Resilience for the Future: The UK’s Critical Minerals Strategy

Updated 13 March 2023

Foreword from the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Almost every part of modern daily life relies on minerals, often mined thousands of miles away.

From our cars to mobile phones, wind turbines to medical devices, modern society is quite literally built on rocks.

As technology evolves faster than ever, we become more and more reliant on a new cohort of minerals. We are moving to a world powered by critical minerals: we need lithium, cobalt and graphite to make batteries for electric cars; silicon and tin for our electronics; rare earth elements for electric cars and wind turbines.

Critical minerals will become even more important as we seek to bolster our energy security and domestic industrial resilience – in light of Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine – and as we move away from volatile, expensive fossil fuels.

The world in 2040 is expected to need 4 times as many critical minerals for clean energy technologies as it does today[footnote 1].

However, critical mineral supply chains are complex and opaque, the market is volatile and distorted, and China is the dominant player. This creates a situation where UK jobs and industries rely on minerals vulnerable to market shocks, geopolitical events and logistical disruptions, at a time when global demand for these minerals is rising faster than ever.

It is vital that we make our supply chains more resilient and more diverse to support British industries of the future, deliver on our energy transition and protect our national security.

This government is taking action to ensure we remain in the game.

The UK’s first ever Critical Minerals Strategy sets out our plan to secure our supply chains, by boosting domestic capability in a way that generates new jobs and wealth, attracting investment and playing a leading role in solving global challenges with our international partners.

Through the Strategy, we will:

- accelerate growth of the UK’s domestic capabilities

- collaborate with international partners

- enhance international markets to make them more responsive, transparent and responsible

The UK has pockets of mineral wealth from the Scottish Highlands to the tip of Cornwall, and clusters of expertise in refining and material manufacturing. The UK’s mining and minerals history runs deep, dating back to the Bronze Age. In most mines today, it is said you can usually find someone who has trained at the world-renowned Camborne School of Mines – such is the UK’s historical strength.

We will maximise what the UK produces along the critical minerals value chain – through mining, refining, manufacturing and recycling – in a way that creates jobs and growth and protects communities and our natural environment. We will re-establish the UK as a skills leader and continue to do cutting-edge research and innovation in exploration, mining, refining and manufacturing.

The Strategy sets out our ambitions to work with other countries to strengthen trading and diplomatic relationships, and efforts to make supply chains more diverse, transparent, responsible and resilient. This will create opportunities for UK companies overseas and make sure UK businesses are trading on a level playing field.

From the iron and coal that put the UK at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution, to the critical minerals essential to the new, Green Industrial Revolution: the UK once was – and will now be again – a leading player in the global race for critical minerals.

This Strategy will help create the more secure, more resilient supply chains needed for a clean, safe and prosperous future.

The Rt Hon Kwasi Kwarteng

Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Accelerate, Collaborate and Enhance: Our New Approach to Critical Minerals

In a challenging world, the UK’s new critical minerals strategy intends to improve the resilience of critical minerals supply chains. It aims to ensure that, in the decades to come, the minerals we will need to power our world in the future, can be made available in the quantities needed, extracted in responsible ways and supported by well-functioning and transparent markets. And, in doing that, we want to position the UK at the forefront of the green industrial revolution, create opportunities for UK businesses, and take opportunities to level up, innovate and tread more lightly on the earth – all whilst showing international leadership.

This strategy sets out how we will do this through our new A-C-E approach. We aim to:

Accelerate the UK’s domestic capabilities

1. Maximise what the UK can produce domestically, where viable for businesses and where it works for communities and our natural environment.

2. Rebuild our skills in mining and minerals.

3. Carry out cutting-edge research and development to solve the challenges in critical minerals supply chains.

4. Make better use of what we have by accelerating a circular economy of critical minerals in the UK – increasing recovery, reuse and recycling rates and resource efficiency, to alleviate pressure on primary supply.

Collaborate with international partners

5. Diversify supply across the world so it becomes more resilient as demand grows.

6. Support UK companies to participate overseas in diversified responsible and transparent supply chains.

7. Develop our diplomatic, trading and development relationships around the world to improve the resilience of supply to the UK.

Enhance international markets

8. Boost global environmental, social and governance performance (ESG), reducing vulnerability to disruption and levelling the playing field for responsible businesses.

9. Develop well-functioning and transparent markets, through improved data and traceability.

10. Champion London as the world’s capital of responsible finance for critical minerals.

Why do we need a strategy? Why now?

The world has relied upon critical minerals, often extracted from remote parts of the world and made available through complex and challenging supply chains, for many decades. Vanadium had its first key industrial application in the steel alloy chassis of the Ford Model T at the turn of the twentieth century. Lithium was helping to lubricate fighter aircraft in World War II. Tin has been mined by humans and used in bronze and other alloys for over 5,000 years.

Our reliance upon critical minerals is by no means new. Yet, in recent years, their importance has taken on a new salience. Technological change – for example, in electronics, energy generation, transport and military equipment – means we will require large amounts of minerals that are currently only available in small quantities.

Over time, critical minerals have become more and more embedded in our daily life. Almost everything we do to communicate, to get around, to work and to play is increasingly based, directly or indirectly, on minerals extracted from the ground many thousands of miles away.

Countries’ climate change ambitions are changing the way we produce, distribute and store energy. Clean energy technologies – such as electric cars, wind turbines, photovoltaics, hydrogen production and nuclear reactors – will need to be deployed quickly. The UK currently relies on complex and delicate global supply chains for its rapidly growing demand for critical minerals to fuel its net zero future[footnote 2]. Seven of the government’s Ten Point Plan targets for a green industrial revolution assume a stable supply of critical minerals[footnote 3].

Global demand for electric vehicle battery minerals (lithium, graphite, cobalt, nickel) is projected to increase by between 6 and 13 times by 2040 under stated policies[footnote 4], which exceeds the rate at which new primary and secondary sources are currently being developed. The UK’s automotive and electric vehicle battery ecosystem, as an example, could grow by 100,000 jobs by 2040 but depends on the development of a UK battery manufacturing capability. Our intention to build a new generation of gigafactories will only happen in the UK if there is a resilient supply of battery minerals[footnote 5].

As well as underpinning our energy transition and key manufacturing industries, critical minerals also underpin our national security. The UK’s ability to deploy cutting-edge military capability – whether land, air, sea, space or cyberspace – is dependent on strategic materials, including critical minerals. Critical minerals are found in military systems ranging from the simplest firearm to F35 fighter jets and nuclear submarines. The quantities are relatively small, but high-purity, high-value materials are required. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) works with key suppliers to mitigate supply chain risks. Sustained disruption would over time reduce the UK’s freedom of action.

The importance of critical minerals to national security goes beyond military capability – foreign actors may use control of resources as leverage on other issues[footnote 6]. Former National Security Advisor, Lord Sedwill, recently noted that “critical minerals, semiconductors and data are the oil, steel and electricity of the 21st century.”[footnote 7].

For many decades, we have been able to rely on the market to provide our needs. British mining companies have prospected the world for new sources of minerals, mined them and traded them around the world. Exchanges such as those in the City of London have developed increasingly transparent markets in some commodities, which match supply and demand across the globe. Cutting edge research and development, both in the UK and abroad, has demonstrated new applications, improved efficiency and pushed boundaries – enabled by a global trading system.

For many minerals, that effective and efficient market is exactly what we will continue to rely upon and champion. Where the market already provides a responsible and resilient supply, we see no case to interfere. For those minerals where the market is functioning to the benefit of the UK, the job of government is to ensure that markets are protected for the long term from future distortions. And, for the remainder, where the markets are less developed, are less transparent or have issues, we want to work with business and international partners to make markets more resilient for the long term.

