Coal’s other dark side: Toxic ash that can poison water and people

Workers who cleaned up a huge spill from a coal ash pond in Tennessee in 2008 are still suffering—and dying. The U.S. has 1,400 ash dumps.

On December 22, ten years to the day after a dike ruptured at a Tennessee Valley Authority power plant near Kingston, Tennessee, pouring more than a billion gallons of toxic coal ash into the Emory River, TVA took out a full-page ad in the local paper to congratulate itself and its contractors on a cleanup job well done. That same day, about 150 of the workers who actually cleaned up the spill gathered at the site, which is now a park with hiking trails, boat ramp, and ball fields. Standing in blue jeans and work boots near a homemade wooden cross, they commemorated a different aspect of the cleanup: their 36 coworkers who’ve died from brain cancer, lung cancer, leukemia, and other diseases.

Some of the survivors walked with canes. Most bore blisters from the arsenic buried in their skin. Nearly all carried inhalers in their pockets. TVA's ad did not mention them.

More than 200 cleanup workers and family members are now suing TVA's main contractor, Jacobs Engineering, for refusing to provide them with protective equipment and for causing their debilitating and in some cases deadly diseases. Last November they won the first phase of the trial: A federal jury agreed that Jacobs had failed to protect them and that exposure to coal ash could have caused their illnesses.

While the world focuses on coal's carbon-dioxide emissions, which are a leading driver of climate change, the Kingston spill and its aftermath highlight a far more immediate problem: What to do with the millions of tons of coal ash piled up in 1,400 unlined landfills and ponds around the U.S. Most of those dumps lie near lakes or rivers or above freshwater aquifers that supply drinking water to nearby communities.

The 5.4 million cubic yards of sludge that broke through a 57-foot earthen dike at Kingston was the largest industrial spill in the nation's history—nearly ten times the size of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill two years later in the Gulf of Mexico. The wave of wet ash smothered some 300 acres around the plant and dozens of houses in the small community of Swan Pond, before turning several miles of the Emory, Clinch, and Tennessee Rivers, as well as parts of the Watts Bar Reservoir into a lumpy gray chowder.

TVA's Kingston Fossil Plant, built in 1955, was the largest coal-burning power plant in the world for more than a decade, and it still burns 14,000 tons of pulverized coal, or 140 rail-car loads, each day. About 10 percent of the coal, the non-combustible part, becomes coal ash—powdery fly ash that collects in smokestack filters, and coarser bottom ash and boiler slag that gets flushed out of the plant's furnaces. The ash is a mix of clays, quartz, and other minerals, forged into tiny glass-like beads by the heat of the fire.

But it also concentrates dozens of naturally occurring heavy metals, including known carcinogens and toxins such as arsenic, cadmium, lead, vanadium, chromium, as well as radioactive uranium and radon. These metals pose the greatest health threat from coal ash. Even without a catastrophic spill, they can leach into and contaminate groundwater. Attached to fine particles of ash they can drift through the air, blowing onto skin and into nostrils.

Some coal ash particles are so fine—less than 2.5 microns in diameter, a 30th the width of a human hair—that they can be sucked deep into the lungs and become a health hazard even without toxic hitchhikers. PM 2.5, as such particles are called, are also in smog, smoke, and auto exhaust, and they’re a known cause of numerous respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and a significant cause of global mortality.

"TVA has given my husband a death sentence," says Janie Clark, whose husband Ansol Clark built the cross for the memorial this past December. "They gave him an incurable blood disease and destroyed his heart. Coal ash is a dirty dark secret that has gone on in this state and this country way too long. It needs to be brought to light."

Safe as sand?

Utilities have long maintained that coal ash is as safe as sand (which is mostly silicon dioxide, and far coarser than ash) and that its trace concentrations of toxins are not much higher than background levels in the soil.

"In your backyard you may have 20 to 50 parts per million (ppm) of arsenic depending on where you live," says John Kammeyer, TVA's vice-president for civil projects, who was in charge of engineering for the cleanup. "You don't eat the dirt in your backyard because there's arsenic in it. Drinking water standards are about ten ppm. In the coal ash at Kingston it's 70 ppm, but there's no evidence that any of this got into drinking water. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, EPA, and Vanderbilt all tested the birds and fish to see if there was any impact. They concluded we didn't do any harm."

