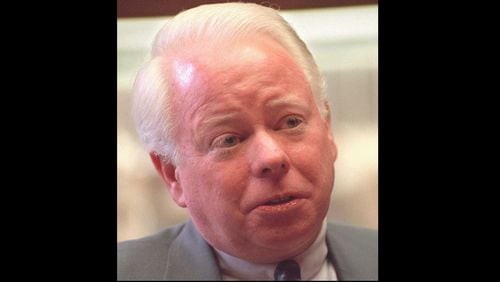

Nicholas L. Henry, who championed Georgia Southern University’s ascent from a Statesboro-based college to a comprehensive university while serving as its president from 1987 to 1998, died Tuesday. He was 80.

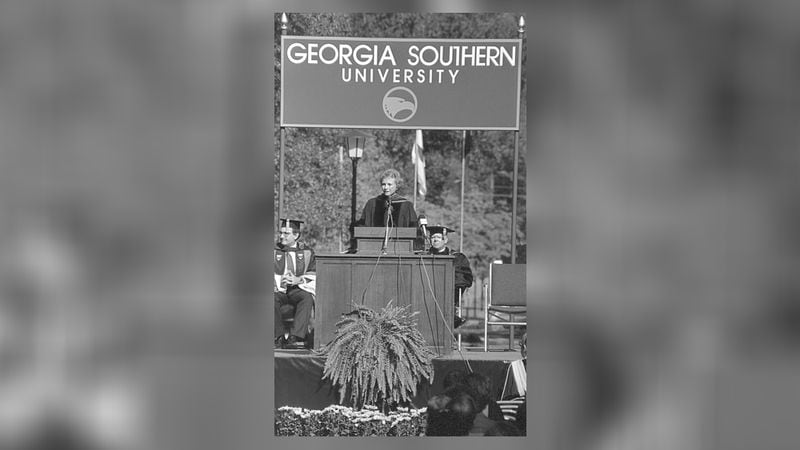

Henry was at the school’s helm in 1990, when the Georgia Board of Regents designated what was then known as Georgia Southern College as the state’s first regional university. The school celebrated the occasion with fireworks and, later, a speech by then-U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, whom Henry had gotten to know when he was a dean at Arizona State University and O’Connor was sitting on the Arizona Court of Appeals.

In his introductory remarks that day, Henry described the challenge of becoming a university and what the achievement meant.

“After years of privation, pursuit and progress, the people of South Georgia now have their university,” he said, according to an article in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “This campus symbolizes all that is best in South Georgia.”

Credit: via Georgia Southern University

Credit: via Georgia Southern University

Later in his life, Henry moved to Savannah where his support for South Georgia continued through his involvement in historic preservation.

University of Georgia professor Charles S. Bullock III had an office across the hall from Henry when he worked as an assistant professor of political science at UGA for several years in the early 1970s. Henry taught courses in public administration, preparing students for public sector jobs.

His career took him to Arizona State and then to Georgia Southern, where his successful push for university status was “a big feather in his cap,” Bullock said.

“I don’t know how many battles he had to fight to do it,” Bullock said. “It was a major accomplishment. I think part of his argument was that the whole southern half of the state did not have a university.”

State Sen. Billy Hickman, R-Statesboro, chair of the Senate Higher Education Committee, praised Henry for transforming Georgia Southern and “catalyzing its growth into a regional powerhouse that uplifted the entire Statesboro area.”

In a statement to the AJC, Hickman added: “Nick’s vision and dedication have left a lasting legacy on our community, demonstrating the profound impact of education on regional development. As someone deeply involved with Georgia Southern, I can attest to the indelible mark he has left on our community.”

