Key Findings

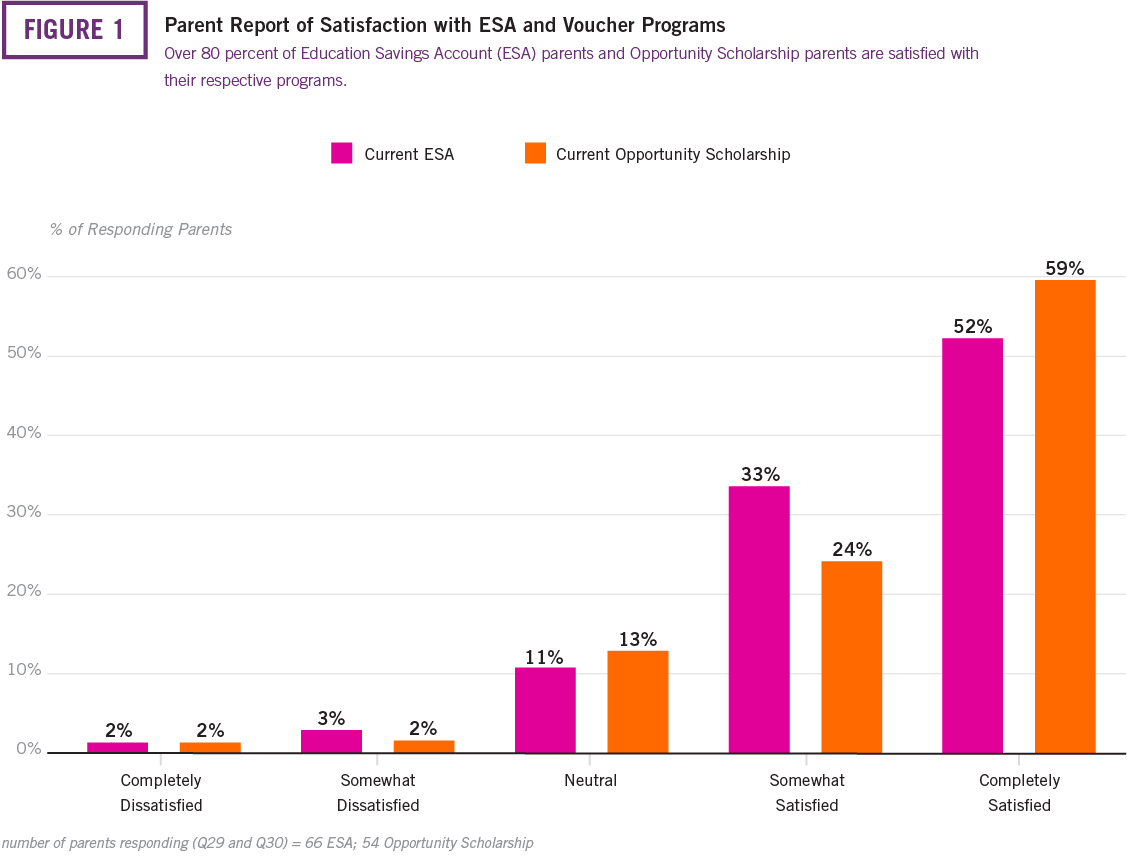

- Over 80 percent of Education Savings Account (ESA) parents and Opportunity Scholarship parents are satisfied with their respective school choice programs.

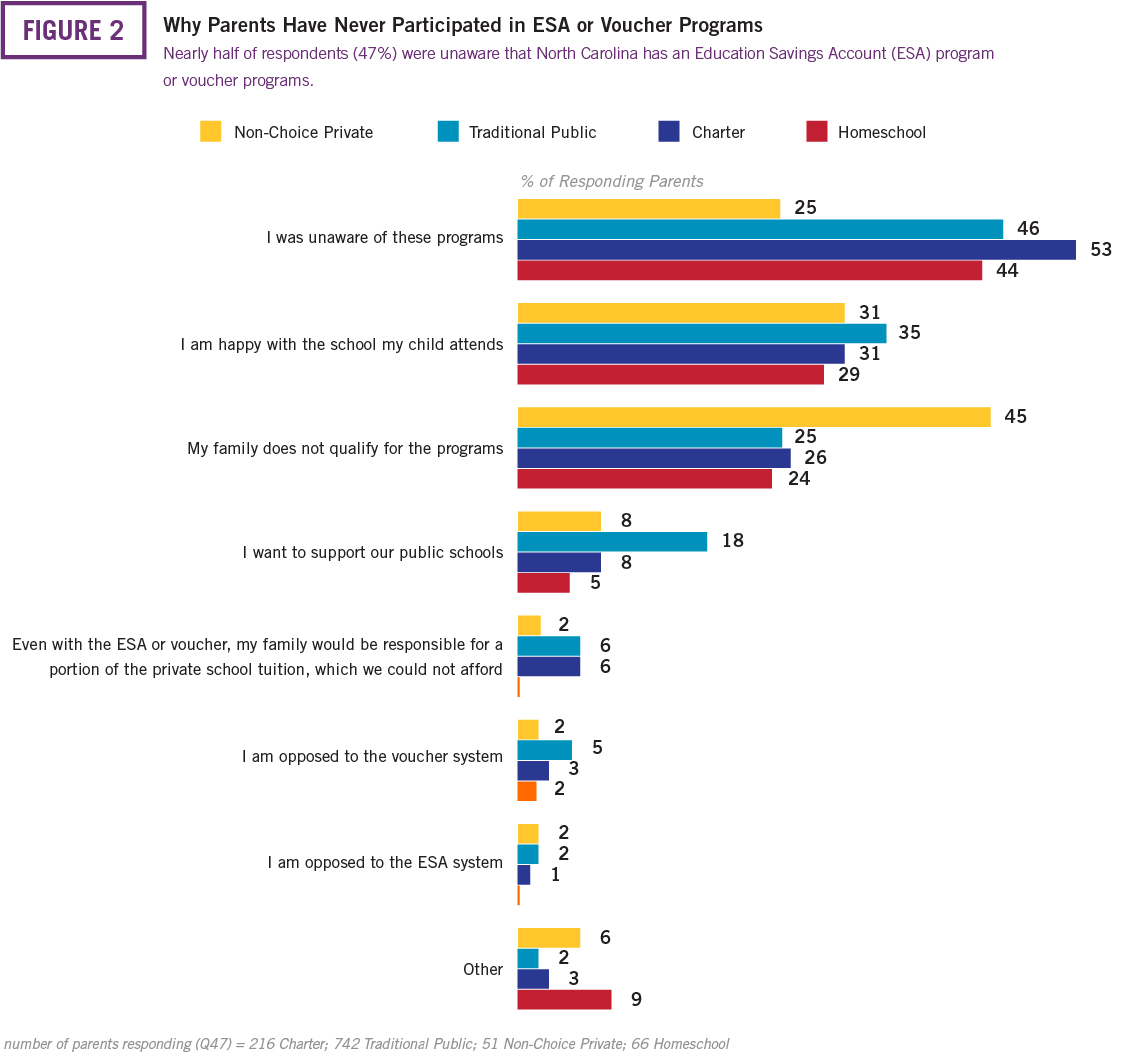

- Nearly half (47%) of private, charter, traditional public, and homeschool parents who have never had a child participate in an ESA or voucher program said they were unaware the programs existed.

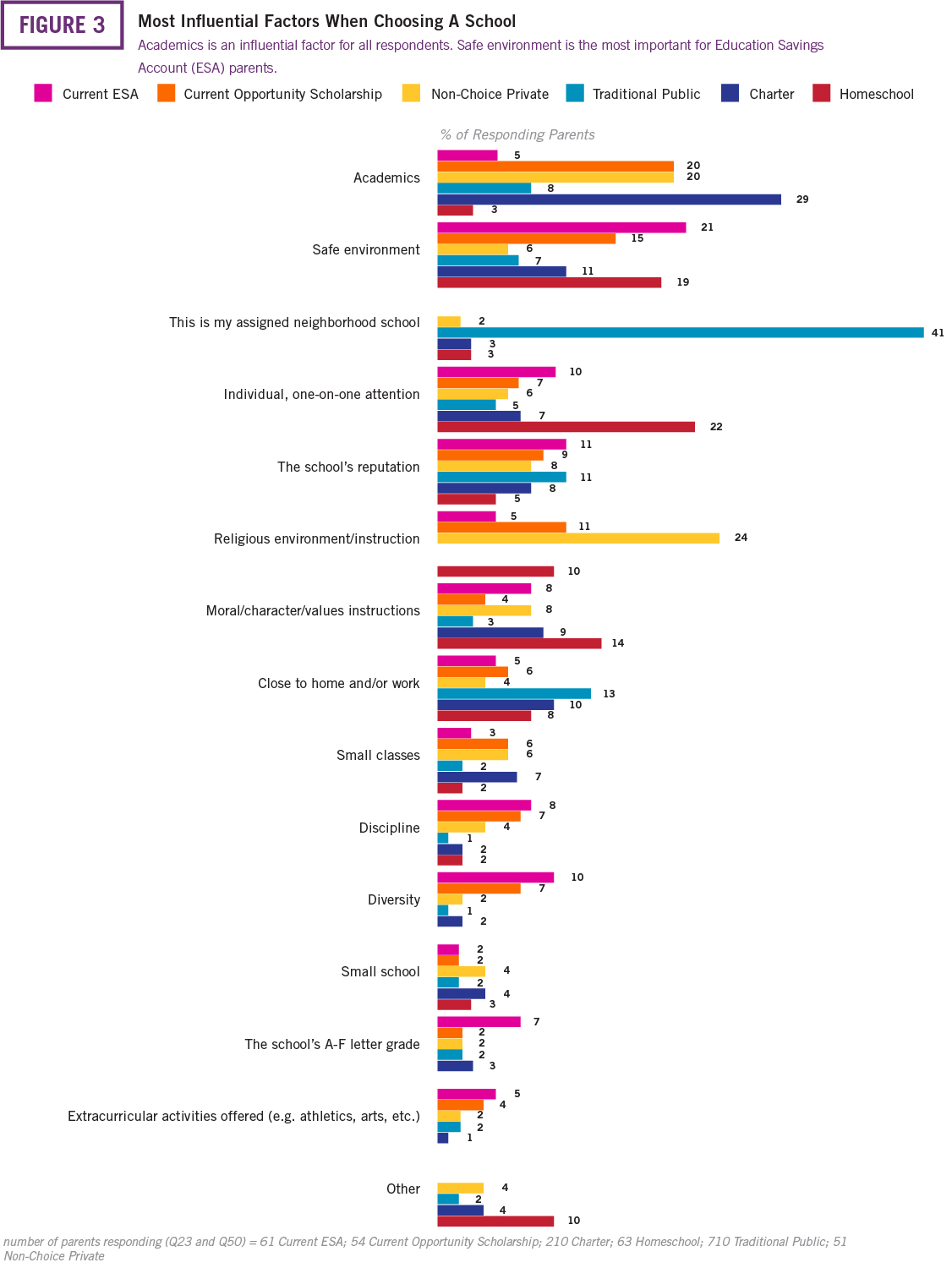

- Academics is an influential factor for all respondents when choosing a school. Safe environment is the most important reason for ESA parents.

