The pandemic’s impact on children has been so uneven that many U.S. classrooms now have a wider range of student abilities, with more students lagging far below grade level, new testing data shows. That’s made teachers’ jobs more difficult and put the prospect of academic recovery even further out of reach for many students.

While classrooms have always had a mix of students, with some above grade level and some below, research from NWEA — a testing organization that analyzed math and reading tests given to 8.3 million students in grades three to eight in the last three years — shows that the pandemic has exacerbated those differences.

That means that the “crazy hard job” that teachers had before the pandemic has only gotten more so, making it less likely that children are getting enough support to succeed, said Karyn Lewis, director of NWEA’s Center for School and Student Progress, who analyzed the results of the organization’s MAP Growth assessments.

“We’re probably not doing a good job at supporting our exceptional children and getting them to get their needs met,” Lewis said in reference to students who are above grade level. “But I think the biggest concern is, of course, for students that, if we’re taking a triage approach here, those kids that are well below grade level. They might be in a classroom with a teacher that just isn’t equipped to help address those needs.”

The concern is even greater in schools with high concentrations of poor, Black or Latino students, where children fell even further behind during the pandemic and have more ground to make up.

Students have also changed in other ways, teachers say, with some grieving loved ones who died from Covid-19 and many showing social and emotional immaturity after spending months or years in online classes instead of interacting with their peers in person. Many schools have reported more behavioral issues among students as a result.

The wide variation among students that NWEA identified in its analysis has only intensified the challenge of ensuring that all children are making progress, teachers say.

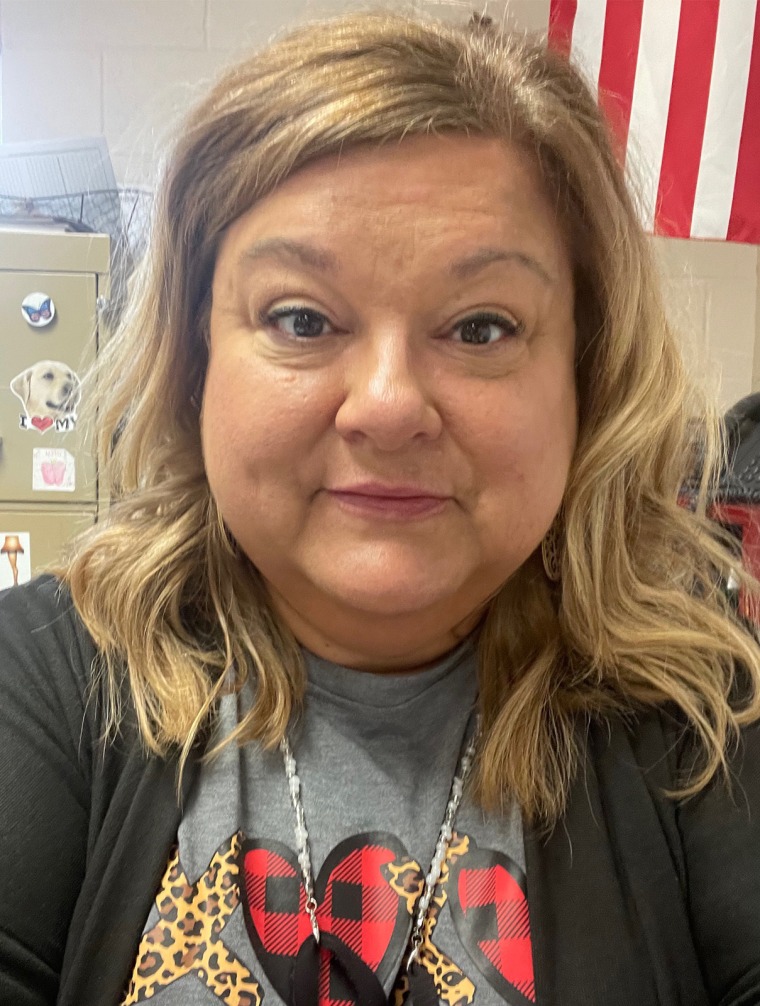

“This has been the hardest year of my teaching career,” said Amber McCoy, 48, a fourth grade teacher at Kellogg Elementary School in Huntington, West Virginia, who has been in the classroom for 20 years. “They want us to resume school as normal but it’s nearly impossible.”

Some of her students had actively participated in lessons the previous year, when instruction was hybrid — mostly those who had more support at home — which left them in a very different place than peers who drifted away when classes went online.

“The students that had remained engaged were ready to go,” she said, but many students showed up last fall with academic and emotional needs that teachers had to diagnose and figure out how to address.

“All of those things just factor into the widening gap between the kids who are OK, have always been OK and will continue to be OK, and those kids who were just hanging on and are now falling behind.”

The NWEA analysis of variations among students was based on MAP Growth assessments, which are administered two to three times a year in over 24,000 schools — roughly a quarter of the nation’s elementary and middle schools.

The study found that students in grades three to eight showed a larger spread in achievement levels this spring compared to the spring of 2019. In reading, the spread of student achievement levels was 4 to 8 percent wider than before the pandemic, Lewis said. The differences were even more pronounced in math, especially in grades three to five, where the range of student scores was 5 to 10 percent wider than three years ago. Most of the new variation was related to more students lagging further behind their peers than in the past, she said.

At Greensburg Salem Middle School in Pennsylvania, that’s meant that while before the pandemic, teachers might have broken students up into three or four ability groups for a math class, this past year they needed six or eight ability groups, said Shawna Burger, 40, a math specialist who supports teachers in the school.

When Burger shared testing data with teachers last fall showing the wide variation among their students, they were alarmed.

“Panic ensued,” she said, recalling teachers throwing up their arms and declaring “there’s no possible way I’m going to be able to do this!”

She counseled the math teachers in her school to adopt new ways of teaching. The old “stand and deliver” method where teachers give lessons from the front of the classroom, usually playing to the students in the middle of the class’s ability range, had been discouraged by teaching experts even before the pandemic. That approach excludes students who are struggling academically and those who need more of a challenge.

Now, Burger said, with an even broader range of needs in the classroom, lecturing from the front of the room is even less effective. Teachers need to break students into small groups, she said, putting some on computers and matching others with their peers so they can work independently while teachers and aides move around the classroom, spending time with each student or group.

Burger hopes this approach will yield better teaching going forward — potentially an enduring positive legacy from the pandemic — but, for now, she said, her school is still playing catch-up.

“We cannot expect to fix this in one year,” she said.

Earlier in the pandemic, NWEA’s analysis of test score data showed that Covid quarantines and distance learning had disproportionately affected Black and Hispanic students and students who are poor.

Two years later, there are signs of improvement across all demographic groups. Schools with high concentrations of poor students are gaining ground at roughly the same rate as students from more affluent schools.

But the average student in grades three to eight is still 5 to 10 percentile points behind where students in those grades were in math three years ago. In reading, students are now 2 to 4 percentile points behind where students were three years ago.

And progress has been so slow that if improvement continues at the current pace, it could take a minimum of five years for students in middle school to regain lost ground, meaning they’ll head to college less prepared, Lewis said.

“We are running out of time, and if we continue to improve at this pace we’re not going to meet all of the needs of kids,” Lewis said.

She called on schools to offer more tutoring and to support teachers in adapting lessons to meet the needs of each student.

“Right now is not the time for a one-size-fits-all approach to recovery,” Lewis said. “We need to make sure we are meeting students’ needs proportional to the magnitude of those needs and offering supports and interventions that take into account how much ground there is to be gained overall.”