This article is the latest installment of The Long View, AQ‘s look back at forgotten episodes in Latin American history.

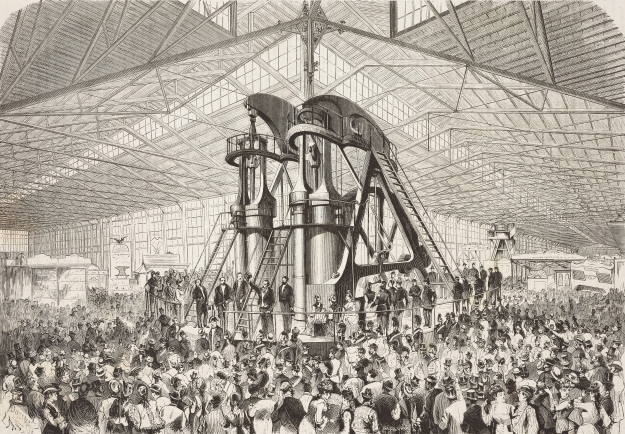

The day was May 10, 1876. The place: Fairmont Park, Philadelphia, and the grand opening of the Centennial Exposition celebrating 100 years of American independence. Honored guests Dom Pedro II and Teresa Cristina, emperor and empress of Brazil, had come to the United States to join President Ulysses S. Grant in celebrating the birth of a republic — the sort the monarchs would most certainly not welcome in their own country.

The opening of the first World’s Fair to be held in the United States was the highlight of a trip that became known in Brazil largely as the time Dom Pedro tested Alexander Graham Bell’s latest invention, the telephone. Delighted to see that the gadget “actually spoke,” the emperor pledged to buy one as soon as it was on the market, a promise he fulfilled.

Dom Pedro II’s travels were extensively documented by the New York Herald. Trailing him all the way from Brazil was reporter James J. O’Kelly, whose stories were largely responsible for spreading the image of Dom Pedro as a sympathetic and enlightened “citizen monarch” — while abroad, he insisted on calling himself Pedro de Alcântara, “simply a Brazilian citizen.” The emperor, however, was in the U.S. to do more than just project the image of a regular citizen intrigued by the latest scientific developments.

Beyond the telephone

At that time, World’s Fairs were true spectacles of modernity, as well as de facto trade conventions where participating countries would exhibit their best work in science, industry, arts, architecture and technology.

Brazil hoped to make a big splash at the Centennial Exposition, hoping to boost sales of its major commodity, coffee. A pamphlet prepared for the occasion highlighted the country “as an agricultural region possessing an extremely fertile soil” and Brazilians as “a peaceful, intelligent, and laborious people.” Dom Pedro was pleased. “We’ve made a good impression. … Our agricultural exhibit is an amazing sight,” he wrote in a letter to his daughter, Isabel.