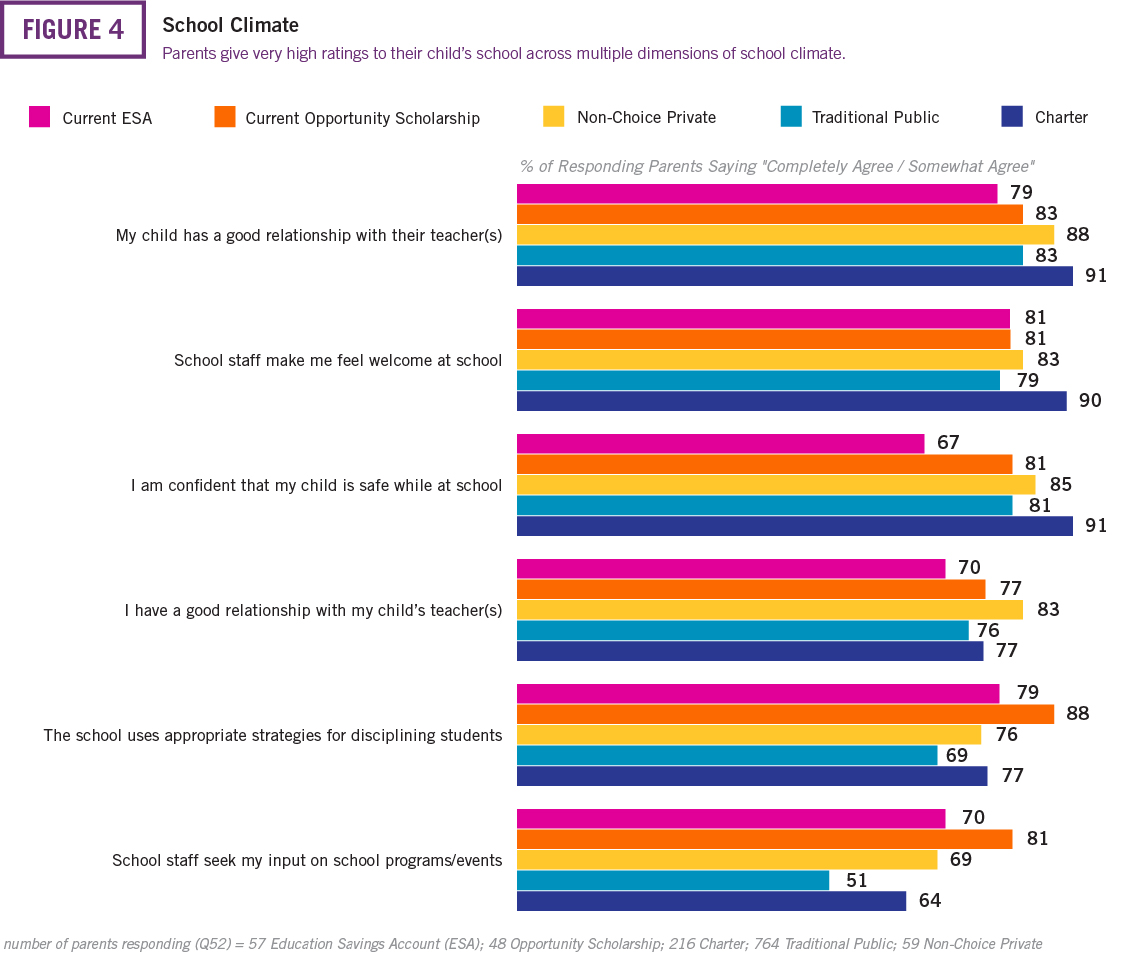

- Parents give very high ratings to their child’s school across multiple dimensions of school climate.

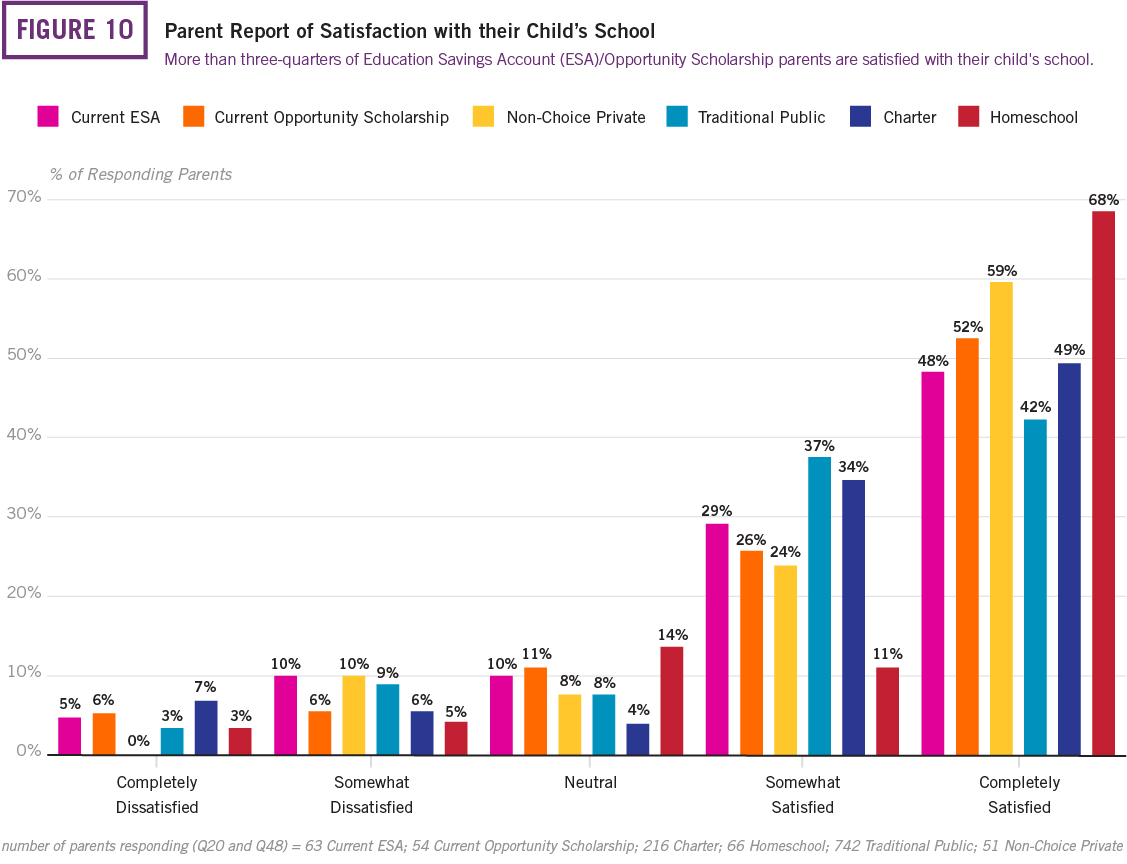

- Although their satisfaction levels are lower than parents with children in other schooling sectors, more than three-quarters of ESA and Opportunity Scholarship parents are satisfied with their child’s school.

- 73 percent of ESA parents and 74 percent of Opportunity Scholarship parents are more satisfied with their program school than their child’s pre-program school and only 6 percent of each group said they are less satisfied.

