The Magazine for Ontario’s public school Principals & Vice-Principals. summer 2020 Volume 22 Number 3.

The Register SUMMER 2020 VOL. 22 NO. 3

T H E M AG A Z I N E F O R O N TA R I O ’ S P U B L I C S C H O O L

PR IN C IPAL S & V I C E - PR IN C IPAL S

Designing Schools of the Future Unlocking student wisdom

SUMMER OFFERINGS

YEAR IN REVIEW

VAPING

OPC Full-page thank you ad to thank all members across Ontario for their efforts to model learning in support of staff, students and school communities during this pandemic period.

Thank You To our Members across Ontario – we want to acknowledge

the extraordinary efforts you are making, above and beyond your normal roles, to model learning in support of your staff, students and school communities during this pandemic period. Your leadership and commitment to learning have been invaluable during these challenging times, and for that, we thank you.

Contents THE REGISTER : SUMMER 2020, VOLUME 22, NUMBER 3

Features 08 R isks of Vaping

By Peggy Sweeney

14 D esigning Schools of the Future By Dr. Bonnie Schmidt

28 Y ear in Review

By Protective Services Team

34 S eeking Reconciliation Champions By Minou Morley

22 R EGISTER REPORT Principal Well-being By Dr. Katina Polllock and Dr. Fei Wang

Columns 04 President’s Message 06 OPC News 07 Professional Learning

28

42 One Last Thought

Year in Review

Moving forward after significant challenges

Principals’ Picks 40 Mark Your Calendar 41 Review

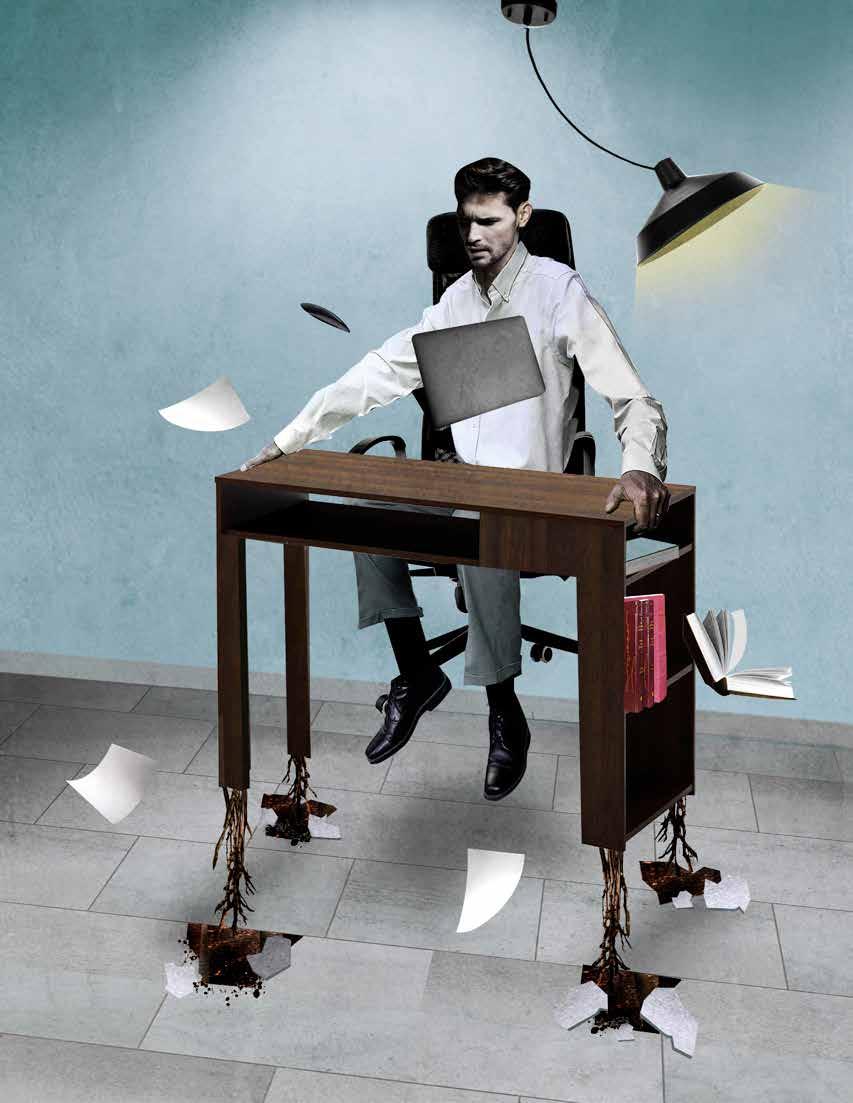

Cover Illustration by Adrian Forrow

The Register 3

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGEMESSAGE MIKE BENSON EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S President’s message

Advocacy

From the moment I became an administrator and joined the OPC, I have heard those questions about “what is the OPC doing for me?” or “when is the OPC going to put itself out there to be heard?” I believe one of the reasons, if not the main reason for these questions, is that we were all

part of a union prior to taking on the administrative role, and those unions often led with very loud voices. As such, the quieter voice of the OPC might be viewed as less effective, even when that is not the case, especially now. The OPC has come a long way in the past 20 years in terms of our Member advocacy. When our organization first began, we had very limited status and rights under the law. It took years for us to grow, not only in terms of the services we were able to provide Members, but also in terms of our role in bargaining and advocating for fair and appropriate 4 Summer 2020

employment conditions for administrators. It was not until 2012 that we were finally recognized by the Ministry of Education as the official bargaining agent for principals and vice-principals in the English public school system. This was a key achievement, not only in terms of bargaining rights, but also in positioning our association as a respected and valued partner in education. Another significant goal that our organization worked on in the early days was growing our political voice to ensure we would be heard and consulted with when key educational decisions were