Credit: Georgia Southern University

Credit: Georgia Southern University

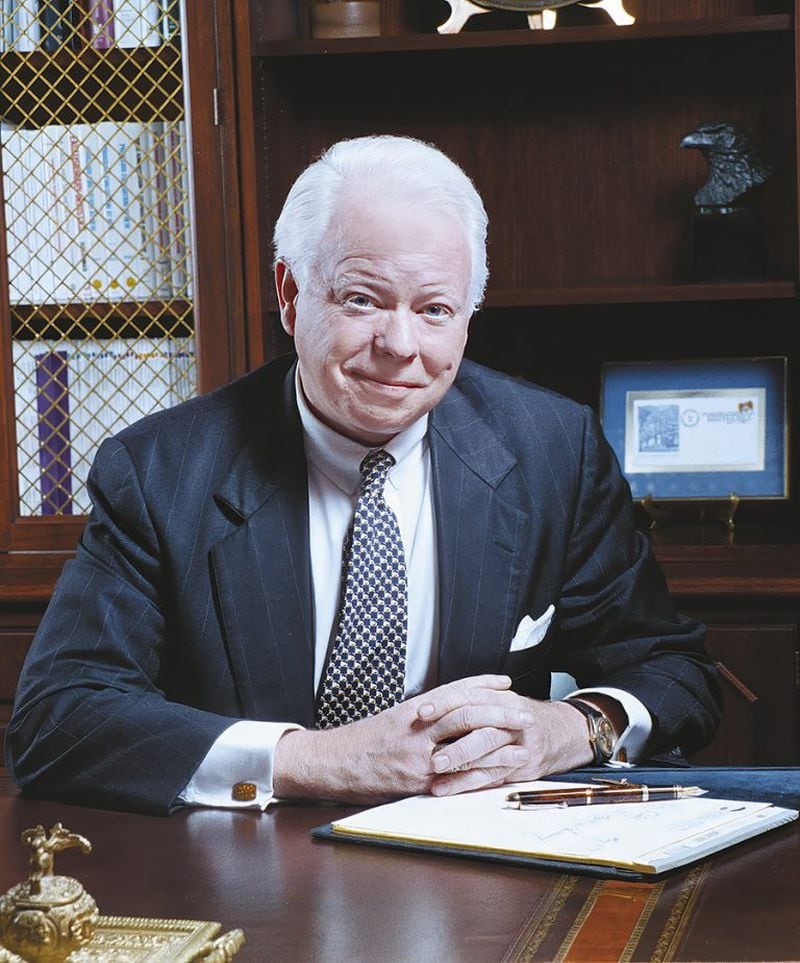

During Henry’s presidency, enrollment grew by roughly 5,000 students. That made the school “the fastest-growing university in the United States for seven years,” Georgia Southern’s current president, Kyle Marrero, said in a statement.

Marrero touted Henry’s efforts to boost the university’s research reach by supporting efforts to bring one of the world’s largest tick collections to Georgia Southern in partnership with the Smithsonian Institution and also establish the Center for Wildlife Education and the Lamar Q Ball, Jr. Raptor Center.

The flowers and greenery that adorn the main campus stem from Henry’s landscaping plan, and Henry also brought in $125 million for new buildings.

“It’s difficult to look around the Statesboro campus without seeing his influence at work,” said Marrero. “He raised the bar for what a university president could do for the community, region and state.”

In Henry’s final remarks to faculty in 1998, after he had tendered his resignation, he referenced disagreements with the Board of Regents over budget cuts. He also pushed the board to add an engineering school to the university’s offerings, saying those opposed “stand against a better life for South Georgians,” as reported by the student newspaper, the George-Anne.

An engineering college would come, eventually. In 2010, the board authorized Georgia Southern to offer bachelor degrees in civil, electrical and mechanical engineering.

Henry was awarded the title of president emeritus and professor emeritus of public administration at Georgia Southern.

In 1999, Henry and his wife, Muriel, purchased a home in Savannah, where he served for years on the Historic District Board of Review and then Savannah-Chatham County Historic Site and Monument Commission, of which he was a member until his death. Muriel Henry died in June.

Kristopher Monroe, the commission’s vice chair, said Henry supported ongoing efforts to remove Confederate monuments from the city’s iconic Forsyth Park as well as the recent renaming of Calhoun Square. The city removed the reference to John Calhoun, a former vice president of the United States known for his advocacy of slavery. The square now pays tribute to Susie King Taylor, a Black nurse and educator who opened a school for Black children in Savannah after the Civil War.

Monroe described Henry as a lifelong learner, who listened attentively and was always asking questions. He recalled attending Christmas parties at Henry’s home where the guest list was a diverse mix of people, “a who’s who of Savannah.”

“There are people who are in these esteemed positions, and they can be know-it-alls. He was the opposite of that,” Monroe said. “He was very humble and gracious.”

Melanie Wilson, executive director of the Chatham County-Savannah Metropolitan Planning Commission, said Henry was personable and passionate about historic preservation. He leaves behind a legacy in the city’s murals, art installations and its oldest places.

“If you (are) doing anything in the historic district,” she said, “that will make you think of him.”

A service for Henry will be held at a later date, according to Bynes-Royall Funeral Home, which is handling arrangements.