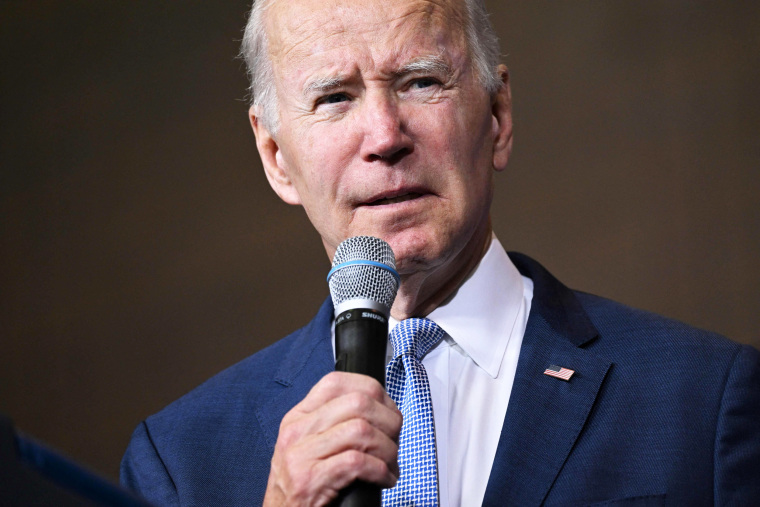

President Joe Biden’s press team has made no secret of their frustration with the way their boss is covered. And of late, the president is venting that frustration himself.

At a fundraiser in Los Angeles last week, Biden bemoaned the decline of traditional news reporting at the expense of the Internet. “There are no editors anymore,” he said. “How do people know the truth?” A week earlier when reporters — this one included — shouted over one another trying to ask Biden questions after a roundtable discussion on abortion, he turned to a participant and said with some exasperation, “Among the only press in the world that does this.

And it’s not just in unscripted, private moments. When Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act in August, he had the press in mind as he said that “too often we confuse noise with substance,” “confuse setbacks with defeat,” and “hand the biggest microphone to the critics and the cynics who delight in declaring failure.”

A White House long frustrated with the traditional news media filter has increasingly sought to go around it, finding ways through its digital strategy team and with non-traditional outlets to have the president get his message out.

During his West Coast swing last week, Biden sat down in person with actors Jason Bateman, Sean Hayes, and Will Arnett for a conversation that will air later this month on “Smartless,” one of the most-listened to podcasts. During a trip to the Detroit auto show in September he talked Daniel Mac — and his 12 million followers on TikTok.

As a senator and even vice president, Biden had long courted the media. He still ranks among the most frequent guests on “Meet The Press,” for instance, with 50 appearances. But people close to Biden say his increased skepticism is based in large part from the last two presidential campaigns, in which he sensed the coverage of the horse-race was out of step with what was at stake for the country.

In an interview with me weeks after Hillary Clinton lost to Trump, for instance, Biden bemoaned how much the race was dominated by controversies that “sucked all the oxygen” away from the key issues. And as one of nearly two dozen Democrats in the 2020 presidential primaries, Biden’s team constantly battled the conventional wisdom that the former vice president was not progressive enough to win the nomination, or later had the right strategy during a pandemic campaign to beat Trump.

“There has been a fundamental disbelief, particularly among the D.C., east coast press corps, in Biden’s vision, in his strategy, in his tactics, in his ability to do the things that he said he would do,” White House Communications Director Kate Bedingfield said in an interview. “There are reams and reams of headlines and tweets from reporters declaring his agenda dead, that he was out of date, he was out of touch with where the country is. And what’s happened is we’ve put together a historically successful set of legislative accomplishments that has defied those expectations.”

Day by day, Biden has come to share that view of some of his closest advisers, that the press corps simply just doesn’t “get” him and won’t give him a fair shake. But Biden has not exactly stiff-armed the mainstream press, Bedingfield noted. He just engages with them much differently than his predecessors.

Where President Obama had conducted 231 interviews through September of his second year in office, Biden sat for just 42, according to data compiled by Marth Kumar, an expert in the relationship between presidents and the press. But Biden had done 326 informal Q-and-A sessions with reporters through last month, nearly five times as many as Obama.

The bottom line view for this White House is there are diminishing returns in engaging in more traditional press interactions with members of the Washington press corps that in their view remain “fundamentally skeptical” of Biden’s performance. Beyond some of the more non-traditional formats for putting Biden out there, the White House has prioritized using members of their Cabinet and senior staff to do local and regional press interviews.

“It’s important to get out of that vicious 24-hour cycle of who’s up, who’s down that the DC press corps loves to get sucked into, and communicate broader, top line messages to the American people,” Bedingfield said.

Kumar, founder of the White House Transition Project, noted though that “while presidents complain of a hostile press, most frequently their coverage reflects political problems related to their policies, not press issues.”

Getting their money’s worth

As the Biden administration continues to closely monitor Russia’s provocative conduct in Ukraine, aides had to scramble to explain this eye-brow raising comment from Biden — that the world has “not faced the prospect of Armageddon since Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

“I don’t think there’s any such thing as an ability to easily use a tactical nuclear weapon and not end up with Armageddon,” Biden said.

Biden’s developed a reputation over decades in public life for being blunt and perhaps saying more than aides would prefer. “Nobody doubts I mean what I say, the problem is sometimes I say all that I mean,” he often jokes. But the setting of the “Armageddon” comment — a campaign fundraiser — is one in which he has often outdone himself.

The remark immediately brought back memories of two other notable remarks that created headaches for past campaigns. In 2008, then-vice presidential nominee Joe Biden made this prediction: “Mark my words. It will not be six months before the world tests Barack Obama like they did John Kennedy. … We’re gonna have an international crisis, a generated crisis, to test the mettle of this guy.”

It was a comment, a version of which he made at two separate west coast fundraisers, that added to strain between Obama campaign advisers and the newest member of the Democratic ticket.

And in the earliest weeks of his 2020 candidacy, Biden reminisced to a group of New York donors about his time in the Senate, recalling how he worked with segregationist senators like James Eastland of Mississippi. The point was to recall a time in which even lawmakers with fundamental differences on policy and principle still managed to work together, but was immediately seized upon by his rivals as an example of Biden being out of step with his seemingly fond recollection.

Biden would ultimately express “regret” for giving the impression “that I was praising those men who I successfully opposed time and again.”

Left (Out) Coast

As we closely track where Biden is — and isn’t — showing up to campaign, his just-completed West Coast trip offers an interesting test case.

Biden’s itinerary included campaign-style events with Democrats in bluer jurisdictions where Democratic candidates need to shore up their intra-party support — Tina Kotek, who’s locked in a tight three way race for Oregon governor, and Karen Bass, who is facing Republican-turned-Democrat Rick Caruso in the Los Angeles mayoral race.

Biden also stopped in Colorado to credit Sen. Michael Bennet, who’s reelection race has quietly grown more competitive, with being the driving force behind designating Camp Hale a national monument.

But he did not set foot in either of the two western states key to Democratic hopes of retaining control of the Senate — Arizona and Nevada. Biden’s never been to Arizona since taking office, in fact, and has only stopped in Nevada once to attend a memorial service for the late Senate Majority Leader, Harry Reid.

Biden advisors are particularly concerned about Nevada, where Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto is locked in a tight race with Republican Adam Laxalt. One adviser said that the economic headwinds facing Democrats across the country are particularly acute in the Silver State, whose economy is disproportionately dependent on tourism and thus suffered significantly because of Covid-19.