Polarized America agrees on one thing: that the current round of protests against racist police violence may indeed force real reform. Former president Donald Trump said that protesters want to “overthrow the American Revolution” and that the National Guard and regular military must act decisively to “dominate the streets.” Black Lives Matter activists worry that these protests, like so many over the past few decades, will eventually subside, leaving temporary concessions, symbolic victories and an unaltered regime of systemic racism, along with unabated police violence.

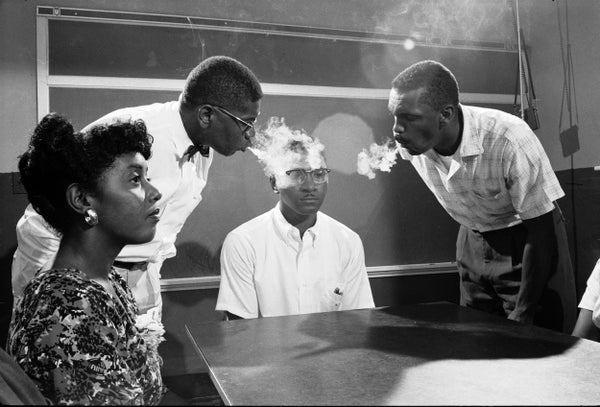

History shows us that Trump and others like him have some reason for fear—not of an actual rebellion but of a revolution that could overturn the racism that still pervades American society. Starting in the 1950s and continuing until the 1970s, civil rights protests overthrew the century-long and deeply embedded Jim Crow system in the South. How they accomplished this can offer important lessons for those intent on making Trump’s fears come true.

In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King, Jr., succinctly summarized what he hoped the Birmingham campaign needed to accomplish to force durable structural change: “The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.”

These words were written in the midst of a comprehensive and sustained struggle to create chronic disruption in the city of Birmingham. Large contingents of protesters marched into—and refused to leave—the major downtown department stores; conducted sit-ins in virtually every inch of public space; and clogged all the major thoroughfares in the city. No customers could enter stores, no goods could be delivered, and no business was being conducted. The effort by public safety commissioner Bull Connor to “dominate the streets” using barbaric police violence against the demonstrators failed; instead it provoked even more disruption and larger protests. And further arrests were impossible because every jail in the city was filled far beyond capacity.

As King had predicted while incarcerated for his participation in these protests, a crisis-packed situation was achieved. And as soon as the business leaders and political elite realized that the demonstrations were indeed chronic, they negotiated with movement leaders, agreeing to dismantle racial segregation in commerce and public services.

These crisis-packed protests led to the eradication of Jim Crow laws and “Whites Only” signs and ultimately gave way to a regime change across the South. The creation of crisis-packed situations across the South resulted in the enactment of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. As I write in my book The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement, contrary to the sanitized, rose-colored-glasses version of history, change was not generated through nondisruptive marches of people singing “We Shall Overcome.” Whether the Black Lives Matter movement creates meaningful and lasting change depends on the degree to which it disrupts regimes of racial inequalities and can sustain that disruption until the captains of white supremacy are ready to negotiate.

The movement has made a good start toward creating and sustaining crisis-packed situations across the U.S. Triggered by the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota, mass demonstrations in every state and scores of other countries have been disrupting “business as usual” in virtually every realm of life. On the ground in countless cities, the movement has been replicating King’s Birmingham strategy, filling streets and shopping areas with protests that prevent access to stores, interfere with deliveries and drive away customers, creating—in the midst of the massive disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic—a chronic crisis in business districts.

The protests are disrupting police routines—including their routine use of excessive violence against communities of color—and forcing them to restrain their wrongdoing in confronting legitimate protest. The confrontations between police and protesters have produced high-profile police misconduct that has led, as it did in Birmingham, to larger and more disruptive protests, promising to create the chronic crisis that King prescribed as the necessary prerequisite for meaningful negotiation.

The protests have dominated television, print and radio news cycles and have riveted attention on systemic racism. New voices and ideas are penetrating the media and disrupting the ingrained loyalty to many of the cultural practices and symbols endorsing and enforcing racism. Protesters have toppled and removed Confederate monuments from public places, gaining, for the first time in decades, the attention of major media and forcing government and private institutions to remove symbols of white supremacy from public display.

The protests have disrupted America’s claim to moral leadership in global affairs, especially when Trump advocated and acted—as he did in Lafayette Park in Washington, D.C.—to “dominate the streets” with military attacks on those protesting violent police assaults. And like Connor’s efforts in Alabama nearly 60 years ago, these attacks have failed, producing larger and more disruptive protests.

So far the disruptions have yielded symbolic changes, including changing flags, replacing monuments, renaming buildings and streets, amending music lyrics and altering our vocabulary of discourse. These changes are hard-won and important, but the eradication of these symbols of white supremacy does not ameliorate the material hardship of systemic racism. They are the first concessions granted because they are not expensive. The toppling of Confederate statues can produce hurt feelings, humiliation and even homicidal rage among those who cherish the symbols of white supremacy, but they do not cost billions of dollars.

The structural changes that can reduce or eradicate systemic racism are altogether different from cultural changes. They require the reallocation of basic resources to equalize income and wealth, employment and underemployment, educational opportunities, incarceration rates and access to quality health care.

Structural changes are very expensive to implement, and they involve a zero-sum logic that places powerful institutions on the wrong side of history. They involve transferring money currently earmarked for police weaponry to underfunded schools in Black communities; slashing the military budget to finance low-income housing; and taxing obscene levels of executive pay and bloated corporate profits to make the minimum wage a living wage. To achieve structural changes, widespread and sustained social disruptions must continue until the powerful people and institutions whose funds are needed for equalization are ready to negotiate.

This is a unique moment in American history. The crucial question is whether current or future white and Black leaders of these powerful institutions appreciate that chronic crisis can only be ended if they negotiate the changes needed to move the country toward the democratic ideals it put on paper centuries ago. There are glimmers of hope that the current protests have been sufficient to compel negotiations that have already led to some reforms (outlawing choke holds, for example) and put more on the table for the first time, such as defunding the police. If these initial signs do not mature into systemic reform, then national crisis-packed disruption will be needed to move the U.S. toward a more perfect union.