An amateur’s snapshot of a tragic Eastern Airlines plane crash in the Clayton County woods; a journalist’s image of John Kennedy’s stump speech on an Atlanta stage; a commercial photographer’s black and white portrait of the inside of the 1950s Varsity, wall-to-wall with hungry customers.

The visual history of Atlanta is packed into boxes and stored in three different locations at Georgia State University, an archive of 10 million photographs, slides, negatives, videotape and movie film.

Credit: Georgia State University

Credit: Georgia State University

Tens of thousands images have been digitized and placed online. But millions exist only in some physical form, as a negative image on a strip of mutable plastic, or as a print, on porous paper, coated with a vulnerable emulsion.

Time, humidity and occasional carelessness are conspiring against this cache of knowledge. The archive “was forgotten about by everyone else in the university,” said Christina Zamon, who came to Georgia State in 2016. “But I’m not going to let us forget about it.”

As she spoke Zamon, head of special collections and archives, stood in a 2,000-square-foot underground room below a parking deck, where the bulk of the images are stored.

She was surrounded by boxes of prints and negatives, stacked on metal shelves. Draped over the tops of some shelves were sheets of plastic, to ward off any water potentially dripping from the ceiling. Arranged on the floor were cylindrical cloth bumpers stuffed with polyacrylate crystals, to absorb any moisture that might come up from below. An outdated HVAC system roared in the background.

Outside it was raining. Inside it was a bit sticky, 60 degrees and 62 percent humidity. Zamos would like to see it cooler and drier. She’d like fire suppression, modern HVAC, LED lighting, more room, and she has a new spot in mind, a 10,000 square-foot space underneath another GSU property.

A $48,691 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities will help get the project started, though it will cost an estimated $1-$1.5 million to get it totally outfitted.

Credit: From The Atlanta Journal-Constitution collection at Georgia State University

Credit: From The Atlanta Journal-Constitution collection at Georgia State University

The need for a new space is evident, not just from the improvised nature of the current facility in GSU’s Urban Life building, but because preserving photographs is essentially a dicey operation. Photographs and film seem determined to either destroy themselves or blow up their owners.

Many of GSU’s older negatives are on nitrate film, an unstable compound that can spontaneously burst into flames or even explode. In 1937, to mention just one incident, a 20th Century Fox vault in New Jersey caught fire because of gases produced by decaying film, destroying most of the company’s silent movies and killing one man.

Newer negatives are on acetate, a material with its own problems, namely “vinegar syndrome,” in which the emulsion buckles and emits a pungent sour smell. Zamon keeps examples of these in a box that visitors can handle and smell.

Even digital images aren’t forever images. Files can corrupt, said Zamon. Old formats become obsolete, hard drives crash, servers go offline. Photo preservationists must run like the Red Queen to stay in the same place.

There is also the simple challenge of organizing 10 million photographs. Human error can make some historic images hard to find.

There are probably numerous examples in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s collection of 8 million photos and negatives, an archive of images that was donated to GSU in 2010 and extends back into the 19th century. The filing system created by the newspaper was sometimes based on the personalities pictured, or on the day of the photo assignment, or on the subject matter, and therefore is not always easy to decipher.

Michelle Asci, who is charged with locating and digitizing requested images, recently discovered how easily a priceless image could be lost in the shuffle.

“I had received a request from a researcher and I was looking for images of the new Westside reservoir park from before, when it was a hard labor camp,” said Asci.

Tucked into a box of Westside negatives was an envelope marked “Woman pilots/old.” What did that mean? Old female pilots? Asci peered inside and saw a 4-by-5 negative bearing a familiar face and a familiar short haircut. It was Amelia Earhart, photographed during a 1934 trip to Candler Field in Atlanta.

Three years later Earhart disappeared. So did the negatives. “That’s how things get lost,” said Zamon. “This goes to the fact that there are millions of photographs, and to our inability to go through every single one, one by one. Inevitably somebody misfiles one.”

A visitor to the AJC archive in the Urban Life building experienced the newspaper’s curious filing system first hand. In an archival box, one of hundreds, was an envelope marked “Violent Death to WSB am radio.” Inside the envelope was a wirephoto of a half-naked victim lying in a pool of blood followed by a shiny black-and-white print of members of a country band, posing in the WSB studios, wearing 10-gallon hats and brandishing guitars — the Cowboy Yodelers.