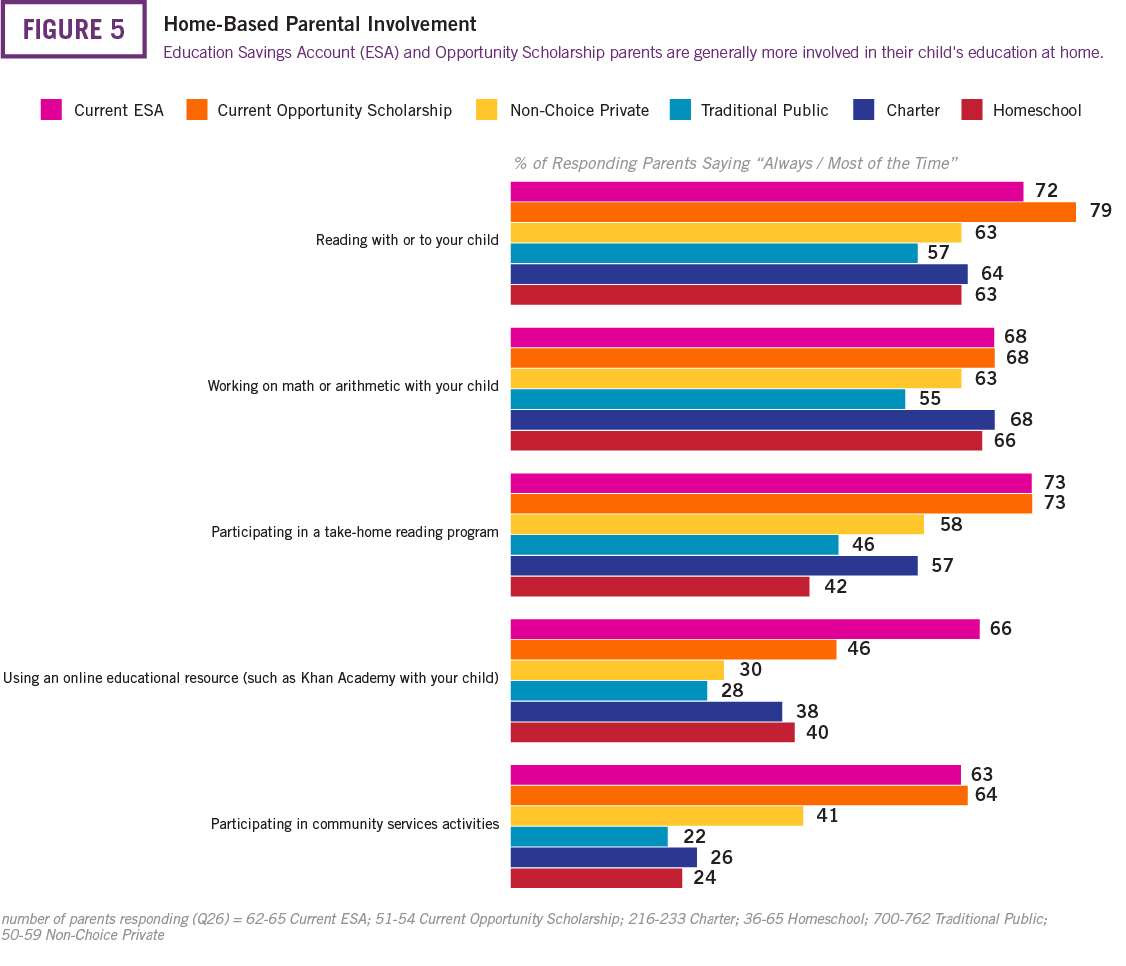

- ESA and Opportunity Scholarship parents are generally more involved in their child’s education at home, especially compared to traditional public school parents.

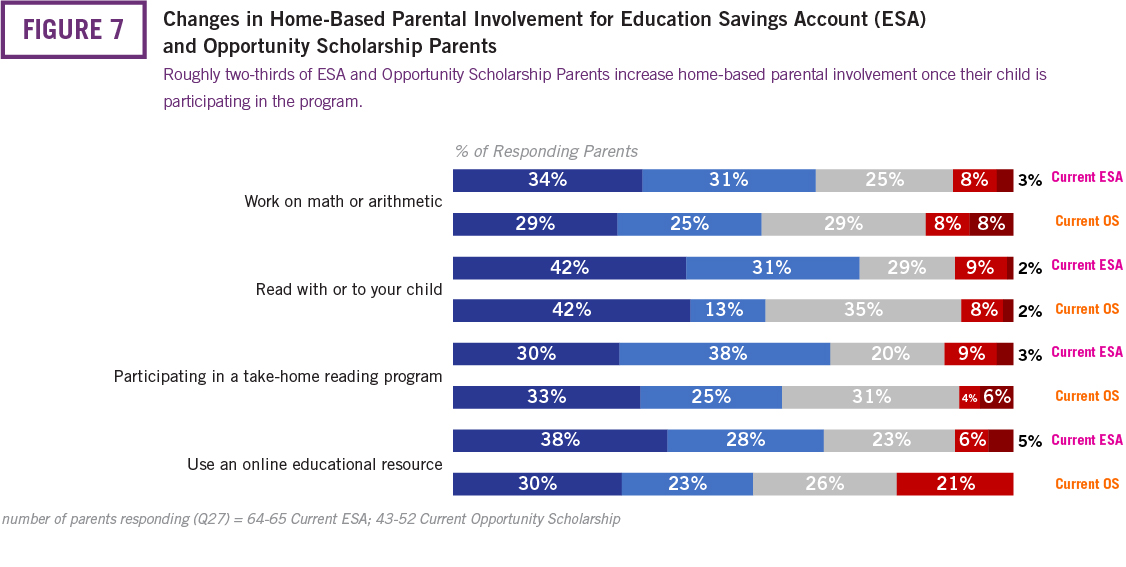

- Roughly two-thirds of ESA and Opportunity Scholarship Parents increase home-based parental involvement once their child is participating in the program.

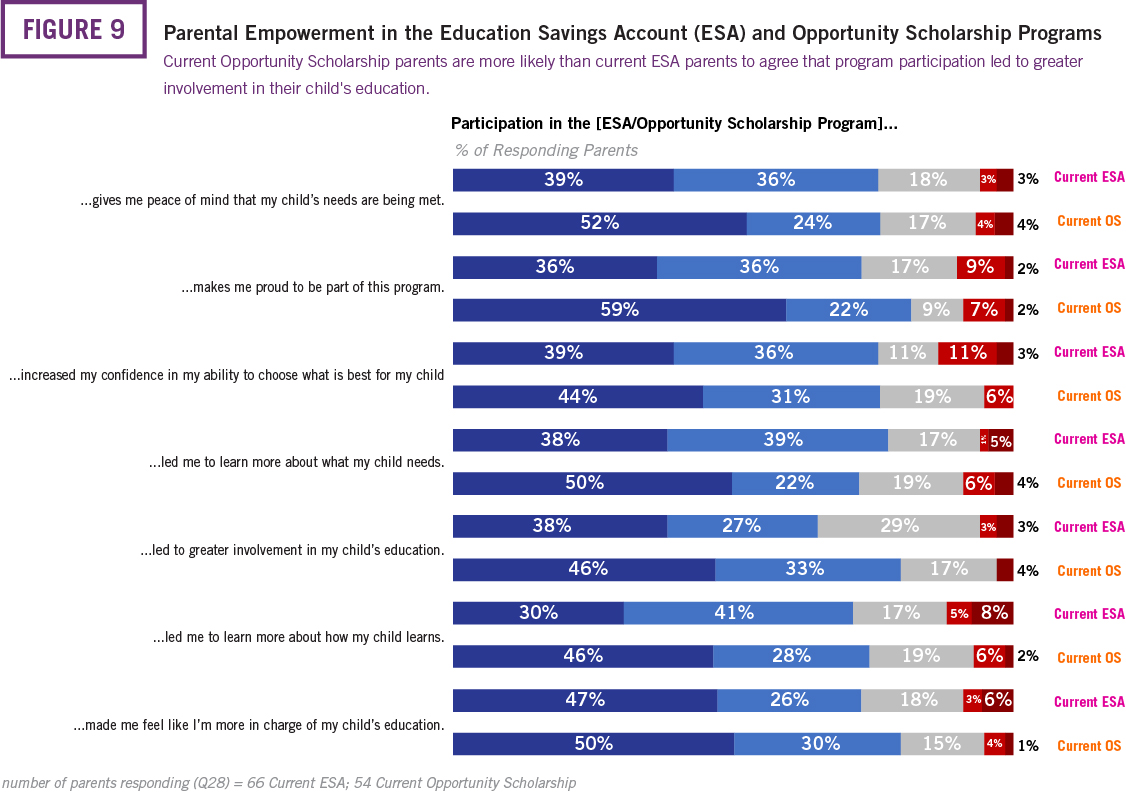

- Opportunity Scholarship parents are more likely than ESA parents to agree that program participation led to greater involvement in their child’s education.