For critical minerals, a confluence of challenges and constraints put the UK’s security of supply at risk:

- Rapid demand growth and long lead times: Global demand growth for certain minerals, driven in many cases by decarbonisation targets, could outstrip supply chain capacity, which will struggle to expand quickly enough owing to long lead times for mine development and mineral processing. Rising demand has caused lithium prices to increase nearly 400 percent year-on-year, as of May 2022[footnote 8].

- By- / co-products: Critical minerals are often by-products or co-products of mining for other commodities, so supply and demand are disconnected.

- Geographical dominance: Extraction and processing are highly concentrated, which creates risks of supply constraints and price volatility in case of geopolitical events or disruption to logistics.

- State-sponsored activity: State-subsidised companies can operate globally with greater agility, at lower margins and with longer investment timeframes, creating a disadvantage for those not subsidised.

- Opacity and volatility: Critical mineral supply chains are complex. Data are of variable quality, consistency and accessibility. It is very difficult to trace supply of critical minerals from mine to end-product. Many critical mineral markets are “incomplete markets” because there is no organised market on which to trade. Recent history has shown how prices can be manipulated by those in control of supply. Volatility creates commercial risk and deters investors.

- Non-substitutability: Clean energy technologies, such as electric vehicle batteries, are stretching the limits of technical performance in the short-term, so rely on a technical optimum combination of materials. Pressure to substitute materials is likely to be detrimental to the development and adoption of the technology. Where substitution may be viable in the long term, it will not resolve short- and medium-term supply challenges.

- ESG issues: Supply chains are fraught with ESG issues and risks, which creates added vulnerability to disruption. The true cost of the negative externalities is not recognised in the price of the minerals. The market does not differentiate based on provenance and there is inconsistency in the definition of ESG standards. Responsible UK companies bear additional costs to do things the right way, putting them at a competitive disadvantage.

Recent global events – notably Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic and disruptions at global supply chain choke points – are causing short-term disruptions and price volatility for some commodities, including certain critical minerals.

But these events may also have longer-term effects. They underline the inherent risks in global supply chains. They highlight the need to know where products come from and for traceability. They are impacting geopolitical relationships, including with important critical mineral producer countries. Pressure on energy security may accelerate the transition to renewables and the demand growth for certain minerals. The situation further highlights the need for a robust strategy for the UK to improve the resilience of the supply of critical minerals.

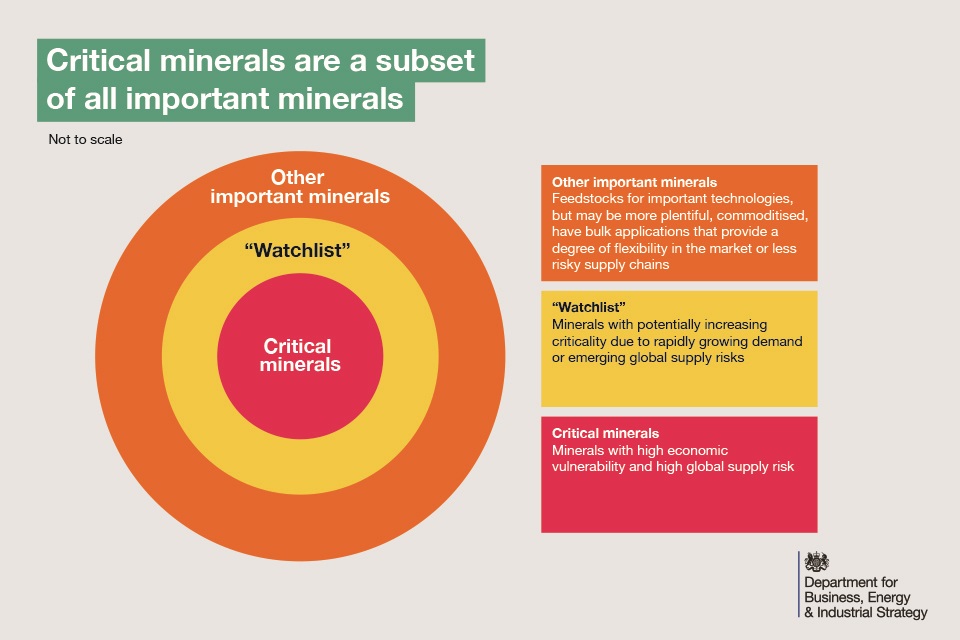

What is a critical mineral?

Modern economies rely on countless raw materials. Many minerals have important uses but, by dint of plentiful supply, functioning markets or an ability to substitute them, do not warrant the focus that others may at this stage. By necessity of focus, only some are defined as “critical”.

These ‘critical minerals’ are not only vitally important but are also experiencing major risks to their security of supply. These risks can be caused by combinations of factors including but not limited to rapid demand growth, high concentration of supply chains in particularly countries, or high levels of price volatility. Many of these critical minerals are produced in comparatively small volumes or as companion metals (imeaning they’re produced as by-products of other mining activities), are non-substitutable in their applications and have low recycling rates.

To underpin the long-term nature of this strategy, the UK will evaluate the criticality of minerals on an annual basis. This will be part of the function of the new Critical Minerals Intelligence Centre (CMIC), described later in this strategy, which will be led by the British Geological Survey (BGS). The assessment will be done through an impartial and evidence-based process, using a methodology agreed with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

Figure 1: Schematic of critical minerals, as a subset of all important minerals

To support the launch of this strategy, BGS has carried out its first criticality assessment and, according to economic vulnerability and supply risk, has defined a cohort of minerals with high criticality for the UK[footnote 9]:

- Antimony

- Bismuth

- Cobalt

- Gallium

- Graphite

- Indium

- Lithium

- Magnesium

- Niobium

- Palladium

- Platinum

- Rare Earth Elements

- Silicon

- Tantalum

- Tellurium

- Tin

- Tungsten

- Vanadium

As part of this process, the BEIS Critical Minerals Expert Committee[footnote 10] will also be asked to advise on a ‘watchlist’ of minerals that are deemed to be increasing in criticality. Such movement may happen very quickly in the event of an unexpected market or supply shock, or may happen over a longer period, due to evolving demand or supply trends.

The Critical Minerals Expert Committee’s first watchlist is:

- Iridium

- Manganese

- Nickel

- Phosphates

- Ruthenium

Nickel, for example, is traded in large global markets and has a diverse range of applications, giving supply chains a degree of resilience. However, Russia is a major supplier, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused significant disruption to nickel markets. Class 1 (high purity) nickel is an important metal for electric vehicle batteries, and as Russia continues its aggression in Ukraine, the criticality of nickel may rise over the coming year, hence its inclusion in the watchlist.

The overall intention within this approach is for the UK to have an evidence-based, clearly articulated and evolving list of critical minerals, which reflects the dynamic nature of global supply chains and mineral markets.

The UK’s objectives and approach

The UK has pockets of mineral wealth, and it will be important to develop our domestic resources in a way that works for communities and the environment. However, it is not possible (or even desirable) to onshore all aspects of critical mineral supply chains. No country has domestic access to all these resources and, consequently, we always will need to think internationally about our approach towards critical minerals.

At present, the UK largely relies on market forces to deliver a secure supply of minerals to UK industry. For much of our future mineral requirements, it is likely that the market will deliver at the scale we need. However, for some critical minerals, the market is not working effectively. Since the 1980s China has, through state intervention and subsidies, been building capabilities and establishing control of many critical mineral markets. Now other governments including Australia, Canada, Japan, the US and various European countries are accelerating efforts to secure their own supplies, and the UK needs a strategy to keep pace.

Consequently, our approach is based upon the UK leveraging its position of international leadership, including as home to global mining majors, as a centre of responsible mining finance, metals trading and standards, and as a major consumer of critical minerals in our advanced manufacturing industries. The UK has a heritage in mining and minerals, a plethora of mining equipment and services companies, and world-leading research and innovation on critical mineral extraction, processing and recycling. Building on centuries of expertise, we can re-position the UK as an innovation and skills leader. The UK also has a role as an international dealmaker, leveraging our expertise in regulatory diplomacy, our extensive engagement in multilateral forums and our strong relationships with mineral-rich producer countries and consumer markets.

