U.S. support for Israel at the U.N. is in jeopardy, White House says

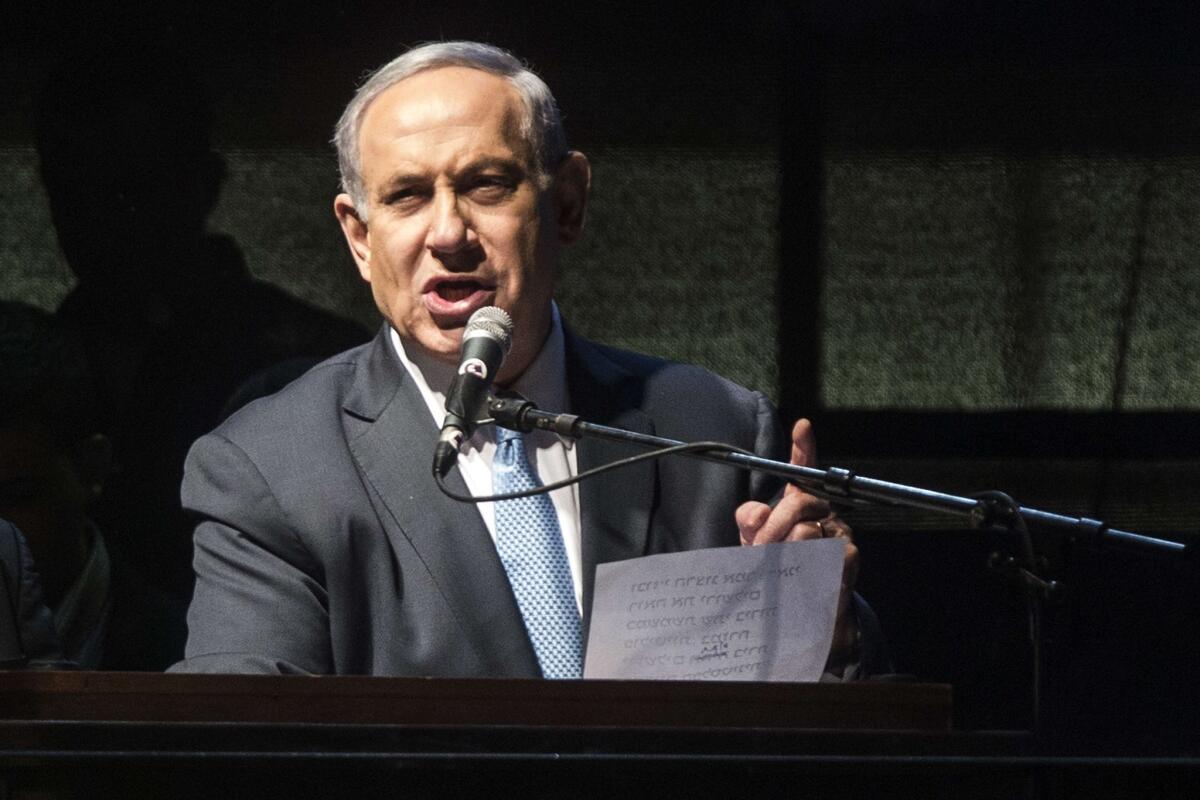

The White House on Wednesday pointedly criticized Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s successful reelection campaign and suggested his newly declared opposition to a Palestinian state could jeopardize America’s unwavering support for Israel at the United Nations.

The blunt comments by Obama administration officials illustrated how the campaign tactics Netanyahu used to win an unexpectedly strong victory in Tuesday’s election have further strained the historic ties between the United States and Israel. After six years of tension, relations between the two governments have frayed to a point not reached in decades.

Netanyahu made opposition to U.S. nuclear negotiations with Iran a centerpiece of his reelection effort. Then, in the closing days of the campaign, he said he would never agree to a sovereign Palestinian state, repudiating the concept of a two-state solution that has been a central element of U.S. policy under Presidents Obama and George W. Bush.

The Israeli leader had said in a major address in 2009 that his “vision of peace” included “two free peoples” living side by side in separate, independent states for Israelis and Palestinians. Many U.S. officials, as well as most Arabs, had questioned his sincerity, but Netanyahu’s public reversal this week nonetheless marked a significant shift that administration officials rebuked Wednesday.

The U.S. would “reevaluate our approach” based on Netanyahu’s “change in his position,” White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest told reporters as the president flew to Cleveland to deliver a speech on economic policy.

State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki raised the possibility that the reevaluation could include a shift in position at the U.N. She avoided the usual U.S. language about vetoing Security Council resolutions that Israel opposes.

“The prime minister’s recent statements call into question his commitment to a two-state solution,” Psaki told reporters. “We’re not going to prejudge what we would do if there was a U.N. action.”

Earnest also went out of his way to criticize one of Netanyahu’s final campaign tactics: a videotaped warning to supporters that “Arab voters are streaming in droves” to the polls.

