Editor’s Note: Rebecca Cokley is the program officer for the US Disability Rights program at the Ford Foundation. She was the co-founder and director of the Disability Justice initiative at the Center for American Progress, served as the executive director for the National Council on Disability and oversaw diversity and inclusion efforts for the Obama administration. The views expressed here are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

I met Judy Heumann when I was 6. Having disabled women like my mom, my godmother Ann Cupolo Freeman and her best friend, Judy Heumann, in my life from a young age really had an impact on my sense of self. Their advocacy each had different styles and expressions, but the fact that they believed we had a right to equality, a right to be treated with respect and a right to be included in all things was something quickly embedded into my DNA.

As I got older and after I moved to Washington, DC, from California, our relationship changed. Judy was notorious for passing out my phone number to random disabled people she would meet on the street if she thought I could help them.

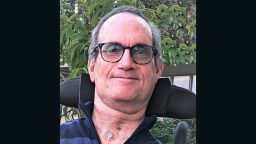

These are only a tiny fraction of my memories of Judy, a legend in the ongoing fight for disability rights in the United States, who died Saturday at 75. I remember watching former President Bill Clinton hop over a rope line at his own book signing at Politics and Prose when he heard she was waiting in line. While I worked at the White House as President Barack Obama’s lead on diversity, equity and inclusion, Judy was at the State Department advising then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

We talked often and found that while there were many things we agreed on, there were multiple times where we clearly were not in alignment on paths forward on pivotal issues. In many ways she went from being a shero to being my friend. But she was still a force.

Judy loved children. There was nothing she enjoyed more than going to the National Zoo with our kids. For so many of us, she was the disability nana or Bubbie. As we begin to mourn the loss of her, so many remembrances of her both inside and outside the disability community focus on her ability to connect with kids.

Judy always wanted to be a kindergarten teacher (and was denied). Remembrances of her this week have noted that she did become the first teacher in New York to work while using a wheelchair. I also think she very much wanted to be a mom — but the movement she loved came first and required some dreams be sacrificed. Young people were important to her, and she never got enough credit for setting aside dollars for the creation of programs to support the cultivation of the next generation of disabled leaders.

In 1977, Joseph Califano, President Jimmy Carter’s secretary of health, education and welfare, refused to sign Section 504 regulations of the Rehabilitation Act, which would prohibit discrimination for a number of marginalized communities, including the disabled, for any entity receiving federal dollars. This would include colleges and universities, nonprofit organizations and more.

Judy and other advocates were quick to apply pressure, engaging in acts of civil disobedience around the country, and most notably the sit-in of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare offices in San Francisco. Featured in the Netflix documentary “Crip Camp,” this was the longest occupation of a federal building in US history. It also served as a demonstrable show of force by a community previously framed by society and the media as weak, incapable and dependent. They were anything but that.

The actions taken by Judy and others not only opened the door to higher education for people with disabilities, but they also laid the groundwork for similar acts of activism into the next decade in advance of the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which expanded the civil rights protections for people with disabilities to include employment, public accommodations, transportation and technology.

Judy managed to balance being a diplomat with being an activist, with her most recent arrest coming in the summer of 2017 during attempts to overturn the Affordable Care Act.

Judy was ambitious, and that was seen as subversive for a disabled woman. Her dreams were both for herself and the community. Her work started outside the system, depicted in “Crip Camp,” but then she decided to be an infiltrator. She understood the importance of changing structures from the inside and the outside.

After working in the US Department of Education as the assistant secretary for the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services, she turned her attention to global disability rights work. She worked at the World Bank and then went on to advise the State Department.

Judy pushed the international human rights community to focus on issues facing people with disabilities when confronting the world’s challenges — whether it be war, climate change, pandemics, poverty or anything else. She ensured that disability was included in the Country Reports on Human Rights Practices and was the first disabled person to serve on the board of Human Rights Watch.

She came to the Ford Foundation (where I now work) as a senior adviser for disability inclusion, pushing the foundation, and philanthropy as a whole, to examine its cultural and structural ableism that led to only 3% of US-based human rights grant-making to go to disability advocacy.

Judy was often the first disabled person in whatever role she filled. Many were not used to people like us being in the decision-making position. We often talked about what it was like to be the only disabled person in a room — how isolating and segregated it could feel sometimes.

As a disabled person with multiple degrees, and a career in the halls of power, Judy had a day-to-day reality very different than that of most disabled people in the United States or around the world. She knew this and talked about it frequently. But the needs she had, for home and community-based services to keep her supported and thriving in her own home, with her husband and in community, still went beyond what 401(k)s or pensions can support. Like so many others, her life required that she never stop working.

Judy — in her life, in her work, in her relationships and in what she endured — served as a reminder of where our community has been, but also a reminder of where we need to go.