This strategy aims – where possible and proportionate – to mitigate risks and to improve resilience of critical mineral supply chains, increasing confidence in the UK’s net zero transition, key manufacturing sectors and national security. In a challenging world, the UK’s new critical minerals strategy intends to build resilience, mitigate risks and collaborate internationally.

We will do this through our new A-C-E approach to critical minerals:

Accelerate the UK’s domestic capabilities

- 1. Maximise what the UK can produce domestically, where viable for businesses and where it works for communities and our natural environment.

- a) We will find out what critical minerals there are in the UK.

- b) We will signpost financial support that can accelerate the development of our capabilities.

- c) We will reduce barriers to domestic exploration and extraction of critical minerals.

- d) We will highlight the UK as a strategic location for refining and midstream materials manufacturing.

- 2. Rebuild our skills in mining and minerals.

- a) We will train the next generation of miners, geologists, engineers and beyond.

- b) We will support the development of industrial clusters.

- 3. Carry out cutting-edge research and development to solve the challenges in critical minerals supply chains.

- a) We will promote innovation and re-establish the UK as a centre of critical mineral and mining expertise.

- 4. Make better use of what we have by accelerating a circular economy of critical minerals in the UK – increasing recovery, reuse and recycling rates and resource efficiency, to alleviate pressure on primary supply.

- a) We will promote innovation for a more efficient circular economy for critical minerals in the UK.

- b) We will signpost financial support to accelerate the development of a UK critical mineral circular economy.

- c) We will look at regulatory ways to promote recycling and recovery.

- a) We will promote innovation for a more efficient circular economy for critical minerals in the UK.

Collaborate with international partners

- 5. Diversify supply across the world so it becomes more resilient as demand grows.

- a) We will support efforts to diversify international critical mineral supply chains.

- b) We will find out more about deep-seabed minerals and assess the challenges and opportunities of extracting them.

- 6. Support UK companies to participate overseas in diversified, responsible and transparent supply chains.

- a) We will support UK companies to participate in building responsible, diversified supply chains overseas.

- 7. Develop our diplomatic, trading and development relationships around the world to improve the resilience of supply to the UK.

- a) We will engage with key countries bilaterally on critical minerals, to promote joint working towards solutions to global issues in critical mineral value chains.

- b) We will continue to build plurilateral and multilateral partnerships to tackle global issues.

- a) We will engage with key countries bilaterally on critical minerals, to promote joint working towards solutions to global issues in critical mineral value chains.

Enhance international markets

- 8. Boost global environmental, social and governance performance (ESG), reducing vulnerability to disruption and levelling the playing field for responsible businesses.

- a) We will play a leading role in global efforts to drive up ESG performance to improve resilience of supply chains and level the playing field for responsible UK business overseas.

- b) We will role model standards for sustainable development of resources in the UK.

- 9. Develop well-functioning and transparent markets, through improved data and traceability.

- a) We will find out where critical minerals are produced, how they are traded and where they are used – both now and in future.

- b) We will make global markets function more effectively and be more transparent.

- c) We will promote innovative techniques to help UK companies trace where minerals are from.

- 10. Champion London as the world’s capital of responsible finance for critical minerals.

- a) We will position the UK as a centre of responsible international mining.

Many policy measures already exist to support these objectives. This strategy highlights them and focuses on maximising their impact for critical minerals. There is also a need for targeted new policy measures. This strategy sets out plans to develop new measures over the course of this parliament.

The UK has limited natural resources and depends on relatively concentrated, opaque global supply chains. Instead of aiming for self-sufficiency, our intention is to improve UK manufacturers’ access to critical minerals – either domestically or internationally – and ensure UK businesses benefit from the growth of global demand. We will use a suite of policy levers to promote a more resilient global supply chain, including through diversification, international partnerships and the circular economy.

We will be pragmatic in our approach, recognising some countries will not share UK values or ambitions for a diverse and transparent system. We will focus on building capabilities in collaboration with countries that share our ambitions and engaging constructively with others, while protecting our national security and values.

We ultimately aspire to support diverse, functioning and transparent markets for critical minerals. We recognise that may take years or even decades, depending on the mineral, and will seek to intervene in collaboration with global partners to accelerate progress towards this goal.

Some of the interventions described in this strategy will see immediate impacts, while others will reap benefits in the longer term. Interventions should be proportionate and not seek to over-regulate, create large burdens for businesses or hinder innovation, and will be in line with our commitments under the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

This strategy considers issues affecting security of supply of critical minerals along the full extent of the value chain: spanning exploration, extraction, refining, materials manufacture, and component and end-product manufacturing. It also recognises the role of recovery, recycling and reuse of critical minerals and components in alleviating pressure on primary demand.

Supporting government priorities

The strategy will support the Levelling Up agenda (as described in the Levelling Up White Paper)[footnote 11], helping to drive up pay, employment and productivity, particularly in industrial areas, such as Cornwall, Teesside, Merseyside, the Humber, Northern Ireland and Scotland.

It helps position the UK as a Scientific Superpower, through game-changing R&D on clean mining, geological mapping, recovery and recycling, and solutions to ESG issues and risks.

A resilient supply chain of critical minerals will support manufacturing of clean technologies in the UK – including zero emission vehicles. This will ensure the UK maximises the benefits from the transition to Net Zero and supports tens of thousands of high-quality green jobs across the UK.

It will draw on our expertise in regulatory diplomacy and put Global Britain into action.

A more secure supply of critical minerals will also support our Energy Security, National Security and wider Economic Security.

Engaging British industry and civil society

The government is engaging stakeholders to understand the challenges and opportunities that critical minerals supply chains present to UK industry. To support the development of this strategy, Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), in conjunction with other government departments, undertook a series of 11 roundtables with industry, academia and civil society between March and June 2022 on a wide variety of topics related to critical minerals, and attended a wide range of conferences and other events. Plans for ongoing engagement are under development.

Accelerate growth of domestic capabilities

Domestic production

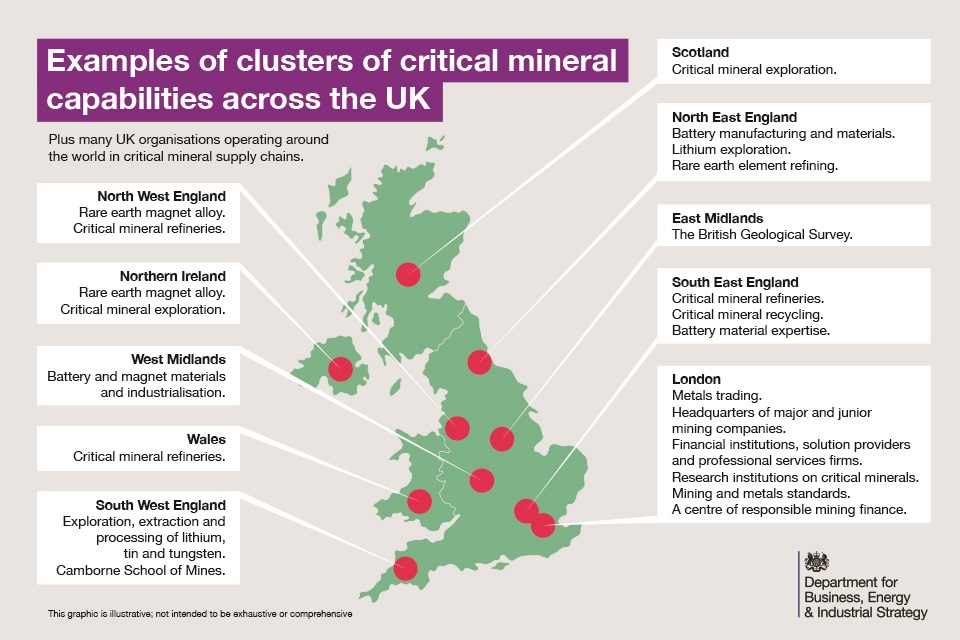

We want to create an enabling environment for companies to develop critical mineral capabilities in UK, including exploration, extraction, refining, materials manufacturing, recovery and recycling. These industries will create new employment opportunities and contribute a financial boost to local economies across the country. The UK has pockets of mineral wealth, and it will be important to develop our domestic resources and do so in a way that works for our economy, local communities and our natural environment. The UK has promising projects in lithium, tin and tungsten extraction, and growing capabilities for refining several other critical minerals. Clusters of expertise are developing across the country – as shown in Figure 2 – for example in the manufacture and recycling of rare earth permanent magnets.