The United States was “deeply concerned about rhetoric that seeks to marginalize Arab-Israeli citizens,” Earnest said, even though reporters had not asked him about the U.S. reaction. “It undermines the values and democratic ideals that have been important to our democracy and an important part of what binds the United States and Israel together.”

Secretary of State John F. Kerry, who is deeply involved with the Iran negotiations, called Netanyahu from Switzerland on Wednesday to congratulate him, Earnest said. Obama has not done so, but would at some point, the press secretary said.

A senior administration official, speaking on condition of anonymity in accordance with White House policy, said that U.S. officials understood Netanyahu’s “need to tack to the right” during his campaign. “We get that those are tactics,” the official said.

But, the official added, referring to the prime minister by his nickname, “Bibi needs to understand that there are policy ramifications for the way he did this. You can’t say all this” about rejecting the two-state policy “and then just say, ‘I was just kidding.’”

Moreover, the official said, Netanyahu’s comments about Arabs voting “made people recoil.”

Obama in particular found the comments disturbing, a second senior official said.

Both on substance and rhetoric, the new Israeli government will be on a “collision course” with the United States as well as major European countries, said Itamar Rabinovich, who served as Israel’s ambassador to Washington under Labor party governments during the mid-1990s.

Whether the two longtime allies can step back from such a collision — or even want to — will start to become apparent as Netanyahu negotiates to form a new governing coalition and U.S. officials decide how to respond to him.

Israel has often brought its influence to bear quietly, in private conversations with members of Congress and other top U.S. officials about security threats. Israeli officials could get to U.S. policymakers early, using assessments from their intelligence agencies to help steer American decisions.

Some of that trust and access will now be lost, former U.S. officials said.

Informal contacts have “been one of the most effective ways Israel has gotten what it wants,” one former official said, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss relations with a key ally. “It won’t be the same.”

Already, in recent weeks, U.S. officials announced publicly that they were limiting how much information they would share with Israel about the nuclear negotiations with Iran. Netanyahu’s government was using the data to denounce the American bargaining position in the talks, they said, accusing the Israelis of selective and misleading leaks.

If negotiators actually reach a deal with Iran, that probably will lead to further tension. Netanyahu made clear in his speech to Congress on March 3 that he would oppose a deal, and he may use Israeli intelligence estimates to challenge the U.S. assessment of how a deal would prevent an Iranian nuclear breakout.

Martin Indyk, who led the Obama administration’s last effort to broker an Israeli-Palestinian peace, said recently that if the new Israeli government didn’t resume peace negotiations with the Palestinians, the administration might join the other four permanent members of the U.N. Security Council in adopting a resolution laying out key principles for a peace settlement.

Such a move would be jarring to Israel, which has counted on steadfast American defense at the U.N. and doesn’t want international bodies intervening in negotiations.

Politics on both sides amplify the diplomatic tension.

Under Netanyahu, the conservative Likud party has become more closely identified with America’s Republican Party, sharing political consultants and some major financial backers, most notably Sheldon Adelson, the Las Vegas casino billionaire. Evangelical Christians, who are a major constituency for the Republicans, also strongly back Netanyahu’s policies, according to opinion polls.

Democrats, meanwhile, have been closely identified with parties in Israel’s center and left that oppose Netanyahu. Major Democratic constituency groups, including the majority of American Jews, have been critical of the prime minister, particularly over his disinclination to negotiate with the Palestinians.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) reflected the Democratic view in a statement Wednesday, saying that “Israel must pursue a negotiated two-state solution with the Palestinians,” precisely what Netanyahu appeared to rule out over the weekend.

“This is the only way to ensure Israel remains a secure, Jewish, democratic state,” Feinstein said.

At the same time, most of America’s support for Israel has strong bipartisan backing, which is not likely to change. The United States provides Israel $3.1 billion in annual military aid, vital intelligence support and works to assure that Israel has better military gear than any of its regional adversaries.

The administration will also continue to defend Israel diplomatically on many fronts, as it has even during the recent weeks of strife, officials emphasized. In Wednesday’s statements, for example, Psaki reiterated that the U.S. would continue to try to block Palestinian efforts to join the International Criminal Court.

Some Netanyahu allies are predicting that the new government and the United States will cooperate to some extent in trying to stabilize the conflict with the Palestinians at a moment when the Palestinian Authority is near collapse.

But the process of building a new coalition government in Israel could also lead to more conflicts. Netanyahu is likely to approve continued expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, for example, something he promised conservative supporters during the campaign. That would put him directly at odds with the administration.

Prospects for peace negotiations seem “bleak,” said Rabinovich, the former ambassador, who is also a historian.

Over the years, successful peace deals have required three ingredients: a conservative Israeli prime minister ready to make a deal, a Palestinian leader willing to compromise and a U.S. administration with a clear Mideast policy.

“Right now,” Rabinovich said, “we might not have even one in place, certainly not all three.”

Lauter reported from Washington and Richter from Lausanne, Switzerland. Times staff writers Laura King in Tel Aviv, Michael A. Memoli in Cleveland and Christi Parsons and Edmund Sanders in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.