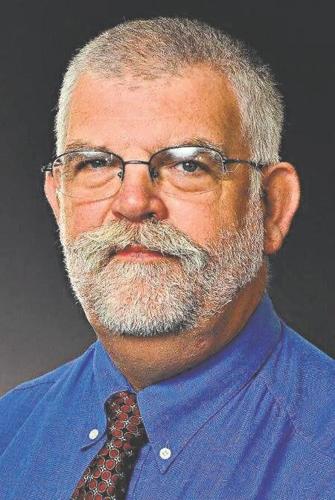

Farmers around the world are constantly faced with risks to their crops from weather and pests, but even more losses occur after crops are harvested. In fact, nearly a third of all the food produced worldwide — approximately 1.3 billion tons — is lost to food wastage each year. Dr. Angelos Deltsidis is an assistant professor in postharvest physiology in the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. His research investigates how preharvest factors and postharvest treatments affect the quality of fresh produce. He hopes to use this information to develop methods of preserving produce quality as it travels from the field to the kitchen.

“The quality of produce deteriorates from the moment of harvest all the way to the time you eat it in your home,” said Deltsidis, pointing out that consumers in developed countries waste almost as much food per year — 222 million tons — as the entire net food production of sub-Saharan Africa (230 million tons).

By making intentional decisions about food choices and use, consumers can contribute to reducing food waste. There are many factors that contribute to food waste and loss, including grade standards, producer economics, deterioration during storage, transportation losses and retail losses.

“There are a lot of reasons why we’re losing a lot of food here in the U.S., and some of it is because consumers expect everything to look perfect. In the U.S. and in the Western world, the customer is always right and we’re paying for that. Apples have to be perfectly round and large with no specks,” Deltsidis said.

“If a consumer doesn’t like this apple, they aren’t going to buy it, so the supermarket chain is not going to buy it from the supplier and the supplier won’t buy it from the farmer. In the end, if it is not perfect, the farmer will not harvest it. They will let it rot in the field or they will sort it and throw it away before it even gets packed. Because it does not meet that unrealistic standard, it would cost more to harvest and process than the farmer would realize in profit.”

The rise in popularity of direct-to-consumer distributors that specialize in produce “seconds” — such as Misfits Market, Imperfect Foods and Hungry Harvest — can offset this somewhat, he said, but a broader change in perception and expectation would go further to prevent food waste.

“If a product is unsafe to eat, that is one thing, but to reject something because it doesn’t meet expectations of what it should look like is just unrealistic. People need to understand that these are products that come from trees and plants — this is not a product that comes from a factory,” Deltsidis said. “Farmers can produce food that is safe and of good quality, but if it doesn’t make any money, they’re not going to harvest because they’re running a business,” explained Deltsidis.

“Our target is to make sure that the products we are producing maintain the best quality and are consumed as much as possible. We are not only innovating solutions in the lab, we are training harvesters in the field how to appropriately harvest the fruit or vegetables from the plant, how to appropriately transport it to the packing house, how to pack it, and how to make sure that it is held their appropriate temperature and appropriate relative humidity so it doesn’t lose water,” Deltsidis said. “We work with shippers on how it should be transported and the retailer on how it should be displayed and then we try to educate consumers on how to like store their products after they buy it.”

One contributor is at the end of the food supply chain — in our homes. Many people will throw away food that is still edible because there is a “best before” date stamped on the packaging. But packagers often use a conservative best-before date on a product because “they know people will throw it out and buy more,” he explained.

By making small changes in how we choose, purchase and consume food, each person can make a difference.

“We can’t control consumer behavior, but we can help educate people about reducing food waste,” Deltsidis said. “There’s education to do at each level, but it seems like better knowledge at the consumer level could have a lot of impact on all the other ones.”

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.