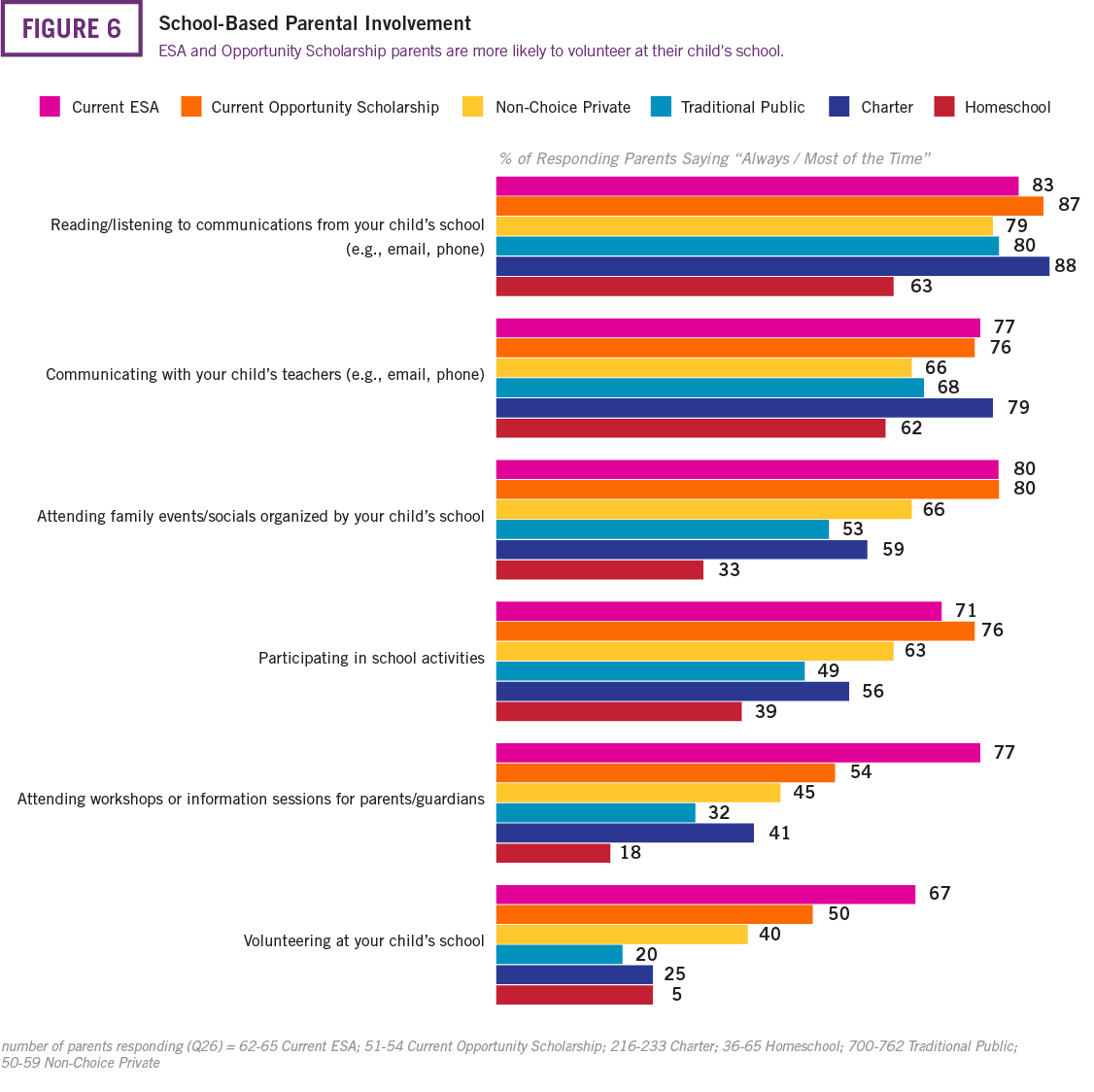

- ESA and Opportunity Scholarship parents are more likely to volunteer at their child’s school than other parents.

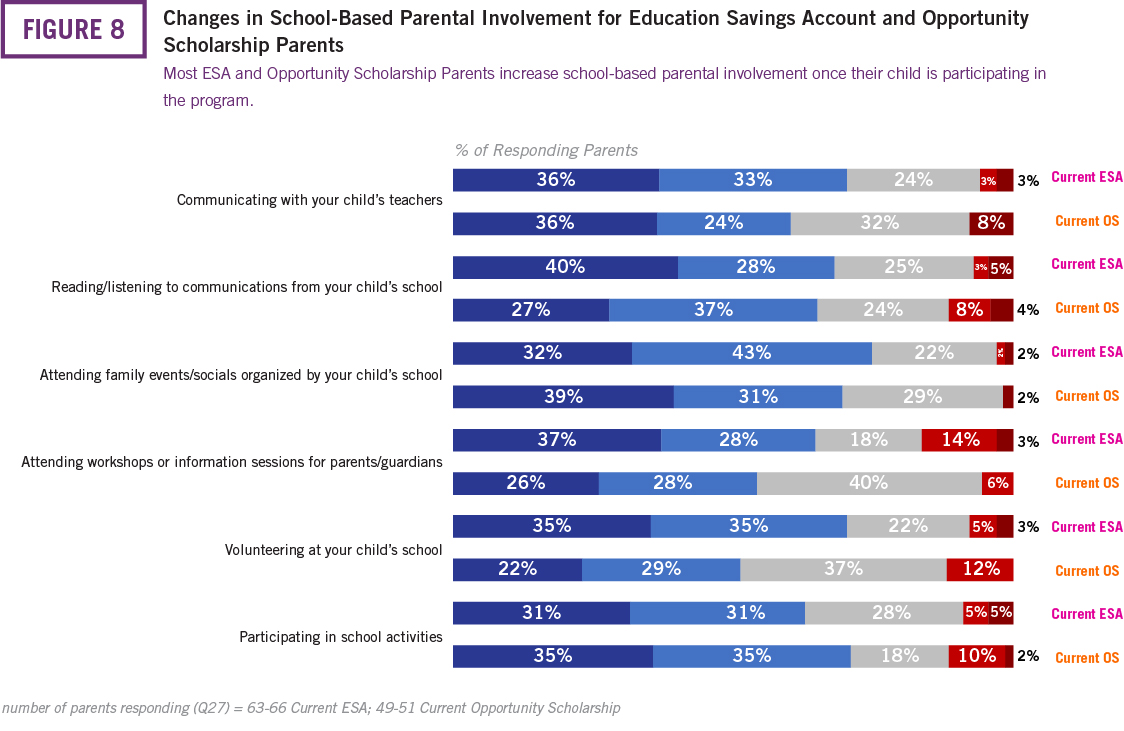

- Most ESA and Opportunity Scholarship Parents increase school-based parental involvement once their child is participating in the program.

Overview

North Carolina is home to a growing and evolving K–12 education landscape. The state experienced a 21 percent increase in its public elementary and secondary school enrollment since 2000, with that figure projected to grow by another 4 percent by 2028.1 The state has garnered attention for its emphasis on individualized education and implementation of federal funding plans, while also experiencing significant increases in its schools’ segregation levels.2 Those in the Research Triangle and elsewhere may have mixed feelings when learning North Carolina students significantly increased their achievement levels in math during the latest NAEP examinations, commonly referred to as The Nation’s Report Card, while seeing decreases in science scores.3

The state is also home to other growing K–12 education sectors. More than 100,000 students in North Carolina attend charter schools. North Carolina’s 184 charter schools are found in all corners of the state, with more than 20 additional charter schools expected to come on board in the near future.4 An even greater number of private schools (28) started in North Carolina during the 2019–20 school year.5 And even before the COVID-19 pandemic, which nudged a flurry of parents to apply for homeschooling status with the state in preparation for the Fall 2020 semester, roughly 150,000 students in North Carolina were homeschooled.6

North Carolina currently offers several school choice programs that help families access private schooling and other education options. The state’s Opportunity Scholarship Program, launched in 2014, provides low-income students with vouchers worth up to $4,200 per year to attend private schools.7 Another voucher program in North Carolina, the Special Education Scholarship Grants for Children with Disabilities, reflects its namesake in funding private school tuition and specialized services to students with special needs. Accounting for the increased costs of educating special needs students, the seven-year-old program offers $8,000 per school year to qualifying students.8 Finally, North Carolina offers an additional avenue of financial assistance to students with special needs in the form of its Personal Education Savings Account Program, which is a recently launched K–12 Education Savings Account (ESA) providing up to $9,000 per year to qualifying students to be used for a variety of educational and therapeutic uses both in and outside of the classroom.9 While its enrollment is currently a fraction of the state’s other two school choice programs, North Carolina’s program was designed to be complementary to the state’s vouchers and allows for voucher funds to be stacked atop of ESA funds for qualifying families.

While these programs are relatively young, researchers have been able to analyze them in a variety of ways. In an assessment of applicants to the Opportunity Scholarship, academics found those applying were among the lowest-income households in the state.10 A quasi-experimental study observed small math and language test score gains by first-year voucher students, with no significant effect on participants’ reading scores.11 Parents utilizing the Opportunity Scholarship were also found to be overwhelming satisfied with their children’s schools.12

In this brief, we continue the study of North Carolina’s school choice programs by surveying K–12 parents in the state. We focus on the ESA and Opportunity Scholarship programs, as well as how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed parents’ educational experiences in the state. In analyzing responses to our survey, we identified families using these programs to understand who uses them, why parents decide to use these programs, and how parents feel about them. We also provide responses from parents of students enrolled in private school but not participating in an ESA or voucher programs (non-choice private), traditional public schools, charter schools, and homeschool.

Results

This survey reports on the views and preferences of parents of K–12 students residing in North Carolina. It follows in the line of similar EdChoice surveys of parents who utilize or have been familiarized with private school choice programs. It differs from these prior projects, though, in also asking parents about their experiences and education adaptions stemming from COVID-19-related school closures and online instruction. The survey was administered in early summer 2020, right after schools in North Carolina had concluded their pandemic-altered spring semesters.

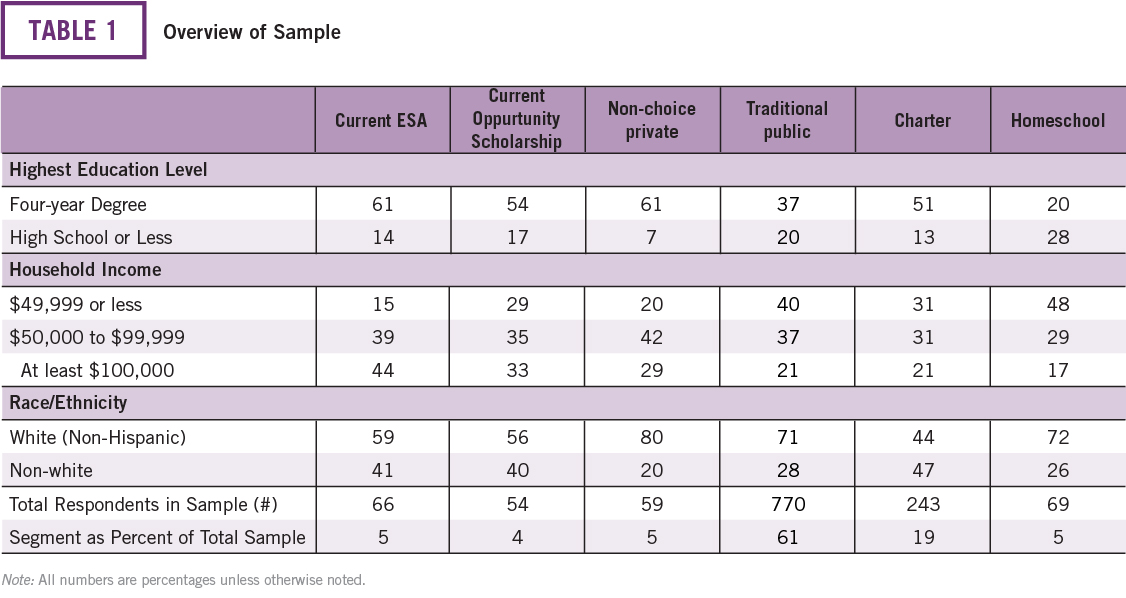

The survey represents parents from all schooling sectors in North Carolina, containing a total sample of 1,261 parents with at least one student in the K–12 grade range during the past two school years. While the sample is not representative of the exact proportion of students by schooling sector in North Carolina, it contains a large enough population of private school families to sub-divide parents by three characteristics: (1) current ESA users, (2) current Opportunity Scholarship users, and (3) non-choice private school parents. Along with parents of charter school, traditional public school, and homeschool students, these private school choice categories allow for a two-dimensional comparison of parental preferences while also gauging parents’ experiences with North Carolina’s special education ESA and low-income voucher programs.13

Education Savings Account (ESA) and Opportunity Scholarship Programs

In the sample, 66 respondents are parents of students in North Carolina’s Education Savings Account (ESA) Program, and 54 students are parents of students in North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarships programs.

