Chinese to Christianity. But to do that, he would have to become accustomed to the mores of Ming China, including its language.

“Many of the letters have the same sound, even if they are represented by a different character, and each one signifies many things,” he wrote. “Even among eloquent people, literati, who pronounce the language well, the Chinese often ask one another to repeat a word, and to say how it is written […]”

The Italian of the Jesuit order would eventually master Chinese, inspiring generations of missionaries and merchants to attempt the same, but few thereafter would breach this great linguistic wall.

By the tail end of the 19th century, however, attempts to regulate foreign activities were failing. The Qing dynasty (1644-1912) had fallen technologically behind the West, and foreign esteem for all things Cathay – an alternate, historical name for China – had declined. A few still attempted to unlock the mysteries of the language, although many relied on pidgin, a hybrid language developed in the treaty ports. Or they simply used translators.

Dismayed by a perception of civilisational decline, Chinese reformers of the time advocated for the wholesale abandonment of characters, including the writer Lu Xun, who hyperbolically argued, “If the Chinese script does not go, China will certainly perish!”

Cantonese’s future is uncertain – meet those preserving it in creative ways

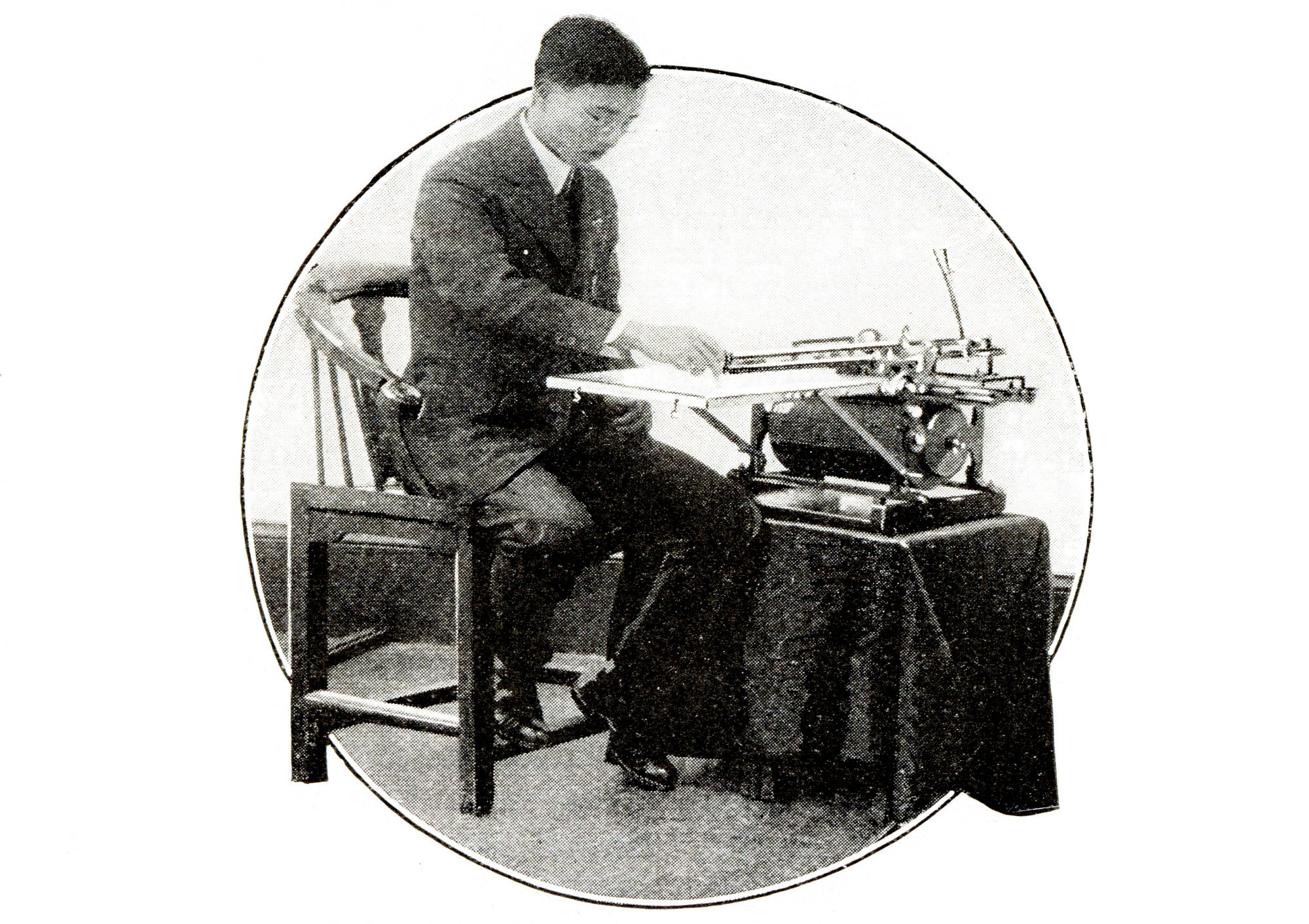

But perish it did not. As documented in Jing Tsu’s book Kingdom of Characters (2022), through the efforts of pioneers such as Wang Zhao, who came up with the Mandarin Chinese Harmonic Alphabet in the 1900s, and Zhou Houkun, who masterminded the first Chinese-language typewriter in 1916, the Chinese cultural universe was spared the salvoes of the modern era.

The Sino-curious usually had to head to the Republic of China, better known as Taiwan, to live and breathe Chinese, which is what American linguist Bruce Humes did in 1978, arriving in Taipei with US$200 in his pocket and a mission to master the lingo.

Humes, who already had some Chinese language from university, set about adapting to his new cultural habitat. “People welcomed you to China,” Humes recalls of pre-democratic Taiwan, “and classrooms had maps that included all of the mainland with Taipei as the capital.

“The Taiwanese accent meant people could understand me, but I couldn’t understand them at first. Dictionaries all used bopomofo [an older transliteration system than pinyin, still popular in Taiwan], which I had to learn.”

“In 1979, [United States] President [Jimmy] Carter recognised the PRC,” Humes says, alluding to what the Taiwanese termed “the great betrayal”, when Washington derecognised Taipei in favour of Beijing. “My days at university were interrupted by the pushback over US recognition of the mainland and after 10 months I moved on to Hong Kong.”

Two decades later, when writer and publisher Harvey Thomlinson turned his attention to Chinese, the era of reform and opening was in full swing and Beijing had emerged as a popular destination for overseas students.

“It was the dawn of the Asian century and a lot of people were thinking it might be a good time to study Chinese,” says Thomlinson. “Qianlong must have been turning in his grave.