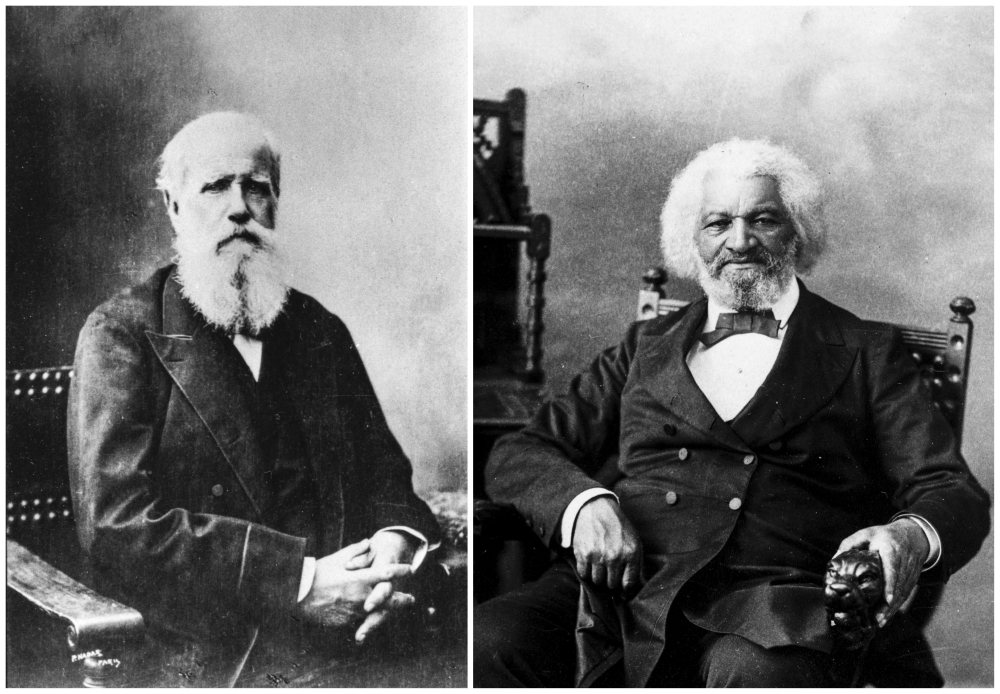

Dom Pedro II was included in this depiction of the 1876 Exposition. (Barberis from L’Illustrazione Italiana, No. 36/Getty)

Dom Pedro II was included in this depiction of the 1876 Exposition. (Barberis from L’Illustrazione Italiana, No. 36/Getty)

Selling coffee was one thing; presenting a positive picture of the country with the largest enslaved population in the Americas, however, was far more difficult. Brazil had been the final destination for half of all enslaved Africans brought across the Atlantic. But Dom Pedro’s representatives tried to paint a brighter picture by describing slavery as “imposed by the force of circumstances,” and “sure to disappear in a few years.” But it would certainly require a great deal of imagination for any spectator at the World’s Fair to believe their assurances that in Brazil, “slaves are humanely treated,” working “moderately, and, usually during the day, resting at night, when they receive religious instruction or amuse themselves.”

Did the friendly emperor manage to convince anyone in Philadelphia—slavery having been abolished in the United States just over a decade prior—that Brazil was a modern country, and slavery not a hindrance to doing business there? Did anyone believe the assessment that slaves were “so unprepared to receive their freedom,” that when freed they would choose to stay on plantations as laborers?

In O Novo Mundo (The New World), a Portuguese language newspaper published in New York, Brazilian editor José Carlos Rodrigues concluded that “this nefarious slavery not only prevents emigration to Brazil, but also (prevents) the agricultural industries’ access to foreign capital.” And yet, even though slavery was, in the language of the time, a “nefarious institution,” there were those who considered Brazil more advanced in race relations than the United States.

The Other Guest

Another participant at the opening ceremony was Frederick Douglass, an icon of American abolitionism. But he was almost barred from entering the gallery reserved for guests of honor. Eventually, a U.S. senator recognized him and he did join the group, causing the crowd in the gallery to erupt in applause. Douglass had barely taken his seat when the first chords of the Brazilian anthem started to play and applause broke out again—this time for the emperor, entering the same stage, arm in arm with Empress Teresa Cristina.

Did the “citizen monarch” Pedro de Alcântara even notice Frederick Douglass? At 58, the tall African American with long gray hair would have been easily recognizable. But the emperor didn’t seem to notice, or at least did not reference him in his diary or letters. O’Kelly’s articles didn’t mention him either.

That’s too bad. After abolition, Douglass, himself a former slave, made the fight against racism in the United States the focus of his work. Yet despite his own words that “no man of color is really free in a slave society,” Douglass expressed his admiration for Brazil more than once, avowing that it was a place where “white people had no disdain toward mixing or associating with blacks.”

Though Dom Pedro II didn’t leave any record of meeting Douglass, he certainly did not fail to spend time with Elizabeth Agassiz, the widow of his longtime friend, the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz. Indeed, it had been Mr. Agassiz who convinced Dom Pedro to visit the United States, a trip that he promised his friend would be a “triumphal march from one end of the country to the other.”

A zoologist and professor at Harvard who had died a few years earlier, Agassiz was a believer in scientific racism, which viewed miscegenation as the main contributor to the decay of the human race. Like Douglass, the naturalist also had a special interest in Brazil. But if for Douglass it was a place where “people of color, whether free or slaves, are not treated in the unfair, barbaric, and scandalous way they are here,” for Agassiz Brazil was the foremost example of the dire consequences of miscegenation.

Perhaps we should remember May 10, 1876, as the day Dom Pedro II missed his chance to meet Frederick Douglass, and with it an opportunity for Brazil to make a truly “decent impression.” As for Douglass, perhaps it was the day he realized that, at its core, Brazilian racism was not that different from the American version.

—

Grinberg is a professor of Brazilian history at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro