25 May 2021

Mulligan is golf jargon for an extra stroke allowed after a bad shot in a friendly game. Since mulligans are not permitted in tournament golf, when and how often they may be taken varies widely, but typically, one mulligan is allowed per round. And sometimes, mulligans are only allowed on drives from the tee. As to the word’s origin, there are a number of stories about golfers named Mulligan who gave their name to the practice, but none of these tales have any solid evidence in support, and it seems that mulligan actually made its way into golf from baseball, after a fictional long-ball hitter named Swat Milligan or Mulligan. It eventually came to mean a hard-hit ball, like one Milligan would hit. From there, it moved into golf, where it originally referred to a long drive from the tee. And from there, a second chance to hit a mulligan from the tee after a muffed drive.

The etymology of mulligan was unearthed by Peter Reitan and published in his blog in 2017. What I present here is mostly the fruits of his work.

Swat Milligan was the creation of New York Evening World sportswriter Bozeman Bulger in 1908. Milligan was the stuff of tall tales, a Paul Bunyan or John Henry of baseball. The earliest appearance of Milligan in the Evening World that I have found is from 26 May 1908:

I will say, however, that Milligan was regarded as the most scientific place hitter of the age. His marvellous [sic] ability can best be explained by recalling an incident in his career just after he quit the Willow Swamps and signed with the Poison Oaks. So many balls had been lost on Swat’s long drives that the club was almost in bankruptcy. Balls cost $1.25 each, you know. Something had to be done to curtail this expense or Milligan’s career would necessarily end.

The club finally hit upon the plan of having Swat hit all of his balls into the same spot and then corral them.

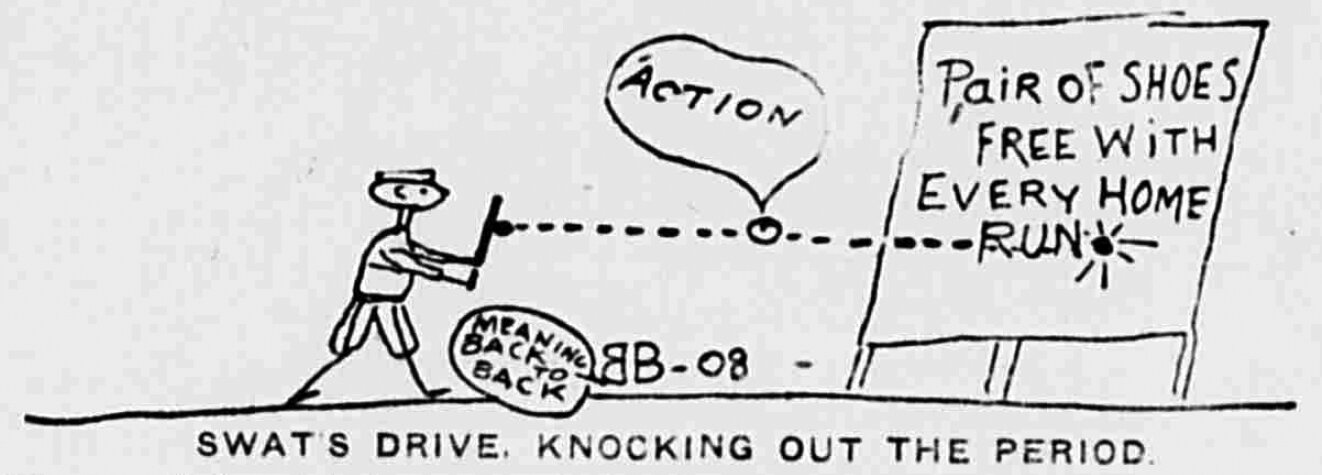

Two weeks later, on 8 June 1908, Bulger was telling this tale that illustrates Milligan’s prowess with a bat:

Bozeman Bulger,

Sporting Department, Evening World:

The fans out this way may want to know how many pairs of shoes Swat Milligan received for that wallop that brought in 1,278 runs? How many shoes did he wear out in running the bases, &c.f.