“Our class at Capital Normal University was a hotspot of multicultural interaction; Korean students who saw China as a land of endless opportunity; a cohort of British undergrads, intent on recreating the hedonistic UK college experience; a smattering of Russians with an unshakeable grasp of the phonetic alphabet; and one term, several US Marines, all firm fans of President George W. Bush.”

[Pleco] updates with new features all the time. It even notes the differences between Taiwan and mainland MandarinImogen Parsley, Cambridge University Chinese studies major

Thomlinson notes that this was “the time of the dot-com boom” although this did not translate into any hi-tech teaching methods in a country that remained nominally poor.

“The only classroom technology available was the video recorder used for listening practice,” Thomlinson recalls. “My most important study aid was the little red dictionary.”

This commodity – the Pocket Oxford Chinese Dictionary – was still ubiquitous by 2005, when state television ran daily Chinese for foreigners programmes hosted by Canadian Mark Rowswell, better known by his Chinese name, Dashan, augmenting classroom studies that were still dominated by colourless textbooks and phrases such as “The scenery of Guilin is beautiful” over more practical concerns like “Can I have a bowl of noodles, please?”

Notwithstanding some cultural misnomers, a student of Chinese in the first decade of the new millennium was the beneficiary of linguistic and technological advances that would have made a 16th century Jesuit such as Ricci green with envy.

The 1912 Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation had decided upon the Beijing dialect as the basis for the national tongue, and 50 years after the conference, Mao saw to it that more than 2,000 characters were simplified (a number that has since surpassed 8,000) and introduced a standardised phonetic system using the Roman alphabet called pinyin.

And thanks to the pioneering efforts of scientist Zhi Bingyi in the 1970s, characters that had first appeared carved into Shang dynasty (1600-1046BC) oracle bones could now be processed by computers.

“I mostly use Pleco,” says Imogen Parsley, a 22-year-old Cambridge University Chinese studies major who has just completed her year abroad at National Taiwan Normal University.

The digital dictionary to which she refers, identifiable by its traditional yú “fish” logo, is something of a Chinese-language Swiss army knife, equipped with inputs ranging from pinyin to hand-drawn characters to optical recognition.

Pleco can provide learners with a given character’s stroke order, notes on common idiomatic phrases, and even play how a word sounds – all timesavers for anyone facing the challenges of a character-based language.

“It updates with new features all the time,” says Parsley. “It even notes the differences between Taiwan and mainland Mandarin.”

Parsley may be studying in a traditional university setting, but the migration to online learning has seen Chinese copied from textbooks and pasted onto the virtual walls of social media. And this remote-learning trend is not just freeing students from the classroom, but teachers as well.

