Yangyang Cheng examines a historical precedent for the technological competition between the US and China in quantum physics

At the entrance to the quantum physics and information lab at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), the country’s premier quantum research centre, visitors are greeted by a message in Chinese: “When I look back on my life, there were many hardships. My only hope is a prosperous homeland with advanced science and technology. We have done all we can, but our country is still poor and lagging behind. We need future generations of selfless and striving youth to carry on this work.”

The quote is from Zhao Zhongyao, who founded the department of modern physics at USTC in 1958. Born in the final days of the Qing empire, Zhao received his doctorate from the California Institute of Technology in 1931. His work was instrumental in the discovery of the positron, for which his colleague Carl Anderson was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics five years later. After graduation, Zhao returned to China but came back to the US in 1946 with two tasks. One was to observe nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll as one of the two representatives from the Chinese Nationalist government. The other was to learn accelerator technology and acquire equipment for particle-physics research.

Four years later, US authorities interrogated Zhao, detained him for months, and confiscated part of his materials before finally allowing him back to his homeland. The shift in the US government’s view of Zhao had little to do with his actions or beliefs. During his time in the US, the Nationalists lost the civil war to Mao’s Communists. The China that Zhao left had been a major US ally. The China he was returning to was now an adversary in the Cold War. Zhao could have stayed in the US or followed the Nationalist government to Taiwan, but his allegiance lay with the land of his birth and its people.

Great power rivalry

When I was a student at USTC in the late 2000s, the campus buzzed with excitement about an esteemed alumnus named Pan Jianwei, who had just returned from Europe to start a new group in quantum science. I moved to the US in 2009 for my PhD in particle physics and in the decade since have followed the news from my alma mater and from Pan’s group.

My pride in their scientific achievements, however, is tinged with growing unease as the frontiers of quantum computing and secure communications have become a new battleground of “great power” rivalry. Amid rising tensions between my birth country and my adopted home, Zhao’s words – and the story behind them – echo with lessons from history that are pressingly relevant today. Moved by the closing lines in Zhao’s memoir, Pan chose to display them on the front wall of his lab and has often invoked Zhao’s example in essays and speeches. Reading their words from an ocean away, I feel waves of emotion wash over me. Before the dizzying developments in recent years, the China of my childhood and for most of Pan’s life was impoverished and marginalized. For a people emerging from fresh memories of wars and famine, nationalism is a natural sentiment. It can be useful and even necessary to establish a shared identity.

But loyalty to one’s own has its limits. Out of patriotism, naivety, a desire for funding, or direct political pressure, a scientist can become part of the state’s propaganda and even complicit in the state’s actions. Chinese scientists of Zhao’s generation worked for a totalitarian regime and endured brutal persecution. As Beijing tightens its authoritarian grip and seeks new technology for power and control, scientific advancement also comes with a social cost. QuantumCTek, which grew out of USTC, is China’s first commercial provider of quantum-communications technology and works with police bureaus. While there is growing awareness of Beijing’s aggressions, the prevalent discourse in the West is not about ensuring ethical development and peaceful use of technology. Instead, the rhetoric from Washington and Brussels increasingly mirrors that of the Chinese government, where science is a tool of state power, and progress in other countries is perceived as threats to one’s own status and security.

Erecting barriers

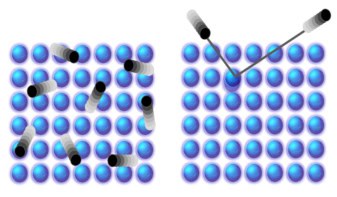

While export controls have traditionally focused on preventing weapons proliferation and human-rights abuses, in 2018 US Congress passed laws that curtail technology transfer and foreign investment to preserve America’s technological advantage. “Quantum information and sensing technology” is one of the 14 “emerging and foundational technologies” identified by the US Department of Commerce for controls. The European Union has also placed restrictions on non-EU participation in quantum-computing research, after a proposed ban was met with pushback from the academic community. A quantum revolution

As governments rush to assert borders and claim ownership over knowledge, the future of science appears fractured along national and geopolitical divisions. The dangers of a tech race lie in its faulty premise and misguided goal. The important question is not which country gets ahead but how progress is made and whose interest it serves. The recent demonstrations of quantum advantage by Google and Pan’s group respectively have been compared to the Wright brothers’ first flight. Exciting as it is, the history of aviation strikes a sombre note. Before they transported civilians and commerce, planes carried soldiers and bombs. Time and again, nascent technologies have been used for war.

Much of quantum science is still in its infancy. Applications are far on the horizon and the path is not predetermined. Humanity has a choice: to cling to parochial notions of country and creed, or to imagine a different kind of future that transcends artificial boundaries. I am reminded of my first quantum physics class at USTC where I was introduced to another way of seeing – a new concept of motion and space, classical barriers overcome.