The Kingston cleanup workers, however, were heavily exposed to airborne ash. More than 900 people worked on the site between 2008 and 2015, operating the giant dredges, track-hoes, bulldozers and other earth-moving equipment to remove the ash from the river, dry it in windrows, and ship it in rail cars to a lined landfill near Uniontown, Alabama.

Ansol Clark was one of the first to arrive at the site on December 22, 2008. A 57-year-old professional truck driver, he’d just gotten a clean bill of health on his Department of Transportation physical. For the next five years he worked as a fuel-truck driver at the site, putting in 15-hour days, often seven days a week, keeping the big earth-moving machines running.

After two years he started having breathing problems, runny nose, and coughing. Then he started getting dizzy spells. One day he got up to go to work and collapsed on the bedroom floor.

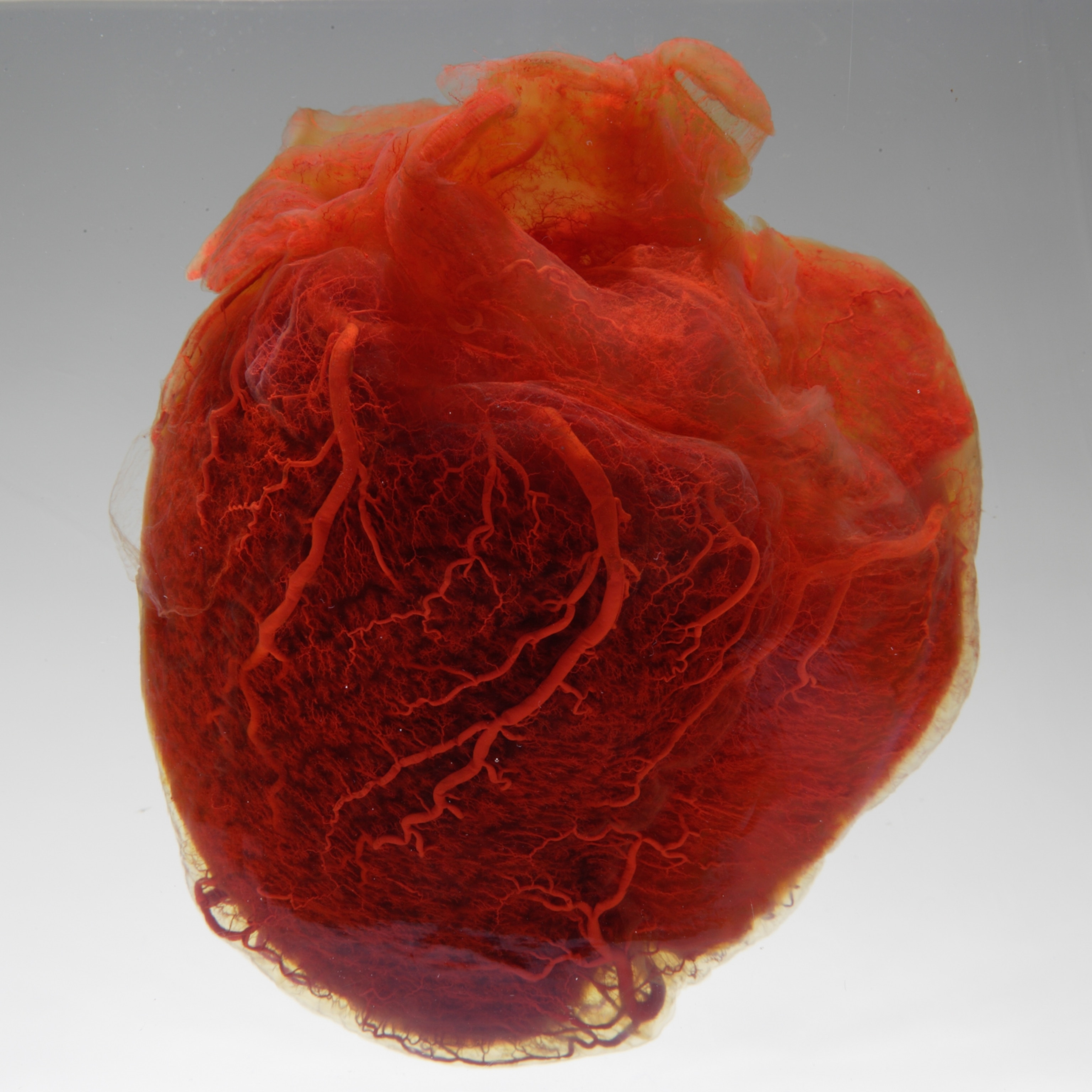

The doctors told him he had arrhythmia, that his heart wasn't getting enough oxygen. They gave him medicine, and he went back to work. Then he started having black-out spells. Eventually he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. A few months after he was forced to quit, he suffered a massive stroke. He recovered, but has since been diagnosed with polycythemia vera, a rare blood cancer. His doctors say it was likely caused by radiation from the ash.

"After Jacobs took over [the cleanup] at three months, they started telling us everything was safe," says Clark, who is now 67. "And we worked in a blue haze for months. When we started piling it up and the dust started blowing, they said it was pollen. Take an allergy pill and you'll be fine in a week. They'd tell us you can eat a pound of it every day and it won't hurt you."

Several of Clark's coworkers had similar experiences. Frankie Norris of Albany, Kentucky, was 47 when he began driving bulldozers, track-hoes, and fuel trucks at the site. After six months he began having trouble using the bathroom. His blood pressure spiked, and he got burning sores on his skin. After four years he was laid off for his illnesses. In 2016 his colon ruptured, sending him into the ICU for 19 days, where he almost died.

"Was it dusty? Lord yes," says Norris. "Every time those air brakes went off it'd blow dust in your face. I was in dust constantly for 10 to 12 hours a day. I went up with some other guys and we asked for dust masks. They told us there wouldn't be no dust masks. Safety guy told us we'd get fired for even asking for one."

Norris says he thought about quitting, but he had a wife and three kids to support. It was the depths of the recession, and the cleanup jobs paid more than $20 an hour. There were men standing in line for them.