Case study: Building a UK battery supply chain

As part of the Prime Minister’s ‘Ten Point Plan for a green industrial revolution’, the Government announced the end of the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030, with all new cars and vans being fully zero emission from 2035. The government has been working to encourage greater private investment into the UK’s zero emission vehicle supply chain. Battery manufacturing capacity will be an important component, alongside other technologies such as hydrogen fuel cells.

BEIS established the Automotive Transformation Fund (ATF) with the aim of developing a globally competitive electric vehicle supply chain. The ATF provides support for late-stage R&D and capital investment in strategically important technologies, including battery manufacturing.

We have already had success in securing investment. In July 2021, Envision AESC announced investment in a new gigafactory in Sunderland, which forms part of the £1 billion North East Electric Vehicle Hub that also includes investment by Nissan in electric vehicle manufacturing. In January 2022, it was announced that intended government support for Britishvolt’s gigafactory in Blyth, had unlocked £1.7 billion of private investment. Recent investment by Stellantis and Bentley in electric vehicle manufacturing in the UK create further opportunities for the UK to continue to expand its battery manufacturing capabilities.

In March, government published its automotive investor roadmap, which shows how it will work with industry to maintain the UK’s leadership in zero emission vehicles. The roadmap will be used to support our work with business, investors and regulators to encourage investment into the UK automotive industry and its supply chain. Government is promoting opportunities for investment through its online tool, the Investment Atlas, as well as through dedicated investment promotion teams overseas. All this provides investors with a strong signal about the government’s intention to position the UK as the place to invest in zero emission vehicle manufacturing and its supply chain.

Figure 2: Examples of clusters of critical mineral capabilities across the UK (BEIS)

We will find out what critical minerals there are in the UK

- Begin a national-scale assessment of the critical minerals within the UK. By March 2023, we will collate geoscientific data and identify target areas of potential. This will lay the foundations for detailed field work – including airborne geophysical surveying – of target areas next year and catalyse commercial exploration.

- Develop our evidence base and understand the risks and potential for environmentally responsible extraction of minerals from coastal waters.

We will signpost financial support that can accelerate the development of critical mineral extraction, refining, processing and recycling capabilities.

- Explore how government funding mechanisms can support companies developing domestic critical mineral capabilities and reduce risk for investors in this field, where the market is not working or where we make a strategic choice to accelerate progress. Many mechanisms for financial support already exist and have already helped fund UK capabilities along the critical minerals value chain. We will signpost the most relevant funding support mechanisms to ensure they are easily identified, deployed effectively and can be accessed by the critical minerals sector.

- Use existing energy cost support schemes – and review opportunities for future support – for Energy Intensive Industries (EIIs) to support eligible companies in critical mineral value chains with energy costs.

- Develop an inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) proposition for UK critical minerals projects, building on the Department for International Trade’s (DIT) recent work in Cornwall.

Examples of financial support opportunities for UK critical minerals businesses

Eligibility for funding is specific to the conditions of the funds listed.

Automotive Transformation Fund (ATF) – Up to £850 million of funding is being invested in late-stage R&D and industrialisation projects to support development of an internationally-competitive zero-emission vehicle supply chain in the UK. Support is focused on strategically important technologies, including batteries, motors and drives, power electronics and hydrogen fuel cells. ATF is the automotive pillar of the Global Britain Investment Fund.

Industrial Energy Transformation Fund (IETF) – This £315 million fund helps businesses with high energy use – including eligible critical mineral companies – to cut their energy bills and carbon emissions through investing in energy efficiency and deep decarbonisation technologies.

National Security Strategic Investment Fund (NSSIF) – This fund acts as HM Government’s corporate venturing arm for dual-use advanced technologies, which is a joint initiative between the government and the British Business Bank. Its objectives include accelerating the adoption of the government’s future national security and defence capabilities and the development of the UK’s dual-use technology ecosystem.

Energy Intensive Industries (EII) schemes – There is support in place to reduce the cumulative impact of energy and climate change policies on industrial electricity prices for energy intensive industries – including eligible critical mineral companies. Schemes include exemption or compensation for a proportion of the indirect costs of funding the Contracts for Difference, renewables obligation and small-scale feed-in tariffs, and compensation for the indirect costs of the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS) and the Carbon Price Support (CPS) mechanisms.

The UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB) – The UKIB is a new, government-owned policy bank, focused on increasing infrastructure investment across the United Kingdom. It has £22 billion of financing capacity to deploy and is aiming to invest across the capital structure, including senior debt, mezzanine, guarantees and equity. Projects must meet the Bank’s investment principles of: supporting regional and local economic growth or helping to tackle climate change; being infrastructure assets or networks, or new infrastructure technology; delivering a positive financial return; and, crowding in significant private capital over time. The Bank’s first strategic plan highlighted that it will explore how it can support the development of supply chains across its five priority sectors (clean energy, transport, digital, water and waste).

UK Export Finance (UKEF) – As the UK’s export credit agency, UKEF offers a range of financial products to support export. UKEF products can support eligible critical mineral projects, including UK-based projects with potential to export or overseas projects that present opportunities for export of UK goods and services.

Funding success for critical minerals

Britishvolt received government support through the Automotive Transformation Fund (ATF) to develop a gigafactory in Blyth and will become a major consumer of battery materials such as lithium, graphite and cobalt. This project will support 3,000 direct jobs, and a further 5,000 in its supply chain. Britishvolt is also working with mining major Glencore to develop an ecosystem for battery recycling in the UK.

Less Common Metals, a UK-based rare earth magnet alloy manufacturer, was awarded funding by the ATF to conduct a feasibility study for a fully-integrated supply chain for rare earth permanent magnet production in the UK.

Pensana has received support from the ATF to develop a facility for industrial-scale separation of rare earth elements at Saltend Chemicals Park in the Humber Freeport. Rare earth oxides will be used in the manufacture of electrical vehicle motors and wind turbine generators. It will create 126 new jobs.

Green Lithium secured a grant from the ATF to support development activity around its plan to build and operate Europe’s first large-scale lithium refinery, located in the UK.

Cornish Lithium received investment through the government’s Getting Building Fund for construction of its geothermal lithium recovery pilot plant near to Redruth, as well as ATF funding for a scoping study for its hard rock project at Trelavour.

Weardale Lithium Limited received a grant from the ATF to support exploration and development activity as part of its feasibility study for extracting lithium from geothermal brines in County Durham.

We will reduce barriers to domestic exploration and extraction of critical minerals

- Use the current programme of planning reforms to deliver improvements across the planning system as a whole, including when planning for critical minerals. Continue engagement on matters affecting critical minerals as the planning reforms progress, including on the possible safeguarding of future critical mineral resources, exploration, development, mineral refining/processing, and associated infrastructure. Devolved administrations and local authorities will be engaged appropriately in this process.

- Review mineral rights-related barriers to exploration and extraction of critical minerals and explore ways to improve the accessibility of mineral rights information to expedite critical mineral mine development.

We will highlight the UK as a strategic location for refining and midstream materials manufacturing

- Highlight the advantages of Freeports, Industrial Clusters and support for Energy Intensive Industries (EIIs) for locating critical mineral refining and manufacturing activity in the UK.