being made. This took time, ongoing small key steps and an understanding that our reality is different from that of education workers who are part of the unions. Legislatively, we can’t strike, engage in work-to-rule activities or walk on or participate in picket lines. The school boards are our employer, and there could be employment consequences if we took part in any of these activities. As a much smaller organization (we have about 5,400 Members compared to about 130,000 members of ETFO and OSSTF), we do not have the financing to engage in public advertising campaigns that the unions often use to publicly raise their concerns and promote their bargaining positions. Our advocacy comes in the form of letters, public statements and meetings with government and other education stakeholder groups. This has made it more difficult for the public, and at times our Members, to “see” our support, since we are not on the front lines with teachers and support staff or taking out ads in media outlets. However, in the past year, with the encouragement of our Members, our Provincial Councillors and as a result of our increased profile as a critical partner in education, the OPC has found itself in a position where our opinion has been frequently sought after, and we have not shied away from making our voice heard (even when it has been in opposition to other education partners). We have met with the Minister, liaised with his office staff, spoken to other MPPs, written sev-

illustration: miki sato

Why it looks different this year

eral letters, released public statements and participated in media interviews. Advocacy can take many forms. Not all campaigns are as public and high profile as others. While we can’t control what ultimately ends up in a media story or what gets reported publicly, I can assure you that we do, and will continue to, advocate for our Members, our students and for conditions in schools that will ensure the success of all students.

Ontario Principals’ Council 20 Queen Street West, 27th Floor Toronto, Ontario M5H 3R3 Tel: 416-322-6600 or 1-800-701-2362 Fax: 416-322-6618 Website: www.principals.ca Email: admin@principals.ca The Register is published digitally three times a year by the Ontario Principals’ Council (OPC). The views expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the OPC. Reproduction of any part of this publication must be authorized by the editor and credited to the OPC and the authors involved. Letters to the editor and submissions on topics of interest to the profession are welcome. Although paid advertisements appear in this publication, the OPC does not endorse any products, services, or companies, nor any of the claims made or opinions expressed in the advertisement.

Be sure to read A Year in Review: Moving forward after significant challenges on page 28.