At university, Lam took on a fourth language as part of her European studies programme, opting for French, and this led to a master’s degree in France, which she now calls home.

“Growing up in Hong Kong,” she says, “I knew that I would never own my own apartment, and the political situation, well, you could feel the tension for a long time.”

She may have drifted far from the shrimp farms and mist-shrouded hills of the New Territories where she grew up, but Lam’s Chinese skills have served her well in Europe.

Finding regular employment as a translator in the industrial sector, it was not until two years ago that Lam decided to break from the corporate world and become her own boss. Inaugurating her website as Ms Lin Chinese at the onset of a pandemic turned out to be auspicious.

“I had been teaching [for free] just to help people at first,” she says. “Eventually, I told myself ‘now is the time’ and I handed in my resignation letter a month before France went into full lockdown.”

When Hong Kong’s fight against smugglers in speedboats turned deadly

Lam regularly takes part in live streams as well, often in discussion with fellow Chinese teachers from around the globe such as Spain-based Wang Benfang, known by his internet epithet Ben Laoshi, on a range of topics, such as the difference between francophone and hispanophone learners of Chinese, or how life in France or Spain differs for a Chinese instructor.

Wang hails from snowy Heilongjiang province, some 3,000km (1,860 miles) north of Hong Kong, and came to teaching almost by accident after graduating with a master’s degree in international business in Miami, in the US.

“I applied to work in a bank in Washington DC,” he says, “but I found out there are many language schools in the DC area that teach diplomats, and they pay well.”

Wang taught American elites for a year until his OPT (Optional Practical Training) visa expired, then returned to China, where he honed his profession teaching in Beijing’s Chaoyang district, where many embassies and international offices are located.

“During class time in Florida, people spoke English but after class everyone started speaking Spanish,” he says. “They were all Latin American.”

Wang studied part time at the Instituto Cervantes de Pekin and made Spanish friends in the Chinese capital who recommended he decamp to Europe to perfect his linguistic skills.

“I tried to accumulate as many students on online platforms like Italki and Verbling as possible so that I could be independent and explore Europe,” he explains. Now living in Madrid, Wang, like Lam in Montpellier in the south of France, is financing his overseas adventures by teaching online while perfecting a language, even if he is not travelling quite as much as he had planned.

“Spain is much cheaper than France and I only need to teach 15 hours a week, not 20 like Miss Lin,” says Wang. “But I’m a workaholic so I teach 40 hours a week, including weekends.”

One only has to search Instagram to see the league of would-be Mando-professors jockeying for your attention, be it Handsome Chinese, Chinese with Jen, Chinese with Richard, Chinese Teacher Lucia, Takeaway Chinese, Jiayou Chinese … the list goes on.

They swam to Hong Kong in waters that promised death to escape a worse fate

The content these “teachers” produce to entice students is often prosaic, usually involving a short clip with a rhetorical question about Chinese vocabulary. But some stand out from the pack, such as the outspoken Keren Liu, who recently collaborated with Wang on a YouTube live stream concerning her path from southern China to a life in the US.

“When I was looking online the other teachers there were so boring,” she says, explaining her idea to create earnest but provocative videos. “They would just say this is blah, blah, blah, there’d be an English-Chinese caption and they’d add, please follow me.

“When I make a video, I don’t have a draft. I just look at something and I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s something I would want to talk about.’ And I just start recording myself. It’s really casual.”

To this end, Liu has turned her social media accounts into an online Chinese-language diary, documenting her daily experiences, be they getting accosted at the gym by an unwanted suitor or her opposition to the US Supreme Court’s ruling on abortion rights.

“My ex-boyfriend always told me, ‘You’re so unconventional,’” says Liu. “I was like, ‘What does that mean?’ He told me, ‘You’re this tiny Asian woman who people expect to be obedient but you act like you’re the big boss.’”

Liu’s character might well have its roots in the red earth of Hunan – a province known for its feisty la meizi, or spice girls – where she was born, but she identifies with the city in which she came of age, just across the border from Lam.

In her youth, Liu’s role models were teachers and she developed an early love of the Chinese language. But she also dreamed of going to America, especially as affluent Shenzhen peers returned from studying overseas.

“They told me, ‘Keren, your personality is so suited to the US.’” But lacking the finances, Liu wound up at South China Normal University, in Guangzhou, instead.

“It’s a good university but I just felt like everybody was doing the same thing as in high school,” she says. “Goddamn. They were just reciting everything and trying to get a high score. It was so boring.”