- Assess how new Rules of Origin legislation can incentivise the development of local battery supply chains. The Rules of Origin for Electric Vehicle batteries agreed between the UK and the European Union (EU) are designed to encourage investment in the battery supply chain. The rules are staged over a period of seven years and require greater UK and EU content over time, giving manufacturers time to develop their supply chains. This may incentivise companies to develop UK capability in mineral refining and material manufacturing for the battery supply chain.

Skills

Production, stewardship and use of critical minerals needs a wide range of skills, including geology, mining, metallurgy, chemical engineering, manufacturing, finance, law, economics, data and analysis, ecology, environmental sciences, sustainable development and social sciences.

The UK has a long history of expertise in geology, mining engineering and metallurgy. We have skills in chemical engineering, as well as other science and engineering subjects, that are vital to critical mineral supply chains.

However, the skills base for critical minerals – particularly in mining and mineral processing – may be at risk. Provision of higher education in mining has been falling since the decline of the UK coal mining sector[footnote 12]. Of all mining and mineral processing engineers registered with the Engineering Council, 80 percent are over the age of 50 and nearly 40 percent are over the age of 66[footnote 13]. The number of university students studying geology in the UK nearly halved between 2014 and 2019[footnote 14]. This challenge is not unique to the UK. It creates a risk of a skills shortage at a time when we have the greatest need for them in recent decades.

We are home to world-leading educational establishments and want to promote the skills we need along the whole critical mineral value chain. These skills can support domestic critical mineral industries and as well as UK companies operating around the world.

We will train the next generation of miners, geologists, engineers and beyond.

- Work with Camborne School of Mines to boost its position as a world-leading mining school and launch a degree apprenticeship in mining engineering in 2023.

- Work with UK industry and careers services across the UK to deliver schools outreach on the importance of critical minerals and modernise perceptions of mining.

- Review the UK’s skills, education and training along the critical minerals value chain and define a critical minerals skills blueprint, recognising the full breadth of skills we need.

Europe’s leading education in mining

Camborne School of Mines at the University of Exeter is Europe’s leading institution of higher education in mineral and mining engineering[footnote 15]. It was founded in 1888 and is now located at the University of Exeter’s Penryn Campus, near Falmouth. It continues to deliver a multidisciplinary range of mining engineering training, qualifications and research programmes with close links to industry.

Employers from the mining sector have worked with the Camborne School of Mines to develop a new mining engineering degree apprenticeship programme, which has been approved by the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education and is planned to start in 2023. This apprenticeship will contribute to the skills needed for critical minerals mining in the UK.

Other UK universities also offer qualifications related to mining finance, law, data and management.

The skills we need do not stop at mining. The UK has a world-leading higher education offering, which will contribute to the broad range of skills and expertise the UK needs right along the critical minerals value chain. This will be delivered through our universities – for example, the University of Birmingham, which has a 40-year history in magnet manufacturing – as well as and other education and research institutions – like the Natural History Museum’s Earth Sciences Department, which has expertise in responsible use of natural resources.

The UK also has clusters of expertise in critical mineral activities, which are developing across the country (Figure 2). Expertise ranges from rare earth magnets manufacturing to lithium mining, from mineral exploration to trading and finance.

We will support the development of industrial clusters.

- Support the further development of industrial clusters for mining and refining of critical minerals, for example lithium extraction in Cornwall and mineral refining in North East England.

Research and development

We will promote innovation and re-establish the UK as a centre of critical mineral and mining expertise.

- Work with relevant research councils and public bodies to develop a critical minerals R&D blueprint to ensure we inform public R&D funding on the areas of highest priority in a coordinated way.

Research and development case studies

Innovate UK – This is the UK’s national innovation agency. It supports business-led innovation in all sectors, technologies and UK regions. Through various funding streams it helps businesses grow through the development and commercialisation of new products, processes, and services, supported by an outstanding innovation ecosystem.

Driving the Electric Revolution (DER) – DER is a UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund providing £80 million of investment to grow the UK’s electric vehicle supply chain and support its industrialisation. Investments include collaborative R&D, support for DER Industrialisation Centres and content and courses to grow the UK’s skilled workforce. It has already deployed over £8 million to projects related to critical minerals, such as the Recovery of Gallium from Ionic Liquids (ReGaiL) project on recovering gallium from end-of-life products, and the Rare earth Extraction from Audio Products (REAP) and Secure Critical Rare Earth Magnets (SCREAM) projects on recycling of rare earth magnets.

The Automotive Transformation Fund (ATF) – This also provides grant funding for late-stage development. Various critical mineral companies have received funding for scoping or feasibility studies, including Cornish Lithium, Weardale Lithium, Less Common Metals and Green Lithium.

Circular economy

We already have large quantities of critical minerals in the products we use today. As critical minerals become increasingly difficult to find and extract from the ground, it will be important to make best use of those already in circulation, through a circular economy.

Creating a more circular economy for critical minerals not only reduces waste, but also alleviates pressure on primary supply (i.e. from mining). An efficient circular economy of critical minerals would require increased recovery, reuse and recycling at the end of a product’s life, as well as better design and new business models for durability, resource efficiency and reuse. It would also require smarter use of critical minerals in the first place, through resource efficiency and substitution.

As products become more complex – a mobile phone can contain two-thirds of the elements from the Periodic Table[footnote 16] – they become increasingly difficult to recycle. The UK already has leading R&D on recovery and recycling of critical minerals and should look to enable commercial-scale capabilities to develop. Rather than exporting critical-mineral-containing technological waste, there is an opportunity to retain more critical minerals in the UK from end-of-life components.

Some high potential waste streams, such as electric vehicle motors, electric vehicle batteries, hydrogen fuel cells and wind turbine magnets, are still relatively low volume but will accelerate in the coming decades. There are synergies between the technology to reprocess critical minerals from waste and processing of primary minerals. There is some potential for capabilities that in the first instance could be used to process a higher volume of imported primary material, and as secondary materials become available, could switch to processing a greater proportion of secondary scrap[footnote 17].

The UK is already developing capabilities in recovery and recycling, particularly in rare earth magnets – like those used in electric vehicles and wind turbines.

Ongoing work on reuse, recovery and recycling of critical minerals

Increasing recovery and recycling of critical minerals can play a significant role in alleviating pressure on primary supply from growing demands. The UK has a range of novel recycling technologies and capabilities, as illustrated in the following examples:

UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) National Interdisciplinary Circular Economy Research (NICER) Programme is a £30 million programme to support a circular economy hub and five centres of excellence on circular metals, technology metals, chemicals, construction and textiles.

As part of this, Met4Tech is the Circular Economy Centre for Technology Metals, bringing together academic and industrial partners to identify system-level interventions to enable circularity in the production, use and reuse of technology metals. The Centre works with partners to join up along the value chain to deliver improved resource use and waste minimisation and develop a new technology metals circular economy roadmap.

The University of Birmingham has recently launched a pilot line to demonstrate novel engineering to recycle high-performance rare earth magnets.

Hypromag, a spin-out of this work, has developed an effective way of extracting rare earth magnets for recycling from end-of-life waste streams, such as hard disk drives, using patented Hydrogen Processing of Magnet Scrap technology, and is working to achieve this at an industrial scale.

GAP Group and Descycle are looking to use innovative chemistry to establish electrical waste recycling in the Northeast of England.

Battery maker Britishvolt and mining major Glencore are looking to build a battery recycling ecosystem in the UK, currently centred in Northfleet in Kent.

Johnson Matthey is the world’s largest recycler of platinum group metals, including at facilities in the UK.

We will promote innovation for a more efficient circular economy for critical minerals in the UK

- As part of the R&D blueprint, focus public R&D funding on recycling, reuse, resource efficiency and substitution of critical minerals.

We will signpost financial support to accelerate the development of a UK critical mineral circular economy

- Explore how government funding mechanisms can support companies developing domestic capabilities in the circular economy of critical minerals where the market is not working or where we make a strategic choice to accelerate progress.

We will look at regulatory ways to promote recycling and recovery

- Explore regulatory interventions to promote re-use, recycling and recovery of critical minerals, via the planned Defra consultation on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) regulations later in 2022 and future consultation on end-of-life batteries, including the Extended Producer Responsibility framework.

Collaborate with international partners

Diversification

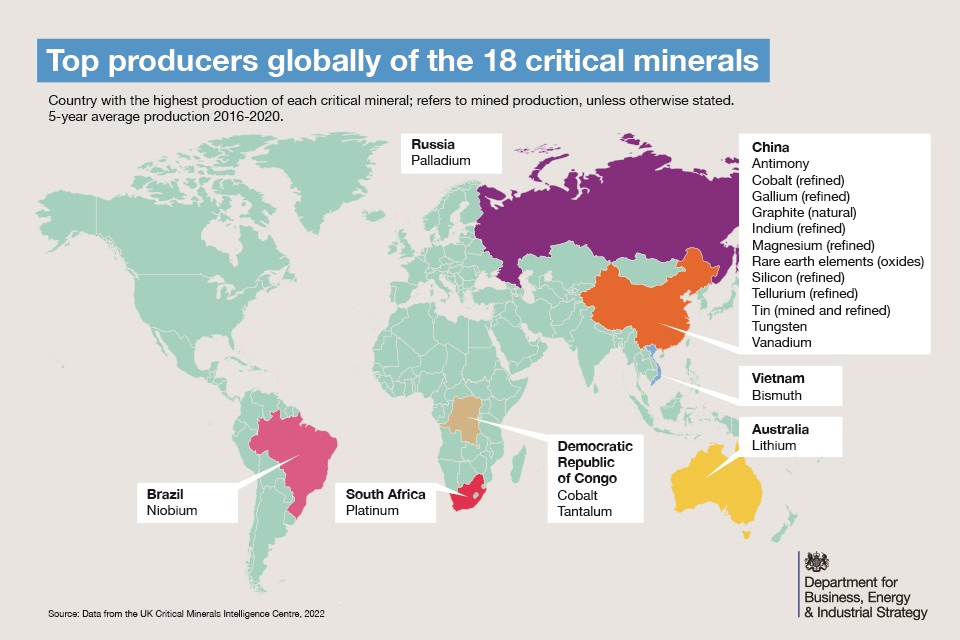

Critical mineral supply chains are highly concentrated. For each of the 18 critical minerals, the top three producer countries control between 73 and 98 percent of total global production. China is the biggest producer of 12 out of the 18 minerals[footnote 18]. Australia, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Russia, South Africa and Vietnam are the biggest producers of the remaining six (Figure 3). We believe that the more diverse our supply chains the more resilient they are.

Figure 3: Top global producers (5-year average 2016-2020) by mineral. Mined production unless otherwise stated[footnote 19].

Being highly dependent on any single country for specific goods creates vulnerabilities. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated how these risks can manifest themselves for a range of commodities. Concentrated control of resources creates a risk of economic statecraft whereby control is used as leverage on other issues[footnote 20]. The COVID-19 pandemic and other logistical disruptions also highlight the vulnerabilities in global supply chains. We support efforts to diversify supply chains as demand grows.

We will support efforts to diversify international critical mineral supply chains

- Build the case for a market-led, transparent and diversified supply chain with like-minded partners through the UK’s extensive multilateral engagement.

- Work with development banks to direct Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) towards helping like-minded, resource-rich countries develop critical mineral resources in a market-led way that aligns with sustainability, transparency, human rights and environmental goals, and supports our development priorities.

We will find out more about deep-seabed minerals and assess the challenges and opportunities of extracting them

- Continue to contribute to discussions on deep-seabed mining at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), pressing for the highest environmental standards in relation to existing exploration activity, and possible future commercial exploitation should that be approved by the ISA in the future.

- Proactively build our research base on deep-seabed minerals and the potential impact on deep-sea ecosystems should any deep-seabed mining be approved in future. Through the work of UK Seabed Resources, under the existing licences issued, we will deepen our understanding of the opportunities, challenges and potential impacts of deep-seabed mining to be able to contribute to the broader international discussions in this regard, allowing us to take any future decisions informed by the widest possible evidence base.

Critical minerals on the sea floor

Deep-seabed mining is the exploitation of resources from the deep-seafloor, from which minerals such as manganese, rare earth elements (REEs), nickel, cobalt and copper can be extracted. The majority of deep-seabed resources are located in areas beyond national jurisdiction, where mineral-related activities are regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), as mandated by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Some seabed resources are within national jurisdiction, where they are subject to domestic regulation, however, UNCLOS requires that such regulation shall be no less effective than that of the ISA.

Deep-seabed mining has gained interest owing to the rising demand for critical minerals. The opportunities and impacts are relatively unknown, and there are significant concerns about disrupting marine biodiversity and ecosystem. A recent cross-government commissioned independent expert review (to be published in due course) highlights that deep-sea ecosystems are considered to be particularly sensitive to disturbance, and recovery has not been shown to occur over decadal scales in test areas, with bigger commercial-scale impacts expected to last centuries.

The ISA exploitation regulations governing deep-seabed mining are yet to be finalised. In June 2021, the Republic of Nauru indicated an intention to sponsor an application for an exploitation licence within two years, effectively tasking the ISA to complete within two years the regulations necessary to approve deep-seabed exploitation applications.

The UK has agreed not to support the issuing of any exploitation licences for deep-sea mining projects unless or until there is sufficient evidence about the potential impact on deep-sea ecosystems.

The UK sponsors two deep-seabed mining exploration licences for UK Seabed Resources (UKSR) to explore a total of 133,000 square kilometres of the Pacific seabed. This project is working closely with UK government departments and research institutions on environmental, regulatory and industrial considerations of deep-seabed mining.

UK companies operating overseas

In the process of diversification of supply chains, we want the UK to contribute its expertise in responsible mining and enable UK businesses to play a role in the development of global supply. Whilst the participation of UK companies in the supply chains does not necessarily guarantee supply to the UK, it acts to positively influence security of supply through financial and commercial relationships, as well as shared values between producers and downstream manufacturers.

The National Security and Investment Act 2021 gives government powers to identify and, if necessary, intervene in acquisitions of control over entities and assets in or linked to the UK economy, including those in critical mineral value chains, which might cause national security concerns.

We will support UK companies to participate in building responsible, diversified supply chains overseas

- Focus DIT’s Clean Growth trade campaign activity on growing UK export of clean mining of critical minerals in strategic regions.

- Continue to make UK Export Finance products available to the critical minerals sector, including where this can support security of supply, as well as help export UK mining and mineral expertise, goods and services.

International partnership

The issues affecting critical mineral markets are global issues; no individual country can solve them alone. The UK will use its extensive engagement in international forums to promote the responsible development of supply chains and the circular economy and the improvement of existing ESG standards to make sure responsible UK businesses are not left at a competitive disadvantage. We will build relationships with influential countries and strategic producer countries that share our goals and engage constructively with others, while protecting our national security and values.

The UK is already engaged in many international initiatives, including:

-

The Minerals Security Partnership: The UK is part of a group of 10 countries and the European Commission aiming to spur investment into critical mineral supply chains to incentivise diversification in the market, while ensuring that critical minerals are produced, processed, and recycled in a manner that supports the ability of countries to realise the full economic development benefit of their reserves.

- The International Energy Agency (IEA): The UK is working with the IEA to explore ways to improve security of supply of energy-specific critical minerals.

- The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): The UK is co-facilitator for IRENA’s newly established Collaborative Framework, where its 166 member countries share expertise and discuss issues affecting critical minerals and their supply chains.