ADAM RENAL,

No. 165 West Sixtieth st.It is easy to observe, Adam, that you have are of a statistical turn of mind. For your information in that respect I will relate an incident that occurred on the first day of Swat’s arrival in fast company.

Milligan had just come up from Hitchingpost Hollow to join the Poison Oaks. He was practically unknown. As he entered the park on the morning before the game he noticed a sign offering a pair of shoes for every home run [....] They understood the rule that allowed a hitter to make as many runs as possible while the fielders were chasing the ball, but as no runner had ever scored over two runs at one time they had no fears [....]

The shoe wagons arrived on the grounds in the seventh inning, and as the bases were full Milligan was sent up with his big stick. Look carefully over the field he again saw the shoe sign. Just in the middle of it was a period painted green and about the size of a baseball. That steely glint came into the great batter’s eye and fandom knew that his mind was fixed.

Turning around like a whirling Dervish, Swat landed an awful rap, and the ball went whistling like a bullet straight to the shoe sign. It caught the punctuation mark as squarely as a die, and went tearing through it. So great was the force of the shot that it made no more noise than a bullet going through a door. The fielders rushed to the sign, but could see no trace of the ball. As the period was painted green they could see the green of the trees through the hole and [sic] though it was still there. Four hours later they gave up the search. But Swat—oh where was he?

Being ambitious in those days Swat tore around the bases so fast on the first twenty runs that he wore out a pair of shoes every two laps, and the shoe dealers began to open up the boxes. Relays of shoes were placed at first and third bases, and as Swat would wear out a pair he would jump into another, and keep on his wild career.

But Swat Milligan was too big a character to be confined to the pages of the Evening World. By 6 August 1908 sportswriters of the Trenton Evening Times in New Jersey were writing about his visiting and watching the Trenton team play, but the name was switched to Mulligan, either through error or to avoid potential copyright infringement:

To decide a bet will James Carmody state whether he had rubber in his hand when the fly bounded out of his grub hook in the early part of the game or was it just an ordinary glove. Swat Mulligan, who was a guest of Robert Bonham, says it would be impossible for a ball to bound off an ordinary glove in such a lively manner. Other well informed persons did not hesitate to make the statement that nothing ever got away from any reporter as fast as that ball bounced off Carmody’s hands.

And two days later the Trenton paper was calling batters who hit well in a game by the name:

Who is “Swat Mulligan?”

———

Magoon.

———

How many hits did Trenton get yesterday?

———

Five.

———

Who got four of ‘em?

———

Magoon.

———

Guess Magoon is “Swat Mulligan,” all right.

———

Perhaps you don’t know the story of “Swat Mulligan”?

———

Ask Bob Bonham, he tells it in his sleep.

And by the end of that baseball season, on 22 November 1908, the Duluth News-Tribune was giving Mulligan a mythic (and by today’s standards very politically incorrect) origin among the prehistoric Moundbuilders in what is now the American Midwest:

Those who have seen fit to doubt the existence of either Swat Milligan, the Peerless Poison Oaks or the Willow Swamp league, may put their fears at rest [....]

It is recorded that a man named Swat Mulligan, a paleface, appeared in the line-up of the Indiana Mound Builders on a certain bright day in June. At that time only 50 players were allowed on a side. It was in the seventh inning that Mulligan came to bat, and he mounted one of the mounds that all might see him work. An Indian pitcher by the name of Man-Afraid-His-Ribs-Might-Cave-In began to wind up with the wooden ball. He finally shot one over and Mulligan smashed it so clean that it looked like a broken clay pigeon. The fielders immediately began gathering up the splinters to use for firewood and the umpire tossed Man-Afraid-His-Ribs-Might-Cave-In another ball. This pitcher was called “Mana” for short by the fans. Again Mulligan tore the sphere to splinters.