Peggy Sweeney, editor Laura Romanese, assistant editor Linda Massey, editorial consultant Dawn Martin, proofreader Allyson Otten, business manager

Stay connected with us and join our Twitter Chats using the hashtag #OPCchat

Art Direction and Design: Fresh Art & Design Inc. Advertising: Dovetail Communications Inc. 905-886-6640

The Register is the proud recipient of the following awards:

Nancy Brady president@principals.ca @PresidentOPC

TABBIES TABBIES TABBIES TABBIES

B

krw The Register 5

OPC NEWS

Happenings at the OPC ‌

Some of our Members joined us on February 26th for Pink Shirt Day to show support against bullying in schools.

Principals and vice-principals contributed photos of their schools for our wonder wall installment celebrating schools throughout Ontario.

OPC staff have been taking part in monthly team building activities to further strengthen our sense of community, team collaboration and office wellbeing such as Pancake Tuesday (L) and lunch time winter skating (R).

In January, President Nancy Brady welcomed visitors from Nord University in Norway.

6 Summer 2020

Winter SOQP candidates celebrate the completion of their course modules.

PROFESSIONAL LEARNING PRINCIPALS CANADA’S OUTSTANDING

Enhanced Professional Learning Our new name and new summer offerings

you

Y

ou may have noticed a change in our professional learning branding over the past several weeks. Previously known as Education Leadership Canada®, we are now Professional Learning. This change was made to be more representative of the work we do for you, and to be more meaningful to our program partners. We have been working diligently to continue to offer the relevant professional learning you have come to expect, as well as developing new offerings including monthly webinars and book clubs. We hope to continue to offer a variety of professional learning opportunities over the coming months. In addition to the usual Additional Qualifications offerings, our Professional Learning team is planning to offer a summer learning program that is varied both in topics and delivery method. There are currently 10 learning sessions planned for July and August: • July 6 (Ottawa) – International Mindedness for Linguistic and Cultural Inclusion • July 7 (Ottawa) – Culturally Responsive Leadership: Pathway towards empowering school culture

• July 8 (Toronto) – Mindfulness Everyday • July 9 (Toronto) – Sports Informed Leadership • July 13 (Online) – Relationships as the Catalyst for Learning and Development with Dr. Tranter (half-day) • July 6-17 (Online) Module – Recruitment and Retention in the FSL School • August 12-14 (Toronto) – Mentor-Coaching Institute • August 18 (Toronto) – Equity • August 19 (Toronto) – Leading Professional Learning in Your School • August 20 (Toronto and online) – Best Foot Forward for 2020–2021: Choices to support well-being with Dr. Karen Edge All of the details about these learning sessions, including registration links, can be found on our website. We are also partnering with ADFO, CPCO and VoiceEd Radio to bring you the “Rise and Learn Principal Chats,” a radio broadcast series during the week of August 16–20. Each morning at 9:00 a.m., school leaders from across the province will be able to tune into the live broadcasts. You can listen online from wherever you

are for one hour, or go back and listen to as many broadcasts as you like. Each day will offer a different learning topic: • August 17 – What Will 2021 Bring? A conversation with the three principal association presidents • August 18 – Effectively Navigating Cyberbullying • August 19 – Nurturing a Growth Mindset • August 20 – School Leadership Beyond Truth and Reconciliation • August 21 – Surviving September and Beyond Registration is not necessary. More details about the contents of each broadcast are available on our website. Finally, we will be offering an online summer book club for James Nottingham’s book Challenging Learning. James will join us as part of the August 19 Radio Broadcast with one or more Members from our book club. Our team is hopeful that the variety of summer offerings will meet your specific needs. If you have any suggestions for upcoming professional learning opportunities for the fall, please share them with us at learning@principals.ca. learning@principals.ca

The Register 7

Dangers, side effects and consequences that teens need to know about By Peggy Sweeney

Risks of vaping.

R I S K of Vaping

S Tobacco, alcohol, hard drugs. The list of illegal substances that young people try and use has expanded and changed over the years. The latest trend is vaping, and it has many health practitioners worried because the risks seem to be vastly misunderstood. It’s popular with young people because many of them think it is a safer product than tobacco. But that doesn’t appear to be true.

o, what is vaping? S While tobacco has been grown for about 8,000 years, it began to be chewed and smoked in cultural and religious ceremonies about 2,000 years ago. That has given scientists and the medical community plenty of time to research its negative effects and make that information publicly available. In 2017, it was reported that about 15 per cent of Canadians, or about 4.6 million people, smoked. In the early 2000s, a pharmacist from China named Hon Lik tried to kick his smoking habit. Finding that the nicotine patch didn’t stop his cravings, he sought to create a product that was similar to a cigarette but with fewer hazardous chemicals. His work resulted in an e-cigarette. Since then, many people have traded their traditional cigarettes for e-cigarettes, but the health hazards have not decreased. In fact, in many ways, e-cigarettes may be more dangerous. Today, we more commonly refer to the use of e-cigarettes as vaping. Electrical power is used to heat a liquid solution, causing the solution to become vapourized, and condensing it into an aerosol that is breathed in by the user through a mouthpiece. The vapour is often flavoured and can contain nicotine. Vaping devices are also referred to as mods, vapes, vape pens, e-hookahs or tank systems. They come in many shapes and sizes. Some are small and look like USB drives or pens, while others are much larger. The latest gadget is a vaping watch. The Register 9

10 Summer 2020

are engaging in it, and the lack of understanding among young people of its risks. Given the short time vaping has been in use, even the medical profession isn’t fully aware of all the dangers associated with it. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) refers to it as “tracking a moving target,” the challenge for researchers who are trying to understand the long-term health effects of e-cigarettes.

And it is not a consistent product everywhere it is sold. According to Dr. Robert Schwartz of CAMH, “We are seeing a range of devices, mechanisms and contents. Some e-cigarettes may deliver as much nicotine in 10 puffs as there is in a tobacco cigarette ... . Other e-cigarettes may contain little or no nicotine.” Dr. Schwartz and Dr. Laurie Zawertailo, also of CAMH, have also reported that

image: health canada

In the vaping substances that contain nicotine, the level of nicotine can vary widely, with some having more nicotine than a typical tobacco cigarette. Vaping products do not produce smoke, contain tobacco or involve burning. They can deliver nicotine to your body, causing you to crave it more and more, leading to addiction and physical dependence. For schools, vaping presents a challenge due to the increasing number of young people who

• carcinogenics and impurities are frequently detected in e-liquids • e-cigarette vapour may have cell-killing effects and • nicotine and other compounds are released into the environment and may result in passive exposure to others from e-cigarette use. How prevalent is its use among young people? The 2019 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey conducted by CAMH found that • more students are now vaping than using tobacco cigarettes • while 5 per cent of students reported smoking cigarettes, 23 per cent (about 184,000) reported using an e-cigarette • one in eight students use e-cigarettes daily or weekly • e-cigarette use for grades 7–12 students doubled between 2017 and 2019 • 2 per cent of Grade 7 students use e-cigarette products, rising to 35 per cent for Grade 12 students • youth (15 to 19 years) and young adults (20 to 24 years) have the highest rates of trying vaping • over half of the young people who vaped in the past year used a product containing nicotine. These statistics should be troubling to everyone. One of the challenges is the unknown. Nicotine is a highly addictive substance with many side effects. Children and youth are especially susceptible to its harmful effects. Vaping with nicotine can lead to dependence, addiction, memory and concentration impairment, reduced impulse control and cognitive and behavioural problems. And teens may become dependent on nicotine with lower levels of exposure than adults. While they may think e-cigarettes are safer and less harmful than tobacco, they don’t seem to understand that they are vaping nicotine and its side effects. Nicotine can also alter brain development, a concern since brains are still developing during the teen years.

fa c t s 3 per cent of students in grades 7–12 have tried an 2 electronic cigarette V aping devices can also be used for other substances like cannabis V aping devices come in a variety of shapes and sizes; some resemble a USB flash drive L iquids can have high levels of nicotine and come in a variety of flavours V aping may not leave a lingering or identifiable smell A dd-ons like vinyl skins or wraps can make these items harder to recognize V aping products have many names such as e-cigarettes, vape pens, vapes, mods, tanks and e-hookahs V aping can increase your exposure to harmful chemicals T he long-term consequences of vaping are unknown V aping nicotine can alter teen brain development Source: Health Canada

Another big challenge is the marketing of these products. Juul, the American company that has about three-quarters of the US e-cigarette market, claims that it is in the business of helping adults quit smoking. But researchers with Stanford University looking at the impact of tobacco advertising found the company’s marketing was “patently youth-oriented.” The device was designed to look sleek and attractive, particularly to young people, one that could be mistaken for a USB drive and could fit into the palm of your hand. The pods come in a variety of colours and flavours, including cucumber, creme brûlée, mango and tobacco. Juul hired influencers – young people with large followings on social media – to promote its products and distribute them for free at movie and music events. Ads used themes like pleasure and relaxation, socialization and romance, and style and identity to promote the product. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids noted that, “It’s impossible to review the data [in the paper]

and conclude anything other than the marketing is the major reason this product became so popular among young people.” Today, the products are sold, promoted and advertised in corner stores and gas stations. It’s hard to go into or pass one of these retailers without seeing the product prominently on display. In Ontario, the Smoke Free Ontario Act prohibits smoking and vaping in any public or private schools’ indoor space, outdoor grounds including playgrounds and sports fields and within 20 metres of a school. The prohibitions also include child care centres and early years programs on school properties. That hasn’t stopped many students from vaping near and on school property. Parents, educators and medical practitioners are concerned about the misinformation teens have and the ease with which young people can buy vaping products. In December 2019, physicians writing a report in the Canadian Medical Association Journal identified a new pattern of illness related to vapThe Register 11

IIIII TALKING WITH YOUR TEEN ABOUT VAPING

T H

A TIP SHEET FOR PARENTS

Components of a Va

BEFORE THE TALK: GET THE FACTS Vaping is not harmless

Tank or res (for vaping

Although not all vaping products contain nicotine, the majority of them do, and the level of nicotine can vary widely. Some vaping liquids have low levels, but many have levels of nicotine similar or higher than in a typical cigarette. Quitting vaping can be challenging once a teen has developed an addiction to nicotine. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms can be unpleasant.

› Vaping can increase your exposure to harmful chemicals.

› Vaping can lead to nicotine addiction.

› The long-term consequences of vaping are unknown.

› It’s rare, but defective vaping products (especially batteries) may catch fire or explode, leading to burns and injuries.

Mouthpiece

Contents of Vaping L

Vaping nicotine can alter teen brain development.

Risks of nicotine

Nicotine is a highly addictive chemical. Youth are especially susceptible to its negative effects, as it can alter their brain development and can affect memory and concentration. It can also lead to addiction and physical dependence. Children and youth may become dependent on nicotine more rapidly than adults.

Even if a vaping product does not contain nicotine, there is still a risk of being exposed to other harmful chemicals.

How it Works: From l

1 Vaping liquid, which chemicals, is heate become an aerosol

What schools can do S hare this article with your school community Organize a presentation/ parent info night Put posters up in your school Ask someone from the local board of health to come in as a guest speaker Obtain information materials from local board of health or Health Canada