And there you have the breadth of a newspaper’s photographic archive, which can cover everything from death to yodeling.

Credit: From The Atlanta Journal-Constitution collection at Georgia State University

Credit: From The Atlanta Journal-Constitution collection at Georgia State University

Elsewhere on the Georgia State University campus is the room that will probably become the new home of this unique archive. It is underground, nestled beneath yet another parking deck that was once attached to the Trust Company of Georgia’s 28-story building on Park Place.

The 10,000 square-foot room is wrapped in thick concrete walls and guarded by a chrome Mosler vault door, with hinges that probably weigh 50 pounds each. In this windowless room bank officials once stored documents and canceled checks.

Currently it is storing broken shelves and theatrical scenery from some medieval drama. (The theater department needed the space.)

“This is not good,” said Zamon, looking at a small puddle on the cement floor. Up above, conduit snaked across the ceiling — a possible source of the leak.

Zamon snapped a few photographs, then downloaded data off a small device that records the changing humidity and temperature in the spacious room. In that moment it was 65 degrees and 63% humidity. She would like to get it down to 40 degrees, but they’ll need a new HVAC system first.

The room is underground with walls that are two feet thick, so it is cool, even in the summer, but it is not currently an attractive address. One enters by walking past a pair of aromatic dumpsters and through a barrier of hanging strips of plastic, as if into a car wash.

Credit: From The Atlanta Journal-Constitution collection at Georgia State University

Credit: From The Atlanta Journal-Constitution collection at Georgia State University

Zamon hopes to secure additional funding, from the NEH and private supporters, to support this transition. The library also seeks followers who will “adopt” an imperiled negative, to cover the cost of restoration.

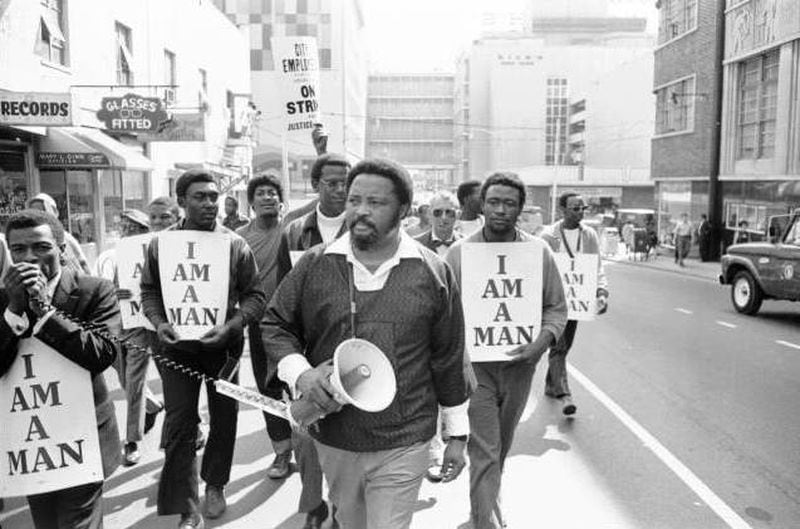

The university’s archive encompasses other collections of note: photos and films covering the history of the labor movement; photos from the alternative newspapers the Great Speckled Bird and Creative Loafing documenting the political and cultural ferment of the 1960s and ‘70s; photos (and recordings and personal papers) from Savannah native Johnny Mercer; the work of commercial photographers such as the Lane Brothers; and a unique collection from amateur photographer David Lennox, showing Atlanta during the late 1930s.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

During the pandemic many Atlantans spent time at home, cleaning out closets and store-rooms, and as a result donations to the library have exploded. As Zamon offered a tour around the 8th floor of Library South recently she walked past stacks of boxes in a hallway, part of an estimated 100,000 images just recently offered to the school.

All of these contribute to a wonderfully valuable storehouse of images that tell the story of Atlanta. In a library exhibit from 2018, GSU explains how this archival information helped prove the historic value of certain architectural gems, such as the Strand Theatre in Marietta and the Flatiron building downtown.

The exhibit’s point was to seek support for a permanent home for this archive, and for the personnel to keep it up to date.

But GSU’s treasure house of visuals does far more than protect old buildings. It records the way that we lived, the people in our world, the incidents great and small that make us what we are.

In Atlanta, a city with a short memory, that service is crucial.

About the Author

Credit: AJC, AP