In the years after the Civil War, orator and newspaper editor Henry V. Grady traveled the country to buoy a devastated South and promote Atlanta as its economic engine through speeches and editorials, writing, “The new South is enamored of her new work. Her soul is stirred with the breath of a new life.” He enticed Northern investors to the state and helped establish Georgia Tech.

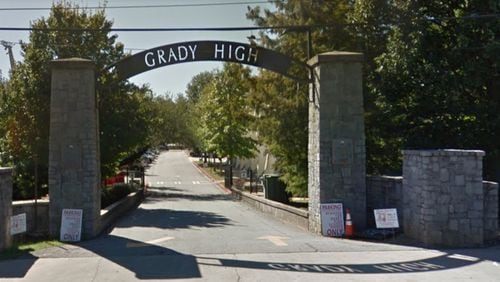

Those accomplishments — achieved before the peripatetic Grady died of pneumonia at 39 in 1889 — explain why Atlanta Public Schools named a high school for him 73 years ago. Now, that honor is about to be rescinded after fresh attention to Grady’s racial views, as revealed in his speeches, including one at the Texas State Fair a few months before he died where he said, "The supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the Negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards — because the white race is the superior race.”

Grady High is but one longtime Georgia institution whose namesake owned slaves or championed racist ideologies. A similar change is proposed for APS’ Joseph Emerson Brown Middle School, named for a secessionist governor and slave owner, and Forrest Hill Academy, an alternative school that commemorates Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Many cities, parks and schools around Georgia glorify historic figures from the Confederacy. In its 2018 deep dive into the issue, the Education Week Research Center found 140 K-12 buildings celebrating Confederates, two-thirds of which were in Georgia, Texas, Virginia, Florida and Louisiana. That number has been falling as more communities shed the Confederate honorees' names over their front doors.

However, even when communities agree a name ought to be vanquished — and that view is seldom unanimous and often acrimonious — battles can erupt over the replacement. For example, the erasure of Henry Grady’s name from Atlanta’s Grady High School hit a snag last week when the school board ceded to opposition to Ida B. Wells High School, the recommendation of a renaming committee appointed in March.

Born in 1862, Wells was a noted Black journalist and a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She documented lynching in all its horror, writing, “Our country’s national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob.”

A Change.org petition with nearly 2,000 signatures in opposition to renaming the school for Wells asserts she has no connection to Atlanta or Grady High and “seems to have been chosen to counteract the legacy of Henry W. Grady rather than to positively reflect our school and its students.” (One parent cited a more practical reason to nix Ida B. Wells High. She said kids are already corrupting it to “Ida B. High as a kite.”)

“She has no links to the community or our schools,” said Grady senior Lindsey Curtis, who, like many others speaking at last week’s school board meeting, urged letting students decide Grady’s new name. The board agreed to conduct a confidential, ranked-vote at the high school overseen by the APS administration.

“A lot of this started because students raised and elevated this to our attention and they had been doing it over many years," said school board Chair Jason Esteves.

The renaming committee, led by school board member Leslie Grant, included neighborhood and school representatives. Thousands of suggestions — emails, nominations, public comments, feedback from Grady classes and seven committee meetings — produced an initial list of 50 names, five of which were presented to the community in a nonbinding survey last month that narrowed the choices to three, Ida B. Wells, Midtown and Piedmont. The committee received 1,600 responses with the most support for Midtown, but chose Wells. Students will vote on one of these three choices.

“It was explicitly stated on several occasions by myself that this was not a whoever-gets-the-most-votes situation,” said Grant at the board meeting. While saying she believed the process was a fair one, Grant backed resorting now to a student vote. “What we must do is ensure our student voice is ultimately heard and elevated,” she said.

The decision now to defer to current Grady High students upset some alumni, who contend they deserve a voice. In the meantime, older graduates are expressing disappointment the school, long acclaimed for its academics, debate team and student publications, will lose the Grady name, which is shared by a South Georgia county, the state’s largest public hospital and the nationally recognized communications program at the University of Georgia. (The Grady name is also under fire at UGA, where some alums and students want to rename the J-school for its first Black graduate, Charlayne Hunter-Gault.)

As a 1956 graduate wrote on a petition in opposition to the name change, “I am proud of my high school and the man for whom it was named. Grady forever.”

Historians point out that the historic figures now under siege, while wrong on slavery, left some good in their wakes. Four-time Georgia Gov. Joseph Emerson Brown owned slaves and expanded his fortune on Georgia’s brutal convict lease system. He also co-founded the Atlanta Public School System, served as the first president of the APS school board, and, as a U.S. senator, advocated federal aid for public education.

Carter V. Findley, a 1959 Grady High School graduate and Humanities Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Ohio State University Department of History, said Grady’s stance on race should not be all that defines him. “His views on that subject are not what we want today, but that is not all there was to him, and he was — for better or worse — in step with his times," said Findley. “On race, he did believe in ‘separate but equal,’ but so did people all over the country, including the U.S. Supreme Court, right up until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954."

But those people all over the country didn’t include Black Americans, said Kathy Roberts Forde, an American journalism historian at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst who has researched Henry Grady. She is also co-editor of a book due next year, “Journalism & Jim Crow: The Making of White Supremacy in the New South.”

“The truth is that Black Americans fought Grady’s New South vision ferociously. And there were white Americans, even in the 1880s, who disagreed with Grady and the Supreme Court," she said. “Grady played an outsized role in crafting political, economic and social structures of white supremacy, and the ideology of white supremacy, in Georgia and across the South in the 1880s, the decade when Jim Crow began to be built.”

Forde supports stripping Grady’s name from the high school and the UGA journalism program. "Removing a name from a building doesn’t erase the past,” said Forde. “But it sometimes signals a new understanding of the past and a new effort to build a more inclusive community.”

·