- G7: G7 Leaders have agreed to enhance collaboration, including with industry, to understand vulnerabilities and to strengthen security of critical supplies. This focus will be on promoting market circularity, supporting diversification, sharing insights and best practice on these markets, and building responsible, sustainable, and transparent critical minerals supply chains.

- United Nations (UN): The UK has engaged in the development and implementation of the United Nations Framework Classification for Resources and United Nations Resource Management System in respect of critical minerals, via the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe[footnote 21].

- UK-Australia: In 2020, the UK and Australia formed a Critical Minerals Joint Working Group, aiming to deepen collaboration on critical minerals. Government continues to deepen cooperation between UK and Australian businesses to support mutually beneficial, demand-led growth that improves the security of responsibly sourced critical minerals.

- UK-Canada: In March 2022, Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada agreed to strengthen our strategic cooperation on economic resilience, including critical minerals and supply chains. This will further develop existing collaboration on areas of common interest, including to promote high ESG performance and drive R&D and innovation in critical minerals.

- UK-US: The UK is working closely with the US in multiple forums and is a founding member of the US-designed Minerals Security Partnership, along with collaborating with the US in the IEA, G7, and other forums.

- UK-South Korea: In February 2022, the UK and South Korea signed an agreement to strengthen supply chain resilience, which will include discussions on critical minerals.

The Minerals Security Partnership

In June 2022 at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) conference in Toronto, the UK and other like-minded nations entered into the new Minerals Security Partnership. The Partnership was proposed by the US State Department and founding members include Australia, Canada, the European Commission, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the US and the UK. The partnership aims to spur investment into critical mineral supply chains to incentivise diversification in the market, and is focused on four pillars:

Information Sharing and Cooperation: building on existing partnerships to establish an information exchange to address non-sensitive information;

Investment Network: forming a network of governments, development finance institutions, and multilateral investment banks to review opportunities and coordinate support for priority private sector-led projects that advance secure and sustainable critical mineral supply chains;

Elevation of ESG Standards: committing to high environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards, including in those projects it invests in;

Recycling and Reuse, helping countries to: advance minerals recycling, reuse, and recovery; improve enabling environments for waste management and collection for recycling of batteries and other products made with critical minerals; and leverage relevant R&D cooperation.

We will engage with key countries bilaterally on critical minerals, to promote joint working towards solutions to global issues in critical mineral value chains.

- Engage our closest partners to co-ordinate on tackling global supply issues, sharing market intelligence and boosting collective resilience.

- Engage emerging producer countries (including those in the network of Commonwealth countries) to support development priorities, engage them in regulatory diplomacy, help develop resources in a way that works for communities and our natural environment, and create opportunities for responsible UK companies and investors in those regions.

- Engage investment partners to co-ordinate investment and create opportunities for UK businesses.

- We will explore ways to lower barriers to trade of critical minerals, including as part of Free Trade Agreements.

Case study: UK-Canada engagement

The government is further deepening its close relationships with Canada on critical minerals. As the Joint Statement between our Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the Prime Minister of Canada, the Rt Hon Justin Trudeau MP, set out in March this year:

“We will strengthen our strategic cooperation on economic resilience, continuing our close engagement on critical minerals and investment security, and establishing an overarching UK-Canada initiative on critical supply chains to identify concrete shared action and coordinate approaches to risks and vulnerabilities, drawing on each country’s strengths and experience to deliver solutions.”

Officials are sharing emerging views on policy, agreeing shared interests and supporting UK and Canadian industries to collaborate. In May 2022, the UK led a Global Expert Mission to Canada to share UK expertise on critical minerals. Ministers from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Department for International Trade have visited Canada and are working with national, provincial and territorial governments in Canada to further develop relationships and unlock synergies between Canada and the UK.

We will continue to build plurilateral and multilateral partnerships to tackle global issues.

- Begin discussions with multilateral development banks on lending requirements for critical mineral mining projects, with the goal of supporting the responsible practices that boost the security of supply and ensure sound governance and anti-corruption standards.

- Use the IEA and IRENA to explore ways, in collaboration with others, to improve security of supply of minerals that are critical for the energy transition.

- Use the Minerals Security Partnership to catalyse investments among likeminded countries to make critical mineral supply chains more diverse, responsible and resilient.

- Engage with the G7 to intensify work towards building responsible, sustainable, and transparent critical minerals supply chains.

China

China dominates several key critical mineral supply chains. Of the 18 critical minerals, China is the largest producer for 12 of those minerals, either as a raw material or refined product. We need to continue to engage with China to achieve our objectives, including to improve ESG performance in critical mineral supply chains, while continuing to strive for diversified and resilient supply chains.

Enhance international markets

Resilience through ESG performance

Critical mineral supply chains are fraught with ESG issues and risks. These issues can breed instability and community or political resistance to mining projects, adding vulnerability to supply chains. They also cause economic, social and environmental harms and could impede investment and create reputational risks for companies.

Irresponsible or illegal mining – not just for critical minerals, but also major metals like gold, iron ore and copper – is linked to pollution, ecosystem damage, carbon emissions and water table depletion. For example, mining is a leading cause of deforestation – 44 percent of large-scale mines are based in forests[footnote 22] – which increases the sector’s global contribution to climate change. It has been shown to impact biodiversity and degrade ecosystems[footnote 23].

Irresponsible or illegal mining can also cause safety risks for workers and communities, competition for water, forced or child labour, resettlement, corruption and human rights abuses of workers, communities or indigenous people.

ESG issues and risks are not limited to the mining sector, but also affect refining, manufacturing and recycling of critical minerals. The issues are also not limited to critical minerals – they are common across many mined commodities such as gold, iron ore and copper – which necessitates broader engagement across the mining sector as a whole.

The government is continuing to build its evidence base on environmental and social challenges. Improving ESG performance can increase resilience, and the UK can play a central role in that effort.

Certain UK companies have demonstrated novel approaches to ESG challenges. In the wake of the 2019 disaster at Brumadinho, Brazil, where a tailings storage facility failed, killing 270 people in 2019, the Church of England Pensions Board co-founded the Investor Mining and Tailings Safety Initiative (IMTSI) to drive safety in the mining sector[footnote 24]. UK mining major, Anglo American, is industry leading on policies and practices on economic, environmental, social and governance issues according to the Responsible Mining Index[footnote 25]. Earlier this year, Anglo American also developed of the world’s largest hydrogen-powered mine haul truck, demonstrating potential for reducing the environmental impact of the mining sector. UK companies are also leading the way in remote monitoring of ESG performance, through sensors and satellites for example.

We want to level the playing field for responsible UK businesses operating overseas, who bear the extra costs of doing things the right way while others do not.

Through our stakeholder engagement work, we know that major manufacturers are increasingly looking to source materials that are traceable and can prove high standards. We also know that UK financial institutions are demanding strong ESG credentials for investment. With the right support, this can help drive change through the supply chain.

The UK will use its wide-ranging membership of international forums to explore how we can work with partners to improve existing global ESG standards that support a more transparent, responsible and sustainable critical minerals industry.

Case study: Corruption risks in the critical minerals supply chain

Corruption is a barrier to the achievement of UK and global climate change goals, as it can undermine the efforts of resource-rich countries to reduce poverty, diversify their economies, achieve democratic governance and address the climate crisis. The forms of corruption range from individual bribery through to systemic corruption in kleptocracies.

The extractive industries are one of the highest risk sectors for corruption: one in five cases of transnational bribery happen in this industry[footnote 26]. The oncoming boom in critical mineral mining risks further exacerbating these risks. In the rush to develop supply, companies may prove willing to take more risk, and regulators will need to keep pace. Many of the locations of critical mineral reserves are in jurisdictions that have high corruption risks[footnote 27]. A more secure supply of critical minerals requires progress towards stronger policies and practices in major producer countries. Directly addressing corruption and working to strengthen governance forms part of this strategy’s measures to strengthen ESG performance, particularly through the UK’s international engagement. This activity will link to government’s broader efforts to address corruption in climate, environment and energy including through a refreshed UK Anti-Corruption strategy, due in 2023.