Perceptions of the ESA and Opportunity Scholarship programs are generally positive among participating families in our sample. More than four out of five current ESA parents (85%) and current Opportunity Scholarship parents (83%) report being satisfied with their respective programs. By contrast, only 5 percent of ESA parents and 4 percent of Opportunity Scholarship parents express dissatisfaction with them.

If they were not participating in their respective programs, less than one-fourth of ESA (24%) and Opportunity Scholarship parents (24%) said they would still have their child enrolled in a private school. When parents who have never had a student participate in an ESA or voucher program in North Carolina were asked why not, nearly half (47%) were unaware of the existence of the programs.

Factors Underlying School Selection among Education Savings Account and Voucher Users

When choosing a school, parents report having a variety of educational goals and priorities in mind. This diversity of educational preferences has been well documented in numerous surveys of parents across the country.14 The inception of ESA and Opportunity Scholarship programs may have enabled parents to more easily select schools that they perceive to meet particular goals and priorities. On our survey, we explored this issue by asking parents what they believed to be the purpose of education. We further asked parents to identify school characteristics that were influential in selecting a school that their child currently attends.

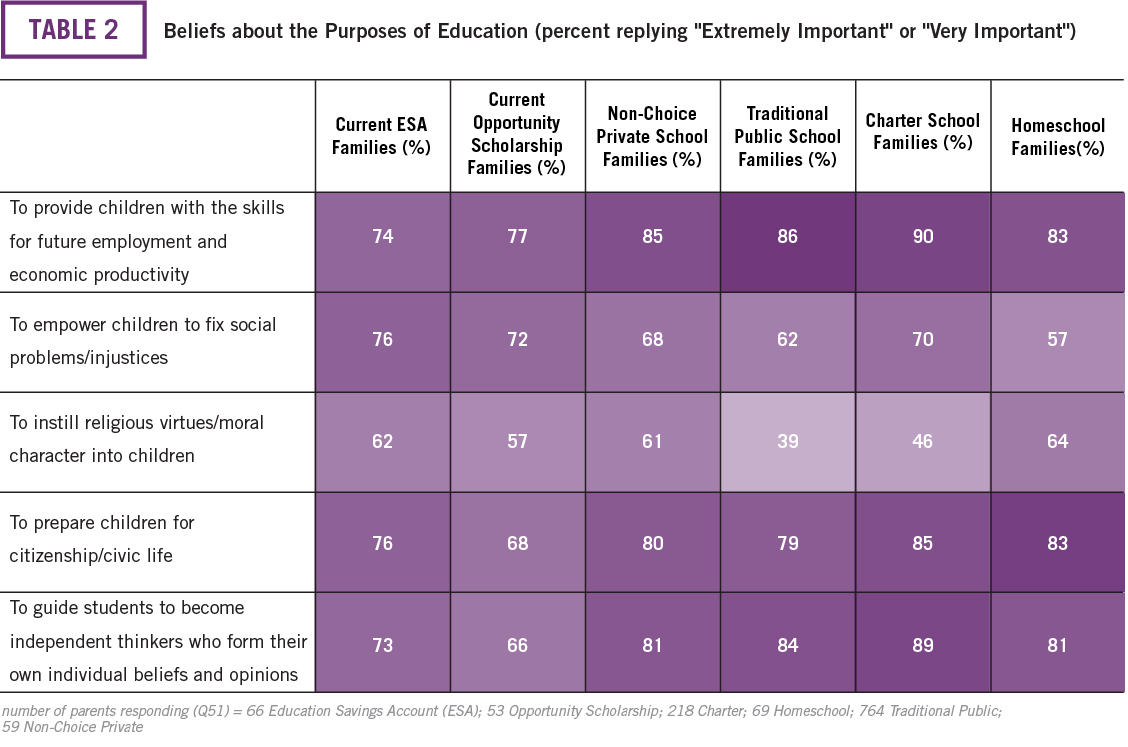

Table 2 presents parents’ beliefs about the purpose of education. Parents who participate in ESA and Opportunity Scholarship programs are distinguished by their conceptions of the purpose of education. At least 83 percent of parents with children in traditional public schools, charter schools, homeschool, or private schools (non-choice) believe that preparation for future employment and economic productivity is a “very” or “extremely important” purpose of education, but only 74 percent of current ESA and 77 percent of current Opportunity Scholarship parents share this view. Parents of children currently participating in ESA and voucher programs are slightly less likely than other parents to cite as “very or extremely important” purposes of education: (1) preparing students for civic life, and (2) helping students become independent thinkers who form their own beliefs or opinions. Parents of children currently participating in ESA and Opportunity Scholarship programs are slightly more likely than other parents to believe that empowering children to fix social problems/injustices is a “very or extremely important” purpose of education.

Respondent groups vary widely when it comes to which factor is the most important when choosing a school for their child. “Academics” was the most commonly selected factor for charter school parents (29%) and Opportunity Scholarship parents (20%). “Ensuring a safe environment” was the single most important factor among ESA parents (21%), “Individual, one-on-one attention” was the most important factor for homeschool parents (22%), school assignment was the most important factor for public school parents (41%), and “religious environment/instruction” was the most important factor for non-choice private school parents (24%).

ESA and Opportunity Scholarship parents were more likely than non-choice parents to select “diversity” as the most influential factor when choosing a school. While 0-2 percent of non-choice parents cite “diversity” as being the most influential factor when choosing a school, 10 percent of ESA parents and 7 percent of Opportunity Scholarship parents selected “diversity.” ESA and Opportunity Scholarship parents were also slightly more likely to select “discipline” than non-choice parents. While 8 percent of ESA parents and 7 percent of Opportunity Scholarship parents selected “discipline” as being the most important factor, 4 percent or less of non-choice parents selected “discipline.”

School Climate

A substantial body of research has demonstrated a strong positive relationship between school climate and academic performance, socio-emotional development and other non-academic outcomes.15

One expectation for school choice policies is that parents will be able to access schools that maintain a culture for learning that suits the needs of their child.16 On our survey, parents described their perceptions of five key aspects of the learning culture at their child’s school.17 Generally, all parents give very high ratings to their child’s school for the components of school climate queried on the survey.

As shown in Figure 3, 91 percent of charter school parents and 85 percent of non-choice private school parents report that they are “confident that their child is safe at school,” compared to 81 percent of traditional public school and current Opportunity Scholarship parents, and 67 percent of current ESA parents. In the area of school discipline, current ESA parents (79%) and current Opportunity Scholarship parents (88%) are more likely than traditional public school parents (69%) to agree that the school uses appropriate strategies for disciplining students.

In reflecting on relationships in their child’s school, 90 percent of charter school parents say that staff make them feel welcome at school, a much higher percentage than traditional public school, non-choice private school, current ESA, or current voucher parents (79%, 83%, 81%, and 81%, respectively).

Ninety-one percent of charter school parents and 88 percent of non-choice private school parents report that their child has a good relationship with their teacher. Traditional public school, current ESA, and current Opportunity Scholarship parents are slightly less likely to report having that their child has a good relationship with their teacher (83%, 79%, and 83%, respectively).

Parents also assessed the degree to which schools invited them to provide “input on school programs and events.” Only 51 percent of traditional public school parents completely/somewhat agreed that their child’s school seeks their “input on school programs and events.” For all other parents, however, this rate was higher, ranging from 64 to 81 percent, with current ESA parents being most likely to completely/somewhat agree that their child’s school seeks their “input on school programs and events.”

Overall, parents with children in charter and private schools gave comparatively high ratings of their schools on the five measures of school climate, indicating that schools of choice may offer parents greater access to school settings that meet their child’s educational needs.

Parental Involvement

Over the past three decades, scholarly studies have consistently shown the benefits of parental involvement on a host of academic, socioemotional, and developmental outcomes for children.18 In theory, schools of choice are able to increase parent participation by leveraging their operational flexibility to address the needs of their school community and alleviate obstacles to parent participation.19 On the survey, we investigated this possibility by comparing rates of home- and school-based parental involvement. Figure 4 indicates participation rates in home-based parental involvement activities reported by the six groups of parents. We report the percentage of parents who indicated doing each activity “always” or “most of the time,” the two highest response categories.

Current ESA program parents and current Opportunity Scholarship parents are more likely than other parents to report “reading with or to their child” and “participating in a take-home reading program.” Seventy-two percent of current ESA parents indicate that they read with/to their child “most of the time” or “always,” and 79 percent of current Opportunity Scholarship parents indicate that they read with/to their child “most of the time” or “always.” Seventy-three percent of both current ESA parents and current Opportunity Scholarship parents report “participating in a take-home reading program” either “most of the time” or “always.” Traditional public school parents are the least likely group to report “reading with or to their child,” and homeschool parents are the least likely group to report “participating in a take-home reading program.” Traditional public school parents are less likely than parents from other groups to report “working on math or arithmetic with their child” either “most of the time” or “always.”