Within a few years, Swat Mulligan memorabilia was available for sale. The Tacoma Times of 7 July 1911 ran this advertisement:

Swat Mulligan Dolls that you can’t break. Choice . . 98c

This was the “dead-ball era” of baseball. So, while Milligan’s power with the bat seems hyperbolically absurd today, it was even more so back then, when home runs were a rare occurrence. While the stories of Swat Mulligan are all but forgotten today, he was huge in his day, he was Babe Ruth before there was Babe Ruth.

And by the end of the decade, mulligan was being used to mean a hard-hit ball. On 12 April 1919, the Colorado Springs Gazette ran a story that compared baseball and cricket. It used mulligan to mean a hard-hit ball in cricket, but since there are few, if any, uses of mulligan in that sport, this particular instance probably reflects baseball slang of the era:

There is little about cricket that calls for brain work. An Englishman does not care for games that make any demand upon his mental faculties. At the bat he rarely figures “what is coming.” If it is a good ball “on the wicket” liable to knock the wickets down. If he misses it, he will carefully poke out his bat and just stop the ball. A fielder picks it up and returns it to the bowler. No running. And so on.

If it is a bad ball, “off the wicket,” he may take a “mulligan” at it and knock it over the fence, “out of bounds” they call it.

The term jumps to golf later that year with a pair of articles by sportswriter William Abbott in the Evening World in which he dubs two different golfers as the Swat Mulligan of the links. The first is on 13 June 1919 and refers to golfer Walter Hagen:

Famous as a long driver, a favorite Hagen trick is to let opponents lead him from the tee to the point where they start pressing in anxiety to rub it in. Then the Detroit wizard simply lets out a few kinks and its good night for the foolish golfer who thought he could outdistance the Swat Mulligan of the links.

The second, from 22 August 1919, refers to Dave Herron:

Woody Platt of Philadelphia came in for luncheon four holes down to Dave Herron of the Home club. The former, a newcomer to tournament golf, failed to get his strokes working in good shape against the long hitting Herron, who is the real Swat Mulligan of the links.

And the term is applied to the real-life Swat Mulligan, Babe Ruth, in the Evening World of 13 March 1920. The article refers to Ruth’s ability to hit a long ball in both baseball and golf in this headline:

LONG-RANGE HIT RECORD FOR BASEBALL AND GOLF RUTH’S CHIEF AMBITION

Famous “Babe” Has Natural Form for Walloping Home Runs, but on Links He’s Developed Special Style That Drives the Little Ball Over 300 Yards—Yankee Star Confident of Flashing New Swat Mulligan Stuff This Year in Both Baseball and Golf.

Ruth was not the only baseball player to take up golf in his spare time. And in the Detroit Free Press of 13 October 1931, we see mulligan applied to a do-over golf stroke for the first time. The passage is about New York Yankee Sammy Byrd playing in a pro-am golf tournament:

All were waiting to see what Byrd would do on the 290-yard 18th, with a creek in front of the well-elevated green. His first drive barely missed carrying the creek and he was given a “mulligan” just for fun. The second not only was over the creek on the fly but was within a few inches of the elevated green. That’s some poke!

Note that the general use here is that of a long drive from the tee, but the particular context is that of a handicap of a free stroke, so this is a transitional use of the word. Despite relying on a mulligan in this pro-am tournament, Byrd was an exceptional golfer who didn’t need the handicap. He would go on to win six PGA tournaments after he retired from baseball.

This appearance of mulligan in the sense of a do-over stroke antedates the earliest citation in the Oxford English Dictionary by several years. The one in the OED is from the Texas Big Spring Daily Herald of 5 May 1936 in an article about a staffer for President Franklin Roosevelt playing golf:

Following McIntyre around a few holes of golf frequently rewards the gallery with such irate remarks as “Nuts, I’ve had 10 strokes on this hole already; I’ll pick up.” He seems to find new hop on the next tee—that is, until his tee shot.

Another McIntyre-ism is the use of the “mulligan”—links-ology for a second shot employed after a previously dubbed shot. Most McIntyre “mulligans” are worse dubbed that the initial shot, however—which seems to serve as a psychological encouragement to the presidential attache.