Last year, HM Treasury published Greening Finance: A Roadmap to Sustainable Investing[footnote 28], which focuses on ensuring that the information exists to enable financial decisions to factor in sustainability. It commits to implement a Green Taxonomy to provide a shared understanding of which economic activities count as green. The government will consult on technical screening criteria in the coming months, and we will explore how the importance of critical minerals to renewable energy technologies, in particular, could be reflected in the UK Green Taxonomy.

We will play a leading role in global efforts to drive up ESG performance to improve resilience of supply chains and level the playing field for responsible UK business overseas.

- Continue to play a leading role in initiatives to streamline and implement proportionate global ESG standards in the critical minerals supply chain, for example through the European Partnership for Responsible Minerals (EPRM), Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), G7, United Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), Minerals Security Partnership and others.

- We will publish a review of current global activities, research and policy leading to the identification of the key issues related to critical mineral resource management and the sustainability of supply. This will include an evaluation of the role of the United Nations Framework Classification (UNFC) in classifying and harmonising critical mineral resource data, and discuss potential application of the United Nations Resource Management System (UNRMS).

- In line with the UK’s regulatory principles – as set out in the government’s paper on the benefits of Brexit[footnote 29] – we will engage in regulatory diplomacy across the world, focused on the areas that most affect our long-term strategic advantage, economic security and competitiveness, core values and security in support of UK business and citizens now and in the future.

- Increase efforts to address corruption through the extensive international engagement activity outlined in this strategy. We will work with allies and partners to promote beneficial ownership transparency, open contracting and strengthen governance frameworks of developing countries with mineral resources.

We will role model standards for sustainable development of resources in the UK.

- Ensure UK domestic mining complies with permitting and planning regulations, and encourage the proportionate use of globally recognised frameworks and guidelines for responsible mining and investment where applicable – for example EITI standards, - Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), ICMM principles, the Equator Principles, and UN Resource Management System (UNRMS) – that protect the interests of communities and our natural environment.

- Explore how ambitions for new Sustainability Disclosure Requirements[footnote 30] can support ESG performance of critical minerals in the UK.

Well-functioning and transparent markets

Critical minerals are complex with many stages of processing and many variations of product. Data are not readily available to track production and flow of critical minerals along the value chain. Market intelligence on global supply chains is fragmented and not well publicised. Many critical mineral markets can be described as “incomplete markets” because there is no organised market on which to trade.

Markets are volatile and have a history being manipulated. In 2010, China reduced its export quota of rare earth elements, which had the effect of causing rare earth prices to spike sharply. The price of one rare earth commodity, cerium oxide, rose by over 400 percent between the end of July and beginning of September[footnote 31].

It is in the UK’s interests to support well-functioning markets, to help de-risk investments and development of new projects. The City of London is well-placed to lead this effort, as the global centre of metals trading, including hosting the London Metals Exchange and major mining finance organisations.

Government has a role as a convenor on data and traceability, leveraging the expertise of UK industry. HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Integrated Data Service Phase C, alongside a consortium of experts from industry and academia, are running a small-scale data pooling pilot collecting information across the supply chain, demonstrating data sharing environments can be safely created with appropriate safeguards, transparency and accountability.

It is also important for government to gather market intelligence on critical mineral markets to inform policy making and understand urgent or emerging risks.

We will find out where critical minerals are produced, how they are traded and where they are used – both now and in future.

- We have launched the CMIC to improve UK’s insight into supply and demand of critical minerals, market dynamics and emerging risks, which will inform evidence-based policymaking and be of value to UK industry.

- Deliver the ambition of the National Data Strategy by making better use of data and leveraging the UK’s existing strengths. We will do that by focusing on good foundations, making that data available, and free-flowing both domestically and internationally, to track and measure critical mineral flows.

The Critical Minerals Intelligence Centre (CMIC)

The complexity and opacity of critical mineral supply chains makes it very difficult to monitor their supply, demand and market dynamics. Market intelligence is fragmented and not well publicised. Better intelligence is needed to manage risks associated with critical mineral supply to sustain UK high-value manufacturing, and to enable delivery of net zero objectives.

BEIS established the CMIC, launched in July 2022, to provide data and analysis on sources of the supply, demand and market dynamics of critical minerals, as well as insights on factors affecting these markets such as ESG issues and geopolitical events. This will help demystify markets, support government policymaking decisions and help secure robust supplies of critical minerals.

The CMIC will be delivered by the British Geological Survey (BGS), one of the world’s foremost geological surveys with access to objective and authoritative geoscientific data, analysis and expertise. BGS will work with partners from across industry and academia, in the UK and overseas, to provide the required research and analysis.

For information: https://ukcmic.org/.

We will make global markets function more effectively and be more transparent.

- Convene a dialogue between UK mining, mining finance and metals trading communities in the City of London to progress the development of structured trading in critical mineral markets.

- Leverage our role in the WTO to ensure critical mineral markets are conducted according to WTO rules.

- Continue multilateral and cross-sector engagement on global technical International Organization for Standardisation (ISO) standards for critical minerals, to support better data and transparency throughout their value chains.

We will promote innovative techniques to help UK companies trace where minerals are from.

- Continue government-led supply chain traceability initiatives on critical minerals, such as those underway through HMRC and ONS.

A global capital of responsible finance for critical minerals

As a centre of mining finance and metals trading, the City of London is already influencing standards, positioning ESG as a key investment criterion. London is also home to the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), who set global standards for safe and responsible mining.

We will position the UK as a centre of responsible international mining.

- Engage industry, standards organisations and the financial sector to promote the City of London as the centre of responsible mining finance and facilitate responsible investment.

Delivering the strategy and measuring our success

Some of the measures described in this strategy will see immediate benefits, while others will reap benefits in the longer term, but need to be enacted now to mitigate future risks and safeguard our future industries.

This strategy is designed to set an ambition, recognising that – in many cases – more work needs to be done to scope, test and implement the actions described.

The actions cut across government departmental boundaries, so it will be important that departments work together effectively. BEIS will act as the policy lead on critical minerals and the Cabinet Office will co-ordinate cross-government engagement.

With the launch of this strategy, government departments are engaging to agree an action log to manage the delivery of it. Actions will be assigned, monitored, evaluated and adapted through established governance and accountability arrangements across government.

We will publish a delivery plan for the commitments in this strategy later in the year.

BEIS will continue to convene the Critical Minerals Expert Committee, adapting its scope (and membership, if needed) to advise on the delivery of the strategy, emerging risks to security of supply and opportunities for the UK government.

We will establish a dedicated Critical Minerals Unit to act as government’s single point of contact with the critical minerals sector, including business, academia and civil society. In the first instance, this will be focused on engaging stakeholders and bringing together existing expertise across government. Over the coming year, we will design and build the Unit for the long term to support the objectives of the strategy and the needs of the sector.

Glossary

Circular economy: Most of what we consume flows through a linear, ‘take, make, waste’ economy. According to the UKRI National Circular Economy Research Hub, a Circular Economy, by contrast, focuses on regeneration, restoration, and re-use at all stages of a resource’s life cycle. This allows products, materials, and components to remain in circulation at their highest value for the longest period, and the waste generated by a linear economy is designed out from the start. Importantly for critical minerals, it also alleviates pressure on supply of primary (mined) resources.

Critical minerals: Minerals of both high economic importance and high risk of supply disruption. For further information on how minerals are evaluated to be “critical”, see the UK criticality assessment of technology critical minerals and metals[footnote 32].

Deep-seabed mining: The exploitation of resources from the deep-seafloor, from which minerals such as manganese, rare earth elements, nickel, cobalt and copper can be extracted.

Gigafactory: A facility to manufacture batteries for electric vehicles at scale.