The question of which topics can and cannot be taught in Georgia classrooms was the subject of a state Senate hearing Monday afternoon.

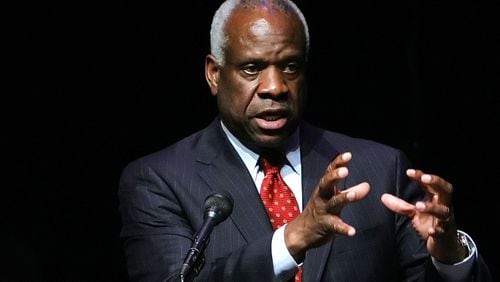

But first senators met for a fiery debate over whether to honor Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas with a statue on the state Capitol grounds.

Although the facts of Thomas’ life were not in dispute, senators still wrestled over his worthiness for the honor.

State Sen. Ben Watson, a Republican doctor from the Georgia coast, called Thomas’ journey from poverty in Pin Point, Ga., to Yale Law School, along with his work on the United States Supreme Court, “a life of tremendous achievement worth commemorating.”

But Democrats, especially Black lawmakers, disagreed.

“It is not that we have a problem that he’s a conservative or Republican,” state Sen. Nikki Merritt said. “We think he’s a hypocrite and a traitor and I’m going to tell you why.”

Merritt detailed Thomas’ opposition to affirmative action policies, despite his benefit from those policies, as just one objection.

State Sen. Emanuel Jones said he respected Thomas’ accomplishments but called his policies offensive. “We can’t whitewash history,” he warned.

“I wouldn’t want my little grandsons and granddaughters to come up here and be told the Clarence Thomas story.”

With Democrats opposed, and the Republican majority voting in favor, the Senate approved a statue for Thomas.

Many of the same senators who found little common ground in the morning went on to the Senate Education Committee for a hearing on SB 377, the bill from state Sen. Bo Hatchett that prevents teaching “certain divisive concepts” at all levels of Georgia schools.

The bill lists nine examples of the concepts that should not be taught, promoted, encouraged, or espoused, including the fact that one race is superior to another.

Also verboten in the bill is teaching that a person is inherently racist based on their skin color, or that the United States and Georgia are racist.

Most especially, students should not be taught that “an individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress” because of their skin color.

Hatchett, a Republican lawyer from Demorest, Ga., said his bill isn’t perfect, that American history can still be taught. He also said he was open to changes to the legislation, but even he seemed overwhelmed by the skeptical questions that came his way from Democrats.

State Sen. Sonia Halpern from Atlanta explained that her parents grew up in Jim Crow Mississippi, which she found distressing when she learned about it.

“If a student feels distress at the worst elements of our country’s history, is that cause for the school to lose its funding?” she asked.

The bill also says that while teachers can’t teach divisive concepts, they can “respond in an objective manner” to questions from students if they’re asked about them.

“You don’t think that has inherent conflict?”state Sen. Elena Parent asked. And who decides what an objective answer is, she wanted to know.

What about confederate imagery like a Rebel mascot, state Sen. Lester Jackson asked. Isn’t that offensive for some students? Shouldn’t those go too?

Hatchett warned that going after divisive mascots could be “very sensitive,” and suggested taking that up in a separate bill.

Democrats could have stayed all day hammering Hatchett with the dark and tragic details of Georgia history that are in danger of being forgotten if they’re not actively taught in schools. The poll taxes embedded in the state Constitution after the Civil War. The lynchings. The state-sponsored racism, frequently pushed by the members of the Georgia General Assembly in an era not so long ago.

It was the General Assembly in 1956 that agreed to keep Georgia schools segregated, even after the Supreme Court ordered the opposite. And lawmakers, almost 66 years ago to the day, approved a new state flag with the Confederate battle emblem at the urging of state Rep. Denmark Groover, a Democrat who said it “will show that we in Georgia intend to uphold what we stood for, will stand for and will fight for.”

Hatchett fielded more hypothetical questions about whether a teacher could say slave owners were racist. Or slave traders. Or lawmakers who supported Jim Crow laws in their day.

Hatchett said that, of course, a teacher can say that in the past the United States has been racist. “But when you say the United States as a whole right now, Georgia as a whole right now…that’s the lesson that we’re trying to prevent from being taught,” he said.

With time running short, the committee recessed and agreed to come back for more debate about what teachers in Georgia can and cannot teach going forward.

But if the state Senate made anything clear Monday, it’s that there is division inside their ranks over not just the past, but the present, too. Honoring Clarence Thomas was just the latest example.

Divisive concepts are, in fact, the work of the body. And they are the reality of our history. And the task of our society, including our schools, to deal with and hopefully move through and past.

I once had a conversation with a historian who said he wondered what would happen if all southerners began to call plantations what they really were, which was slave labor camps.

Would anyone of good conscience really want to have their wedding reception at a “Tall Pines Slave Labor Camp?” No. Likewise, what if we told ourselves, not just our children, the full story of Georgia’s history?

We’d be so much less likely to repeat it.

What our history means and how people feel about it is a critical conversation worth having. But it seems like a debate that belongs somewhere other than the Georgia General Assembly in an election year — somewhere like a classroom.