Credit: Photo courtesy of UGA Archeology

Credit: Photo courtesy of UGA Archeology

As modern humans struggle to adapt in the face of climate change, archeological research on Sapelo Island is rewriting the histories of native communities and their interactions with the environment on the Georgia and South Carolina coasts.

Researchers with the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archeology recently published a scholastic paper about how native coastal communities from 3,800 to 4,500 years ago adapted to a changing environment.

Using a variety of scientific methods to date oyster shells, Carey Garland, Victor Thompson and a team of researchers at UGA learned about the age, salinity of the water in which the oysters grew and when the shell was harvested. Providing greater insights into the conditions on Sapelo Island during the time period, the researchers also shed light on the eventual abandonment of the shell rings.

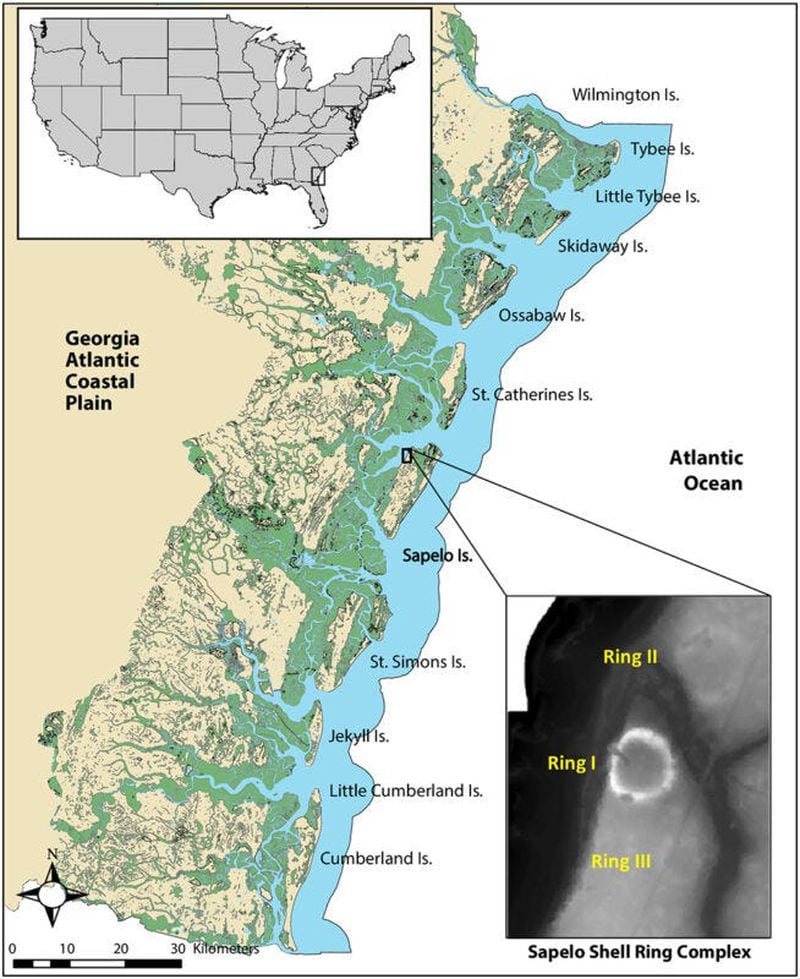

The shell rings, which can be 60 to 90 meters wide, or nearly 200 to 300 feet, were built by indigenous Muscogee communities using oyster shells harvested from the estuaries of Sapelo Island, which is about 70 miles south of Savannah. Oysters were a primary part of the communities’ diets and the shells have been one way archeologists and other researchers have looked back to learn about native coastal communities.

Credit: Photo courtesy of UGA Laboratory of Archaeology

Credit: Photo courtesy of UGA Laboratory of Archaeology

Many people think of archeologists on their hands and knees, shovels and brushes in hand, unearthing bones and clay pots which haven’t seen the sun in years. The shell rings on Sapelo Island, however, are just the opposite: Piled above the ground, Garland said they can reach up to about 3 meters high.

Garland, a post-doctoral researcher with UGA’s lab, said a lot of people think of native communities as nomadic hunter-gatherers, but the rings at Sapelo Island, and the research done on the oysters, show they were long-time dwellers on the coast.

Garland said the shell rings were previously thought to have been inhabited for many years until environmental changes caused communities to abruptly abandon the rings. With this new research, Garland said the oysters tell a story of continuous environmental change as well as community adaptation and resilience.

The research came about while Garland and Thompson were working on a much larger project collecting data from shells all around the region, and on Sapelo Island they became interested in three shell rings, one of which had oyster shells much smaller than the others.

“One thing we noticed is … there was some variation in shell size across the coast, but overall across time the shells got bigger, which kind of indicates sustainable shellfish harvesting practices,” Garland said.

Using radiocarbon dating and other methods to gauge the age of the oysters, Garland said they found a lot of variation. They also concluded the third, smaller ring was made later in time, around when the rings were abandoned.

About 3,800 years ago, around when the third, smaller ring was built and the shell rings were abandoned, Garland said research indicates sea level drops combined with a rainy season caused the oyster harvesting to become unsustainable.

Garland said he loves the interpretation side of his work — putting together a narrative from data is exciting — but Garland said another portion of completing the story is working with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, which now resides in Oklahoma but whose ancestral lands include Sapelo Island and much of the state of Georgia. He said they collaborate, provide additional context, information and review of the work.

“With this research, we argue that it is showing these villages represent resiliency and adaptation among these Indigenous communities, where they’re able to come together, work together and manage these fisheries over time even as the environment seems to get worse,” Garland said.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: UGA archeologists’ coastal research sheds light on native populations 4,500 years ago