Cantonese is far from dead. It’s cooler than Mandarin and has cult status

Liu began applying for a placement on a Sino-US exchange programme, and after two rejections, her third attempt saw her heading stateside, to Oklahoma, a place she describes as “somewhere a bird wouldn’t even poop”, rather than Los Angeles, as she had initially hoped.

The Midwest might not have represented her American dream but it was a stepping stone. Liu was able to teach in a nearby Confucius Institute while studying for a master’s degree, and after graduating she has taught her way across the US, working in Texas, Colorado and California, that is, until she hit a moment of crisis: “I realised, this is boring as f***. So I just bounced. I was thinking, ‘Should I still be a teacher or should I completely shift my career?’”

With the money she had saved, Liu decided to embark on a journey of self-discovery while contemplating what she wanted to do with her life. She made it through Latin America, back to China and travelled parts of Australasia before the pandemic derailed further travel plans.

Yet it was during a Covid-19 lockdown that she had an epiphany: she would teach online while reorienting her career towards business.

“People had asked me to teach them before but I’d told them I had no time. But while I was in Queensland the pandemic hit so that’s when I started marketing myself and accepting more students.”

Now Liu is using “Unconventional Chinese” to teach without the classroom rules she found prohibitive, pursuing the methodology that “teachers shouldn’t translate to teach […] That’s not how human brains acquire languages.

“My philosophy stems from [linguist] Dr Stephen Krashen’s theory of comprehensible input. He believes we should learn a second language like babies learn their first language, which is through input.”

She now is back in the US, financing her MBA programme in New York by teaching online.

“I thought, I have to combine comprehensible input with an interesting way to promote it. That’s why I call my website ‘unconventional’. It’s my personality. And it’s the teaching method,” she says.

Unlike Lam, Wang and Liu, who live overseas and are the beneficiaries of a free and open internet, the bulk of Chinese-language instructors still live in mainland China, where the main way to circumvent the Great Firewall is with a virtual private network (VPN) known as a fan qiang, literally “to climb over the wall”.

Throughout human history, language has separated us more than race, creed, or cultureJames Griffiths, writer, in Speak Not: Empire, Identity and the Politics of Language

But while VPNs might be widely used, they are illegal. This is perhaps why, of the 10 mainland-based teachers approached for this article, only one agreed to speak before having second thoughts and requesting not to be quoted, nor to “mention VPNs”.

Across the strait, Linus the Taiwanese is the moniker of Taichung-based Chinese-language teacher Liu Yicheng, who enjoys full internet access, which may prove a boon given the current political rift rattling the sinosphere like it has not since Humes studied Chinese in Taipei in the late 1970s.

Though Liu remains diplomatic about the current geopolitical shifts, even admitting “I teach pinyin” and “traditional or simplified characters depending on student’s needs”, he does “treat myself as a brand, I’m from Taiwan so I call myself Linus the Taiwanese”.

“And I don’t just see myself as a Chinese teacher but as a content creator, as someone who spreads culture. So if you want to know more about Taiwan, I’m the one that you can look for.

“We have free speech, you can say whatever you want,” he says. “For students that means they have more chances to speak different sentences […] I encourage my students to talk about whatever they want.”

Despite such freedoms, there are, of course, differences in accent, vocabulary and the fact that Taiwan maintains traditional written characters, projecting itself as a “guardian of traditional culture”.

Justin Winslett, who teaches Classical Chinese at Oxford, Cambridge and Sheffield universities, says, “Universities like Sheffield have relied on online learning. But currently, the Oxbridge second-years all go to Taiwan. This has been practised since China has locked down. And this is an arrangement for the next academic year as well.”

Although Winslett notes “the arrangement has not been made permanent” the chill in East-West relations of late is helping to reset the clock, with radical implications for the next generation of budding sinologists.

“So language fascinates, but it also frustrates,” writes James Griffiths in his introduction to Speak Not: Empire, Identity and the Politics of Language (2021). “Throughout human history, language has separated us more than race, creed, or culture.”

Such “fascination” and “frustration” are as manifest as yin and yang, for just as the internet has made Chinese the world’s second largest linguistic community behind English, and technology is giving Chinese learners a digital toolkit of online resources to aid their studies, so is human politics muddying the waters where linguists wish to bathe.

Ricci knew this as far back as when Ming suspicion saw him hounded out of Zhaoqing in 1589 by the new viceroy of Guangdong and Guangxi.

What unites Ricci’s experience of painting characters with ink and scroll on the banks of the West River with his contemporaries creating flashcards on an iPad in a flat in Taipei is that Chinese is nothing if not challenging, and that those challenges have never been uniquely linguistic in character.