"I needed the work," Norris said. "I wanted to get my kids through school. But I didn't expect TVA to kill us."

On the front line, but forgotten

TVA, which is a federal agency, is not currently involved in the workers’ lawsuit against Jacobs Engineering, although it may be on the hook for its contractor's legal fees, according to its own 2018 annual report. During the trial, several epidemiologists testified to the health impacts of the constituents of coal ash. According to Barry Levy of Tufts University, a leading expert in environmental health, just six of the toxins in Kingston's coal ash-—fine particulates, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, vanadium and naturally occurring radioactive materials—could cause many of the worker's illnesses.

"These hazardous substances are well established as causing a wide variety of adverse health effects in humans," Levy wrote in his report, "including cancer, respiratory disorders, neurologic disorders and various other diseases."

Arsenic alone, for example, has been shown to cause lung cancer, bladder cancer, and skin cancer, among many other diseases experienced by the cleanup workers. The combination of toxins may also be more dangerous than any single one alone, according to Levy. There are more than 20 toxins in Kingston's coal ash.

Court documents show TVA and Jacobs asking EPA to lower worker-safety standards; hidden video taken by the workers show company representatives tampering with personal air monitors and testing equipment. All that evidence suggests there was a concerted effort by TVA and Jacobs to downplay the dangers of coal ash, says Jamie Satterfield, an investigative reporter for the Knoxville News-Sentinel who has covered the story extensively over the years. The motive, she says, was to reassure the public that coal ash wasn’t a threat.

"It was a PR thing," says Satterfield. "The public was mad as hell. There were lots of public meetings, with parents asking, 'Are my kids in danger?' TVA sent a clear command to Jacobs: First, no coal ash on any trucks or equipment leaving the site; so they built a million-dollar car wash. Second, no one in respirators or Tyvek suits. The manager for Jacobs told people not even to wear dust masks.

"These are hard-working, blue-collar, decent people," says Satterfield, who has interviewed hundreds of cleanup workers. "They knew nothing about the dangers. After the spill everybody came in, senators, the environmental groups, all worried about the impact on the community, walking right by these workers in T-shirts and no protective gear who were working in the coal ash day in, day out. No one was paying attention to them."

Neither TVA officials nor Jacobs Engineering would comment on the ongoing litigation, although in court Jacobs denied any wrongdoing. TVA's Kammeyer also denied any concerted effort to downplay the danger of coal ash. "I know of no [PR] campaign," he says. "My engineers put cameras up to monitor it and make sure we were meeting our standards for air quality, keeping the dust down. So I know we were doing all the right things."

TVA has refused to release any video footage of the worksite, although local environmental activists captured video of at least one major dust storm at the cleanup in 2009. TVA's own independent inspector general, Richard Moore, slammed the agency for avoiding transparency and accountability as part of its legal strategy after the spill. Moreover, in a 111-page report on the cause of the spill released in 2009, Moore blasted the agency for "irresponsible coal ash practices" that led to numerous seeps and breeches in its ash ponds dating back to 1980.

A nationwide problem from hell

TVA isn't the only utility with an ash problem. In February 2014, a storm drain at a 50-year-old ash pond owned by Duke Energy collapsed near Eden, North Carolina, disgorging 39,000 tons of ash and 27,000 gallons of polluted water into the Dan River. Only a fraction of the ash was recovered, and contaminants were detected 70 miles downstream. Last year Hurricane Florence flooded two other Duke ash ponds in eastern North Carolina, resulting in smaller releases.

Such disasters are thankfully rare, but researchers say the greater issue is the sheer ubiquity of coal ash around the nation. Though its share of the fuel mix is declining, coal still generates nearly 30 percent of the electricity in the United States, creating more than 100 million tons of ash each year—the largest industrial solid waste stream in the country. There are more than 1,000 active coal ash landfills and ponds in the United States, and hundreds of retired ash dumps. Most are unlined holes in the ground.

Roughly 60 percent of coal ash is recycled, according the American Coal Ash Association (ACAA), generating about $23 billion in revenue each year for utilities. Most goes into concrete and cement, but ash has also been used in roadbeds, as fill under housing developments and golf courses, even for snow control or as fertilizer on agricultural land.

After the Kingston spill, environmental groups advocated regulating coal ash as hazardous waste. But the utilities and ACAA lobbied hard against the move, arguing that it would dry up the market for recycling and just create more coal ash. EPA instead passed its first regulation on coal ash storage, requiring that all new coal ash landfills be lined (although existing unlined landfills can still be used), and that companies test groundwater around the ash ponds.

The industry-generated data were released last March: They revealed groundwater contamination at 95 percent of the tested sites. The utilities are required to retest, then clean up the contamination and even close the site if it continues. The Trump Administration is now attempting to roll back those regulations as too burdensome, allowing states to end groundwater monitoring and other requirements.

"It's not just one toxin," says Avner Vengosh, a geochemist at Duke University who studied both the Kingston and Dan River spills. "It's a cocktail of arsenic, copper, lead, selenium, thallium, antimony, and other metals at higher levels than in their natural state. People think coal ash is not going to be a problem because utilities are switching to natural gas and it's cleaner. But the legacy of coal ash production and disposal is going to be with us for ages. These contaminants don't biodegrade."

For Jeff Brewer, 44, of New Market, Tennessee, he and his coal-ash coworkers were little more than expendable guinea pigs. He started working on the Kingston cleanup as a healthy man in his mid-30s, and after four years in the pit he was on two blood-pressure pills, a fluid pill, and a steroid inhaler; he was getting a testosterone shot every two weeks. He's been diagnosed with liver dysfunction and obstructive lung disease. Every few minutes he's racked by a harsh barking cough.

"It was like sucking the life out of you," Brewer says. "If I knew what I know today, I'd have picked up cans on the side of the road. But I had a wife and three girls and I needed to provide for them. And they told us it wouldn't hurt us. You could eat a pound of it every day."

While the Kingston workers' exposure was extreme, they were the canaries in the coal-ash mine. Until all the ash ponds and landfills are cleaned up—and we stop burning coal—the risk to U.S. drinking water supplies remains. The next phase of the Kingston trial, in which individual workers will attempt to prove their illnesses were caused by coal ash exposure, will begin later this year.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital