Municipal bonds – debt issued by state and local governments and some nonprofit institutions – are attractive to investors because the interest is generally exempt from federal income taxes. As a result, investors are willing to accept a lower interest rate than they would otherwise demand, and the issuers get lower borrowing costs. But recently, there has been a surge in issuance of taxable municipal bonds—that is, bonds whose interest is taxable to investors. Between January and November of 2020, $129.3 billion in taxable bonds were issued (31% of all municipal bonds issued over this period), up from $67.3 billion in 2019 and $25.1 billion in 2018. Here we explain the tax treatment of municipal bonds and explore what’s behind the recent surge in taxable municipal bonds.

What determines whether interest on a bond is taxable?

The interest on bonds issued by state and local governments is generally tax-exempt at the federal level, unless more than 10% of the proceeds are used for trade or business activities by nongovernmental entities, including leasing a public building to a private entity for business use. And nonprofits with 501(c)3 status, including colleges and hospitals, can issue tax-exempt bonds provided that no more than 5% of the proceeds are used for private business unrelated to the nonprofit’s charitable purposes. Regardless of whether the bond is taxed at the federal level, states independently determine whether they tax municipal bond interest. A 2008 Supreme Court ruling cleared the way for states and localities to exempt their own municipal bonds’ interest from their own taxes while taxing interest from other state and localities’ municipal bonds.

Who issues taxable municipal bonds and why?

In most circumstances, an issuer pays a higher interest rate to borrow when issuing taxable bonds than tax-exempt bonds. Local governments and nonprofits issue taxable bonds to finance projects that don’t meet the IRS’s tax exemption requirements, such as a sports stadium or a college student center that has a significant amount of space devoted to a bookstore managed by a national chain and/or a food court or restaurant. In addition, when interest rates are very low (like they are now), the overall advantage of tax exemption under low interest rates to issuers is very small, so entities that can issue tax-exempt bonds may choose to issue taxable bonds to avoid the IRS accounting requirements that accompany tax exemption.

During the Great Recession, under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), Congress created new types of taxable municipal bonds and expanded others. The interest on Build America Bonds, for instance, was taxable to investors, but through a combination of tax credits to investors and subsidies to local governments, the federal government reduced borrowing costs to close to tax-exempt rates. One objective was to broaden the market for state and local government bonds to investors, such as pension funds, university endowments, and foreign investors, who don’t generally pay federal income taxes and don’t benefit from the tax exemption. Broadening the market, proponents of Build America Bonds argued, would make it easier for state and local governments to finance their spending.

What are Private Activity Bonds?

Private Activity Bonds (PABs) use more than 10% of their proceeds for private business activities. While interest on some PABs is taxable, others are eligible for tax exemption so long as their proceeds are used for certain specific (or “qualified”) purposes, such as building airports, docks, or wharves. Interest on non-qualified PABs are federally taxable, and interest earned from PABs must be included in income when calculating the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), a tax that applies mostly to high-income individuals.

In addition, the IRS sets rules each year restricting the volume of tax-exempt PABs that can be issued by each state. For 2021, each state may only issue up to the greater of $110 per capita or $325 million. Therefore, very expensive projects that would be qualified PABs, such as building a new high-speed intercity train, may require issuance of some taxable bonds as well.

What fraction of municipal bonds are taxable?

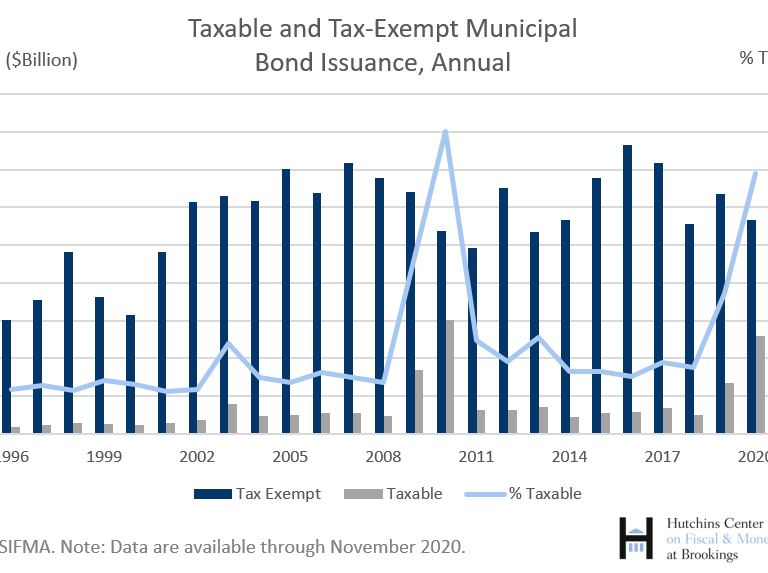

All municipal bonds were tax-exempt until the Tax Reform Act of 1986 established restrictions on the tax exemption of certain bonds. Between 1986 and 2009, the fraction of taxable municipal bonds remained between 3% and 7% of the total municipal bond market—except for a spike to 10% in 2003, when Illinois issued a $10 billion taxable bond to meet a pension obligation.

In 2009 and 2010, there was an increase in issuance of taxable municipal bonds because of the Build America Bonds program, which expired in 2010 and wasn’t extended.

Taxable bond issuance surged again in 2019. From August 2019 to November 2020, between 15% and 40% of municipal bonds issued each month were taxable. In October 2020, borrowers issued $45.2 billion in tax-exempt municipal bonds and $25.1 billion in taxable municipal bonds. (In comparison, corporations issued $152.9 billion in bonds in the same period.)

Why the surge now?

One big reason is a provision of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which prohibited the use of tax-exempt bonds for advanced refunding transactions, a refinancing maneuver we describe below. Previously, when interest rates declined, issuers of tax-exempt municipal bonds could issue a second tax-exempt bond to refinance their debt. Now, entities that want to use advanced refunding must issue taxable bonds.

Here’s how it works: Say a city issues a tax-exempt bond at a 4% interest rate. A few years later, interest rates drop, and now investors will accept 1.5% on a tax-exempt bond. Before 2017, the city would have issued a second tax-exempt bond, and essentially redeemed the outstanding portion of the initial bond, similar to a homeowner refinancing a mortgage. In practice, the city takes the proceeds from the second bond, and invests the funds in an escrow account. The interest earned on those funds pays the debt service on the first bond issued, and the city’s total borrowing costs fall.

With the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the city can only issue these refinancing bonds if they are taxable. However, current interest rates on taxable muni bonds are so low that the advanced refunding maneuver is still attractive. In the second half of 2019, nearly 80% of taxable bonds were used at least partly for this type of refinancing.

Who is buying taxable municipal bonds?

For most foreign investors, interest on tax-exempt bonds are taxable by their home country, so they aren’t likely to buy them. Tax-exempt bonds also are unappealing for tax-advantaged investments such as IRAs, 401(k)s, pension funds, and endowments. But taxable municipal bonds, with their higher yield, may be attractive alternatives in these cases.

Taxable municipal bonds also may be more attractive to people in lower tax brackets, for whom the tax exemption is less valuable. Assuming a 5% state income tax, someone in the 22% tax bracket will keep 83% of the interest on a taxable municipal bond; someone in the 35% tax bracket who would also owe state income taxes and an additional 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (the Obamacare/ACA tax) will keep only 56% of the interest. Depending on current interest rates, someone in a lower income bracket might find the (after-tax) yield on taxable municipal bonds appealing.

What’s the history of the tax exemption for municipal bonds?

When Congress introduced a federal income tax in 1861, municipal bond interest was taxed at the same rate as all other income. In 1895, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal income tax was unconstitutional, and added that a tax on state and local bond interest would violate the constitutional principle prohibiting the federal government from taxing the activities of states. The 16th Amendment gave Congress the right to impose a federal income tax, leading to the 1913 Revenue Act, the first iteration of today’s tax code. This law explicitly excluded interest from municipal bonds in income tax calculations. The taxation status of municipal bond interest remained largely unchanged until the 1980s, when a series of laws were passed increasing the regulation of municipal bonds and adding their interest back into some tax calculations for certain high-income individuals. This culminated with the 1986 law which defined PABs. The debate over the allowable volume of tax-exempt bonds has continued through to the present day in part because exempting interest from municipal bonds in tax calculations reduces federal tax receipts.

What does the future look like for taxable municipal bonds?

If interest rates on taxable municipal bonds remain low, the volume of taxable municipal bond debt issuance is likely to remain elevated over the next year. Although the advanced refunding refinancing mechanism is typically only cost effective one time (just like you don’t refinance your mortgage every year), low borrowing costs on taxable municipal bonds may be attractive for those projects that don’t qualify for tax-exempt financing—like the student center on a college campus.

Commentary

Why the surge in taxable municipal bonds?

December 21, 2020