School choice parents, both ESA and Opportunity Scholarship, are also more likely to say they always participate in community service or do so most of the time compared to traditional public, charter school, homeschool, and non-choice private school parents. Current ESA parents stand out for being much more likely to report using online educational resources “always” or “most of the time” at 66 percent compared to only 46 percent of current Opportunity Scholarship, 40 percent of homeschool, 38 percent of charter school, 30 percent of non-choice private school, and 28 percent of traditional public school parents.

Parents in private and charter schools indicate higher home-based parental involvement than traditional public school parents, but the extent to which schools are responsible for these results is difficult to ascertain. It may be that the most active parents happen to be those who participate in school choice. School-based parental involvement, however, may offer a stronger indication of how different types of schools contribute to parental involvement since schools must play at least some role in enabling opportunities for school-based participation to occur.

Figure 5 compares reported rates of school-based parental involvement across the six groups of parents. As before, we report the percentage of parents who indicate that they participate “always” or “most of the time” in an activity. Current ESA parents and current Opportunity Scholarship parents report higher participation rates than their peers (with the exception of “reading/listening to communication from their child’s school,” and “communicating with their child’s teachers” where charter school parents report slightly higher participation).

The difference between current ESA and Opportunity scholarship parents and non-choice parents is most pronounced in the area of “attending family events/socials.” While 80 percent of current ESA and current Opportunity Scholarship parents indicate that they “attend family events/socials organized by their child’s school” “most of the time” or “always,” less than two-thirds of any other respondent group similarly indicate that they “attend family events/socials organized by their child’s school” “most of the time” or “always.” Current ESA and Opportunity Scholarship parents are also more likely to attend other school events, including school activities, and parent workshops/information sessions.

Current ESA and current Opportunity Scholarship parents are also more likely to report “volunteering at their child’s school.” Two-thirds (67%) of current ESA parents and half of current Opportunity Scholarship parents report “volunteering at their child’s school” either “most of the time” or “always.” This level of volunteering is much higher than traditional public school parents, where only 20 percent indicate that they “volunteer at their child’s school” either “most of the time” or “always.”

Overall trends depicted in Figure 5 suggest that parents with children in charter schools and private schools (including ESA and Opportunity Scholarship users) are more likely to participate in their child’s school than parents of traditional public school students.

How Do Education Savings Account and Voucher Programs Change Parents’ Sense of Involvement and Empowerment?

Another section of the survey measured the perceptions of program participants as to how their parental involvement changed as a result of enrolling in an ESA or Opportunity Scholarship program. Based on parents’ perceptions, results show marked growth in parent participation in their children’s academic lives at home and school for ESA and Opportunity Scholarship families. As shown in Figure 6, more than half of current ESA parents and current Opportunity Scholarship parents read and do math with their children “much more often” or “more often” than they did before enrolling in the choice programs. Most notably, 72 percent of current ESA program parents “read with or to their child” “ much more often” or “more often” since enrolling in the program. Only 10-16 percent of current ESA and current Opportunity Scholarship parents say that they read and do math with their children “less” or “much less often” after enrolling in these two programs.

For all activities, a higher proportion of current ESA parents than current Opportunity Scholarship parents indicate that they do each activity “much more often” or “more often” since enrolling their child in the program. Current ESA parents also reported higher rates of participation in most school-based activities (e.g., volunteering at school, attending workshops and information sessions, attending school socials, home-school communication, and parent-teacher communication).

Parents currently using ESA and Opportunity Scholarship programs were also asked a series of questions to determine if participating in these programs had altered their sense of empowerment. Parents indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed that participation in an ESA or Opportunity Scholarship program made them feel more in charge of their child’s education. On this item, over 70 percent of current ESA (73%) and Opportunity Scholarship (80%) parents reported feeling more in charge of their child’s education while less than one-tenth of ESA users (9%) and Opportunity Scholarship users (6%) reported not feeling in charge of their child’s education.

Over 60 percent of parents currently using ESA and Opportunity Scholarship programs also agree that these programs improved other aspects of empowerment and involvement (e.g., learning more about how their child learns, greater involvement in their child’s education, and increased confidence in their ability to choose what is best for their child). Taken together, these questions examining changes in parental involvement and empowerment indicate that ESA and voucher programs may contribute to greater parental involvement and empowerment.

Parental Satisfaction

Figure 9 illustrates parent satisfaction ratings in North Carolina among parents with children in traditional public, charter, homeschool, and private schools (i.e., ESA, Opportunity Scholarships, and non-program users). At least 75 percent of all respondent groups are satisfied with their child’s school. Eighty-three percent of charter school parents report being “somewhat or completely satisfied” with their child’s school, and 82 percent of non-choice private school parents, 80 percent of traditional public parents, and 79 percent of homeschool parents express the same. Seventy-eight percent of current Opportunity Scholarship parents report being satisfied with their school, which was slightly higher than the 76 percent of current ESA parents who feel similarly.

When asked how their current school satisfaction compares to their satisfaction with their child’s school prior to participating in the program, nearly three-fourths of ESA parents (73%) and Opportunity Scholarship parents (74%) said they are more satisfied. Only 6 percent of each group of parents said they are less satisfied with their child’s current school compared to the school they attended prior to participating in the programs.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020 changed how schooling was offered to students across the country. As such, we were interested to learn how the virus impacted NC parents and their children in particular, as this survey was fielded while many schools were in the final days and weeks of the 2019-20 school year.

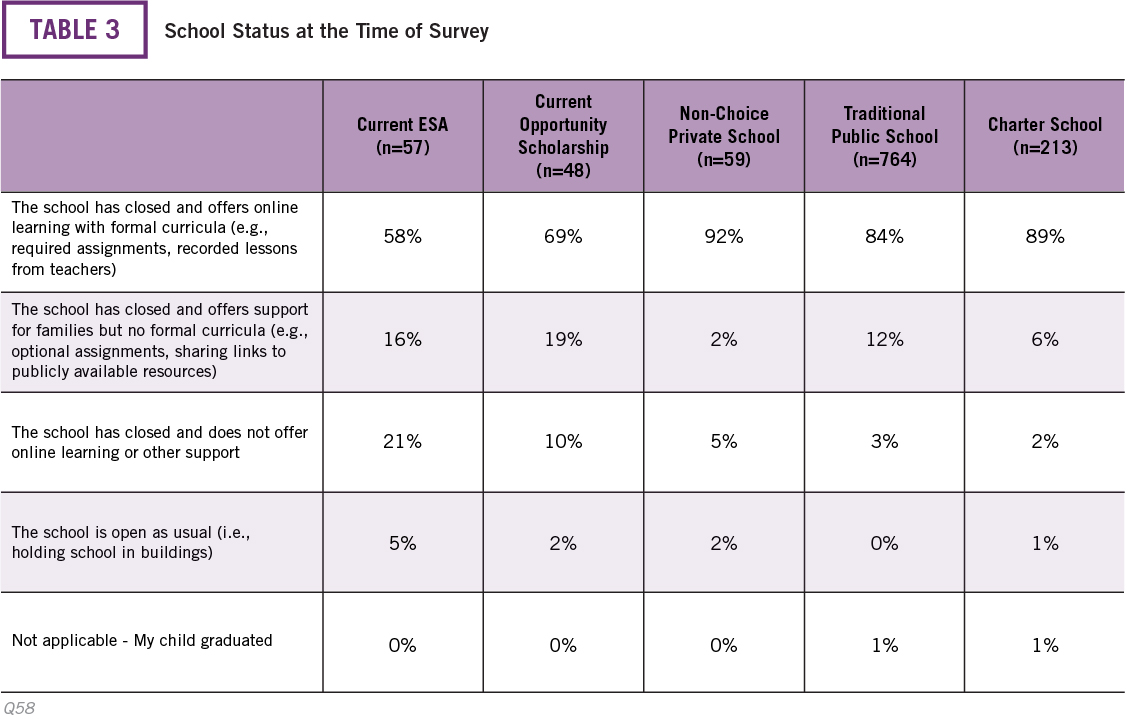

At the time of fielding, all parent groups most often reported that their school had closed and offered online learning with a formal curriculum, although schools of the current ESA (58%) and Opportunity Scholarship (69%) groups were less likely to report this as their schools’ status, compared to non-choice private (92%), traditional public (84%) or charter (89%) parents.

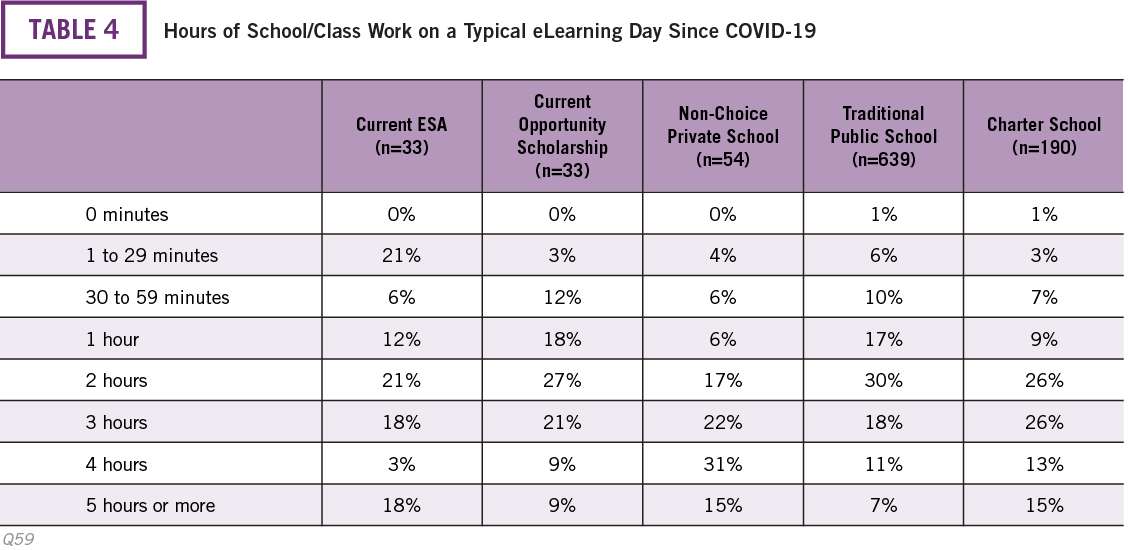

For those students who attended a school that offered online learning, most parents reported 2-3 hours of school/class work, with the exception of non-choice private parents, who most often reported four hours of school/class work on a typical e-learning day.

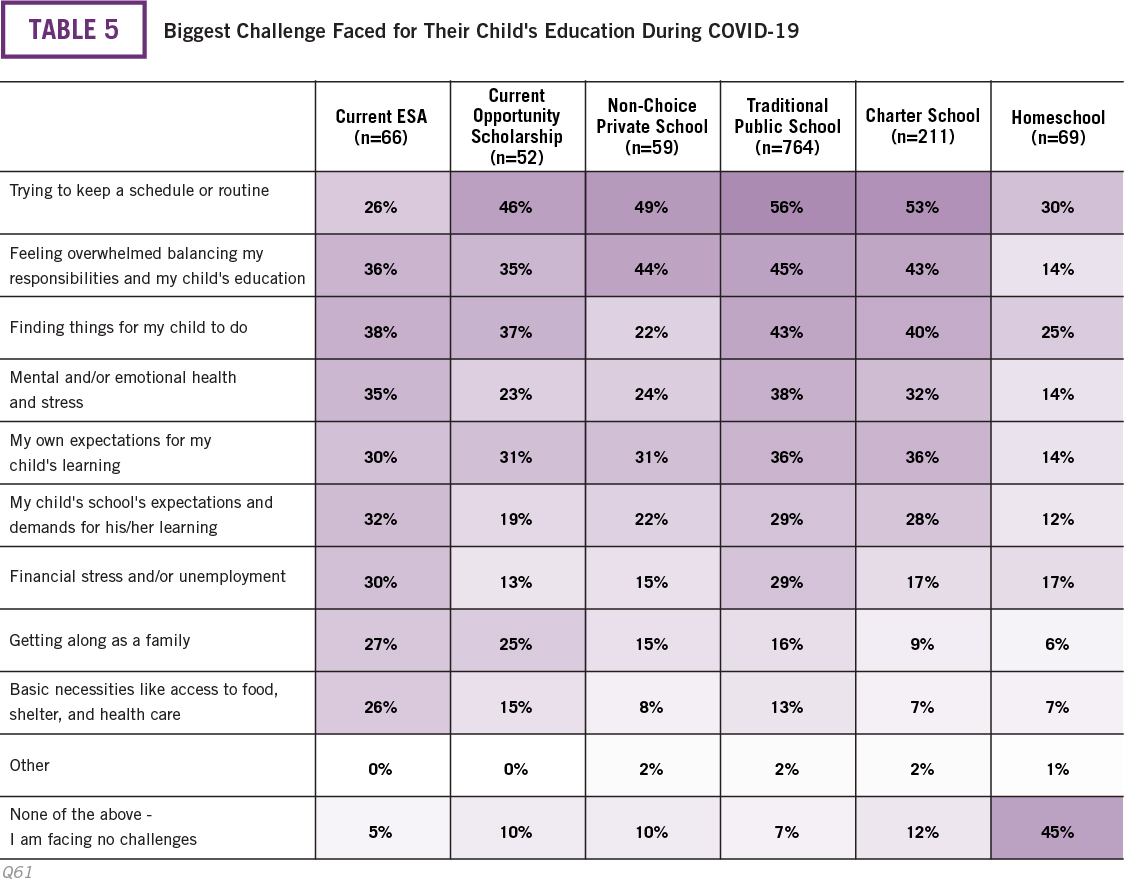

When asked what were the biggest challenges to their child’s education during the COVID-19 pandemic, unsurprisingly, 45 percent of homeschool parents reported no challenges being faced, compared to all other parent groups. Current ESA parents’ most often selected challenge was finding things for their child to do (38%), whereas current Opportunity Scholarship, traditional public, charter, and non-choice private school parents’ reported “trying to keep a schedule or routine” (46%, 56%, 53%, 49%, respectively) as the biggest challenge. Parents (with the exception of homeschool parents) also commonly felt overwhelmed trying to balance their responsibilities with their child’s education.

Conclusion

There is plenty of space for more research into the effects of North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarship and especially its special needs ESA programs, but this survey sheds light on North Carolina parents’ experiences with school choice and K–12 education generally. Parents reported having positive experiences with the programs. The same held true for various school climate metrics.

These results may be seen as intuitive when considering parents participating in the Opportunity Scholarship and ESA applied for and accepted funds and chose schools and educational services as necessary conditions for participating in the programs. But the reasons parents in North Carolina chose their children’s schools can have broader implications for educators and policymakers in the state who are tasked with catering to an increasingly diverse and evolving educational landscape.

This is especially true in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Learning online and away from the classroom are likely to continue to be a part of the K–12 education landscape in North Carolina. Along with choosing a schooling sector or type, parents are now having to consider their preferences pertaining to their children’s home-based academic routine and responsibilities. While North Carolina parents in general felt overwhelmed by the school closures and home-based education challenges brought on by the pandemic, sector and private school choice program differences of distance learning experiences yield some insight into how different types of education providers were able to pivot during a time of uncertainty.

Appendix 1: Survey Project and Profile

Title: 2020 North Carolina Parent Survey

Survey Sponsor: EdChoice

Survey Developer: EdChoice

Survey Data Collection & Quality Control: Hanover Research

Interview Dates: May 19-July 1, 2020

Interview Method: Web

Interview Length: 14 minutes (median)

Language(s): English only

Sampling Method: Panel and snowball sample

Population Sample: Parents in North Carolina

Sample Size: Current Education Savings Account Parents, N = 66 (partial and complete)

Current Opportunity Scholarship Parents, N = 54 (partial and complete)

Homeschool Parents, N = 69

Non-Choice Private School Parents, N = 59 (partial and complete)

Charter School Parents, N = 243 (partial and complete)

Traditional Public School Parents, N = 770 (partial and complete)

Margin of Error: Current Education Savings Account Parents = ± 10.58%

Current Opportunity Scholarship Parents = ± 13.31%

Homeschool Parents = ± 11.80%

Non-Choice Private School Parents = ± 12.76%

Charter School Parents = ± 6.28 %

Traditional Public School Parents = ± 3.53%

Response Rate: 0.07%

Weighting? No

Oversampling? Yes

Appendix 2: Methodology and Data Sources

The online survey solicited responses from North Carolina parents with a child in kindergarten through 12th grade during the 2019-20 or 2018-19 school years. These parents could have a child enrolled in a district (neighborhood) public school, a magnet school, a public charter school, a private school, or a child who is homeschooled. A portion of the private school parents participated in one of North Carolina’s educational choice programs—either the Education Savings Account (ESA) or an Opportunity Scholarship Program.

Responses to the survey were solicited primarily through a panel company, Dynata. The survey was launched on May 19, 2020. Screener questions were included in the survey to ensure that all respondents live in North Carolina and either currently have, or within the last two years have had, school-age children. By the time the survey closed on July 1, 1,273 complete and 332 partial responses were received.

In addition to the distribution of the survey through the panel company, a snowball sampling technique was employed to receive a greater number of responses from parents using one of North Carolina’s educational choice programs. Snowball sampling is a surveying method using a nonprobability sample to contact members of hard-to-reach or hidden populations. EdChoice shared the link to the survey to four organizations in NC, asking them to share the survey link with their families. By the time the survey closed on July 1, 170 complete and 146 partial responses were received from this snowball sampling phase of the distribution.

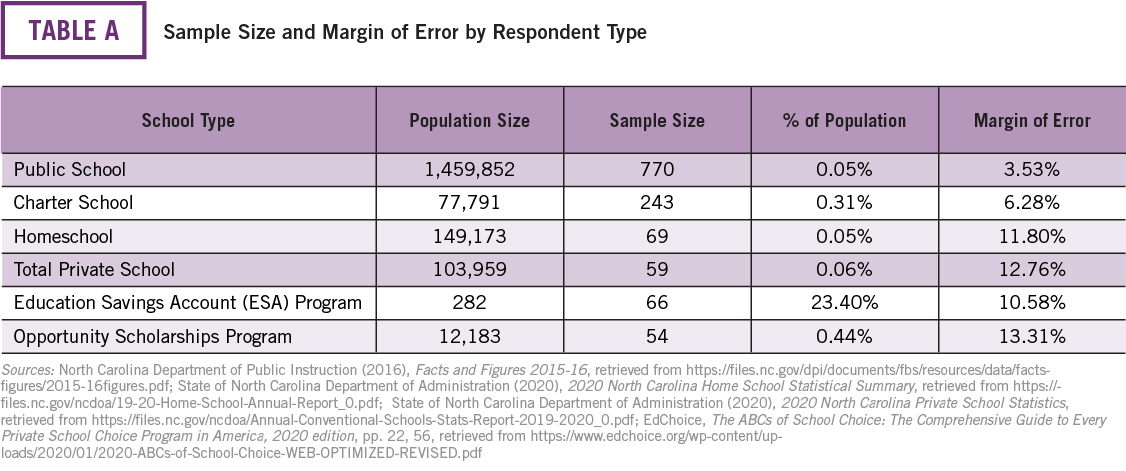

Taking the responses received from each of these two distributions together, a total of 1,261 parents responded to the survey and were included in the analysis after data cleaning. With roughly 1.8 million children enrolled in North Carolina schools or homeschooled in North Carolina, and assuming each parent responded to the survey for one child, the overall survey sample has a margin of error of about +/-2.759 percent.20 See Appendix for the margin of error for particular parent groups, based on the type of school their child attends.

Before analyzing the results of the survey, a portion of respondents were dropped due to not being qualified to take the survey (i.e., not being the parent of a school-aged child in North Carolina within the last two years), answering too few questions in the survey, or providing specious responses (non-panel respondents only). Non-panel responses were identified as specious for repeatedly selecting the same response across multiple matrix-style, Likert-grid questions. A total of 653 respondents of the 1,956 total responses received were dropped from the analysis.21 An additional 42 respondents indicate that their child attends a magnet school, and these respondents were not included in the final analysis.

Because we utilized a snowball sampling technique, the descriptive differences presented throughout the report are not necessarily representative of the population of parents in each school sector. Furthermore, the analyses are primarily descriptive and should not be interpreted as establishing any causal relationships.

In reporting results, we disaggregate responses within the private school sector into the following three sub-classifications: (1) current ESA user, (2) current Opportunity Scholarship user, and (3) non-choice private school parent.22 In other words, non-choice private school parents are parents with children in private schools who do not use an ESA or an Opportunity Scholarship. We separately report results for parents in the three remaining categories: charter school parents, traditional public-school parents, and homeschool parents.

Table A presents an overview of the sample of parent respondents to the survey. We highlight several notable differences across the five groups of parents in our sample (i.e., current ESA, current Opportunity Scholarship, Charter, Homeschool, Traditional Public, and Non-choice Private). Parents of program participants (ESA and Opportunity Scholarships) are more likely to have an annual household income of $100,00 or more when compared to non-choice respondents.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the North Carolinians that took the time to respond to the online survey. We are also grateful to Hanover Research for administering our survey and for data collection, quality control, and an initial take at graphics and text. We are very appreciative of the work of Michael Davey for making these pages look more professional and Jen Wagner for making us sound better than we would otherwise. Any remaining errors in this publication are solely those of the authors.

Additional PDFs

Questionnaire And Topline Results North Carolina Parent Survey

Endnotes

Authors’ calculations, National Center for Education Statistics, Table 203.20. Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools by region, state, and jurisdiction: Selected years, fall 1990 through fall 2028, last modified March 2019, retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_203.20.asp

Allison Redden and Kayla M. Siler (2020, May 20), Reflecting on a Decade of Investment: How competency-based education can help North Carolina achieve educational equity [Blog post], retrieved from EdNC website: https://www.ednc.org/perspective-reflecting-on-a-decade-of-investments-how-competency-based-education-can-help-north-carolina-achieve-educational-equity; FutureEd (2019, April 1), The Evolution of School Segregation: The North Carolina Story (FutureEd Interviews), retrieved from https://www.future-ed.org/the-evolution-of-school-segregation-the-north-carolina-story

The Nation’s Report Card, North Carolina Overview, accessed August 21, 2020, retrieved from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/profiles/stateprofile/overview/NC?cti=PgTab_OT&chort=1&sub=MAT&sj=NC&fs=Grade&st=MN&year=2019R3&sg=Gender%3A+Male+vs.+Female&sgv=Difference&ts=Single+Year&tss=2019R3-2019R3&sfj=NP&selectedJurisdiction=NC

Molly Osborne (2019, Janaury 25), Charter Schools in North Carolina: An Overview [Blog post], North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research, retrieved from https://nccppr.org/charter-schools-in-north-carolina-an-overview

North Carolina Division of Non-Public Education, New Conventional Schools School Listing – 2019-2020 School Year [Data file], accessed August 21, 2020, retreived from https://files.nc.gov/ncdoa/New-CS-Operating-2019-2020.pdf

WSOCTV (2020, July 2), Parents applying for home schooling in NC crash website, retrieved from https://www.wsoctv.com/news/local/parents-applying-home-schooling-nc-crash-website/Y3LJIFDPAZCZHE6YD4CTKDJ5NM; State of North Carolina Department of Administration (2020), 2020 North Carolina Home School Statistical Summary, retrieved from https://files.nc.gov/ncdoa/19-20-Home-School-Annual-Report_0.pdf; State of North Carolina Department of Administration (2020), 2020 North Carolina Private School Statistics, retrieved from https://files.nc.gov/ncdoa/Annual-Conventional-Schools-Stats-Report-2019-2020_0.pdf

EdChoice (2020), The ABCs of School Choice: The comprehensive guide to every school choice program in America (2020 edition), pp. 55–56, retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2020-ABCs-of-School-Choice-WEB-OPTIMIZED-REVISED.pdf

Anna J. Egalite, Stephen R. Porter, and Trip Stallings (2017), A Profile of Applicants to North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarship Program: Descriptive Data on the 2016-17 Applicants (OS Evaluation Report #3), Updated May 2019, retrieved from North Carolina State University website: https://ced.ncsu.edu/elphd/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/07/A-Pro-le-of-Applicants-to-North-Carolina%E2%80%99s-Opportunity-Scholarship-Program.pdf

Anna J. Egalite, Trip Stallings, and Stephen R. Porter (2020), An Analysis of the Effects of North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarship Program on Student Achievement, AERA Open, 6(1), https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2332858420912347

Anna J. Egalite, Ashley Gray, and Trip Stallings (2017), Parent Perspectives: Applicants to North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarship Program Share Their Experiences (OS Evaluation Report #2), retrieved from North Carolina State University website: https://ced.ncsu.edu/elphd/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/07/Parent-Perspectives.pdf

For more on this survey’s design and methodology, see Appendix 2

Andrew D. Catt and Albert Cheng (2019), Families’ Experiences on the New Frontier of Educational Choice: Findings from a Survey of K–12 Parents in Arizona, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019-4-Arizona-Parent-Survey-by-Andrew-Catt-and-Albert-Chang.pdf; Jason Bedrick and Lindsey Burke (2018), Surveying Florida Scholarship Families, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-10-Surveying-Florida-Scholarship-Families-byJason-Bedrick-and-Lindsey-Burke.pdf; Andrew D. Catt and Evan Rhinesmith (2017), Why Indiana Parents Choose: A Cross-Sector Survey of Parents’ Views in a Robust School Choice Environment, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Why-Indiana-Parents-Choose-2.pdf; Albert Cheng, Julie R. Trivitt, and Patrick J. Wolf (2016), School Choice and the Branding of Milwaukee Private Schools, Social Science Quarterly, 97(2), pp. 362–375, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12222; Heidi H. Erickson (2018), How Do Parents Choose Schools and What Schools Do They Choose? A Literature Review of Private School Choice Programs in the United States. Journal of School Choice, 11(4), 491–506, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2017.1395618; James P. Kelly and Benjamin Scafidi (2013), More Than Scores: An Analysis of Why and How Parents Choose Private Schools, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/More-Than-Scores.pdf; Julie R. Trivitt and Patrick J. Wolf (2011), School Choice and the Branding of Catholic Schools, Education Finance and Policy, 6(2), pp. 202–245, http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/EDFP_a_00032

Anthony S. Bryk, Penny Bender Sebring, Elaine Allensworth, Stuart Luppescu, and John Q. Easton (2010), Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago, retrieved from http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/O/bo8212979.html; William H. Jeynes (2011), Parental Involvement and Academic Success, retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=chDJBQAAQBAJ

Robert Bifulco and Helen F. Ladd (2006), Institutional Change and Coproduction of Public Services: The Effect of Charter Schools on Parental Involvement, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(4), pp. 553–576, https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muj001; Daniel Hamlin (2017), Parental Involvement in High Choice Deindustrialized Cities: A Comparison of Charter and Public Schools in Detroit, Urban Education, advance online publication, https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0042085917697201

M. Lee Van Horn (2003), Assessing the Unit of Measurement for School Climate through Psychometric and Outcome Analyses of the School Climate Survey, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(6), pp. 1002–1019, https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0013164403251317

- Eric Dearing, Holly Kreider, Sandra Simpkins, and Heather B. Weiss (2006), Family Involvement in School and Low-Income Children’s Literacy Performance: Longitudinal Associations Between and Within Families, Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4), pp. 653–664, https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022- 0663.98.4.653; Maurice J. Elias, Evanthia N. Patrikakou, and Roger P. Weissberg (2007), A Competence-Based Framework for Parent–School–Community Partnerships in Secondary Schools, School Psychology International, 28(5), 540–554, https://dx.doi. org/10.1177/0143034307085657; Anne T. Henderson and Karen L. Mapp (2002), A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement, Annual Synthesis 2002, retrieved from Southwest Educational Development Laboratory website: https://www.sedl.org/ connections/resources/evidence.pdf

Daniel D. Drake (2000), Responsive School Programs: Possibilities for Urban Schools, American Secondary Education, 28(4), pp. 9–15, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41064403;

Elizabeth M. Hassrick, Stephen W. Raudenbush, and Lisa Rosen (2017), The Ambitious Elementary School: Its Conception, Design, and Implications for Educational Equality, retrieved from https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Ambitious_Elementary_School.html?id=HZYtDwAAQBAJ

North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (2016), Facts and Figures 2015-16, retrieved from https://files.nc.gov/dpi/documents/fbs/resources/data/factsfigures/2015-16figures.pdf; State of North Carolina Department of Administration (2020), 2020 North Carolina Home School Statistical Summary, retrieved from https://files.nc.gov/ncdoa/19-20-Home-School-Annual-Report_0.pdf; State of North Carolina Department of Administration (2020), 2020 North Carolina Private School Statistics, retrieved from https://files.nc.gov/ncdoa/Annual-Conventional-Schools-Stats-Report-2019-2020_0.pdf

Of these dropped responses, 125 were dropped for being disqualified, 285 were dropped for providing too few responses, and 17 were dropped for providing specious responses. Note that the sample sizes for each phase of solicitation and school type reflect the final, cleaned data, with all errant responses dropped.

While ESA users and Opportunity Scholarship users are presumably private school parents, some respondents indicated that they were current ESA or Opportunity Scholarship parents and that their child does not attend a private school.