So, that’s where golf’s mulligan comes from. It evolved from the name of fictional long-ball hitter in baseball, came to mean a hard-hit ball, and then transferred over from baseball to golf. From its initial golfing meaning of a long tee-shot, it came to mean a second chance to hit a long ball after muffing a drive. In other words, a golfer who screws up is given another chance to hit a mulligan.

I can’t leave the subject, however, without mention of the two golfers who are most often said to have lent their name to the mulligan. Both claimed to have been the originators, but only many decades after the fact.

Hotelier David Mulligan claimed to have coined it after taking a second shot in a regular game with his regular foursome at the Winged Foot Golf Club in Mamaroneck, New York. But he didn’t start playing with this particular foursome until 1932, a year after the term is recorded to mean a do-over stroke in golf. Furthermore, he didn’t claim to have originated it until 1952. Memories are malleable, and it is likely he mis-remembered an incident where the then-new slang term was used in jocular reference to his surname.

The second is John A. “Buddy” Mulligan, who worked as a locker-room attendant at the Essex Fells Country Club in New Jersey in the 1930s. He would occasionally be called upon to fill out a foursome and was given a free second shot as a handicap. He dates his claim, with no confirmable evidence, from the “mid-1930s,” again too late to be the origin. And he didn’t start making his claim until the 1970s, so his story shares that problem with David Mulligan’s. And in both of these claims it seems highly unlikely that a slang term from a handful of amateur golfers would quickly spread throughout the entire golfing world.

In contrast, the New York Evening World origin comes with verifiable citations charting the term’s development, a wide readership, imitations by other sportswriters, and a Swat Mulligan fad of large proportions, all firmly establishing the connection between mulligan and a hard-hit ball, before it ever comes close to a golf course.

Sources:

Abbott, William. “Jones is Leading Fownes by Single Hole in Golf Play.” Evening World (New York), 22 August 1919, 2. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historical American Newspapers.

Abbott, William. “Walter Hagen Enters British Open Tourney Scheduled Next Spring.” Evening World (New York), 13 June 1919, 22. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historical American Newspapers.

Bulger, Bozeman. “Scientific Batter! You Bet; Swat Milligan Was Real One.” Evening World (New York), 26 May 1908, 12. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Bulger, Bozeman. “Swat Milligan Put the Shoe Stores Out of Business with Home-Run Hit.” Evening World (New York), 8 June 1908, 8. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Drukenbrod, M. F. “Beaupres Step Some.” Detroit Free Press, 13 October 1931, 16. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Edgren, Robert. “Long-Range Hit Record for Baseball and Golf Ruth’s Chief Ambition.” Evening World (New York) 13 March 1920, 8. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historical American Newspapers.

“Golfers Try to Lower Marks.” Big Spring Daily Herald (Texas), 5 May 1936, 4. Newspaperarchive.com.

“The Man in the Grand Stand.” Trenton Evening Times (New Jersey), 6 August 1908, 11. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“The Man in the Grand Stand.” Trenton Evening Times (New Jersey), 8 August 1908, 11. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, March 2019, s.v. mulligan, n.2.

Reitan, Peter (a.k.a. Peter Jensen Brown). “Hey Mulligan Man! — a Second Shot at the History of Taking a “Mulligan.” Early Sports and Pop Culture History Blog, 8 May 2017.

“Ryner Malstrom” (advertisement). Tacoma Times (Washington), 7 July 1911, 6. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historical American Newspapers.

Sheridan, J. B. “Why Our Baseball Is Better Than British Cricket.” Colorado Springs Gazette, 19 April 1919, 12. Readex: America’s Historic Newspapers.

“Swat Mulligan Played on Moundbuilders’ Team.” Duluth News-Tribune (Minnesota), 22 November 1908, 4. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Image credit: Bozeman Bulger, The Evening World (New York), 8 June 1908, 8. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Public domain image.