12 Summer 2020

2 The aerosol is inhaled through the mouth and lungs where it is absorbed into the bloodstream

3 The remaining aerosol is exhaled

ing. Dr. Karen Bosma, the paper’s lead author, ment to tighten up regulations for vaping use said “We wanted to put this case out there as and sales to be more in line with current toa warning to people. Because these chemicals bacco regulations. The Board wants to see all that are in e-cigarettes have not been extensively flavoured vaping products banned at stores tested, and we don’t know a lot about how they where “minors have access.” might harm the lungs.” In January 2020, the Heart and Stroke FounA previously healthy teenager who had vaped dation of Canada called on the provincial govdaily for five months was diagnosed with a ernment to increase taxes on vaping products to form of bronchiolitis, inflaming and blocking combat rising use among teenagers. The group the small airways in the lungs. It appeared simi- contends that a tax increase would make the lar to “popcorn lung,” a condition observed in addictive products more unaffordable and less American microwave popcorn factory workers attractive to teenagers. exposed to the chemical diacetyl. The patient’s At Queen’s Park, NDP MPP France Gelinas breathing issues got so bad that he had to be in- introduced Bill 151, Vaping is Not for Kids Act. tubated and put on life support. He did recover, The bill aims to prohibit the promotion of vabut continued to have impairment and a chronic pour products by only allowing them to be sold safety.ophea.net injury that lasted for months. in specialty vape stores and directing tax revenue During that same month, the City of To- raised from their sale to educating the public ronto’s Board of Health called on the govern- about the health risks associated with vaping.

© Her Maje

images: health canada

1 Vaping liquid, which contains chemicals, is heated to become an aerosol

II VAPING

H E

M E C H A N I C S

aping Device (e-cigarettes, vape pens, vapes, mods, tanks, e-hookahs)

servoir liquid)

Battery

Heating element

Many shapes and sizes

Liquid (e-liquid, e-juice)

A carrier solvent

Usually propylene glycol and/or glycerol

Flavours Consists of chemicals

Nicotine (possibly) Levels can vary

liquid to vapour

h contains d to

2 The aerosol is inhaled through the mouth and lungs where it is absorbed into the bloodstream

3 The remaining aerosol is exhaled

esty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Cat.: H14-288/2018E-PDF | ISBN: 978-0-660-28651-8 | Pub.: 180588

Take a closer look: Canada.ca/Vaping

As a Private Member’s Bill (not introduced by a government Minister), the chances of the bill proceeding through to passage are low. But in February of this year, Ontario’s Health Minister, Christine Elliott, announced further actions to protect children and youth from the health risks of vaping. The plan includes • increasing access to services through Telehealth Ontario to help young people quit vaping • restricting the retail sale of flavoured vapour products to specialty vape stores and cannabis retail stores • restricting the retail sale of high nicotine products to specialty vape stores • working with online retailers of vapour products to ensure compliance with age-based sales and restrictions for online sales • requiring specialty vape stores to ensure

Two posters on vaping from Health Canada. Poster 1: Talking with your teen about vaping, a tip sheet for parents. The poster lists the reasons why vaping is not harmless as well as explains the risk of nicotine to youths. Poster 2: Vaping, The poster shows the 23 the permechanics. cent of students in grades 7–12 have tried an electronic cigarette. breakdown on the components of a vaping device as well that vapour product displays and promothat we don’t yet understand and that are Vaping devices also be used for other substances like cannabis. as a graphic explanation for howcan it works.

fa c t s .

tions are not visible from outside their probably not safe.” Vaping devices come in a variety of shapes and sizes; some resemble a stores USB flash drive. Electronic cigarettes are just as • enhancing mental health and addiction Liquids can have high levels of nicotine and come in a variety addictive as traditional ones services and resources to include vaping of flavours. and nicotine addiction and Both e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes conVaping may not leave a lingering ortain identifiable smell. • establishing a youth advisory committee to nicotine, which can be as addictive as Add-ons like vinyl skins or wraps can make items harder to users recognize. provide advice on vaping. heroin andthese cocaine. E-cigarette get The province also wants the federal governeven more nicotine than they would from a Vaping products have many names such as e-cigarettes, vape pens, vapes, mods, tanks and e-hookahs. ment to implement a national tax on vaping tobacco product. Extra-strength cartridges products. Vaping can increase your exposurehave a higher chemicals. concentration of nicotine and to harmful an e-cigarette’s voltage can be increased to get The long-term consequences of vaping are unknown. What’s important for students and a greater hit of the substance. Vaping nicotine can alter teen brain development. their parents to know? Electronic cigarettes aren’t the best Source: Health Canada. smoking cessation tool Vaping is less harmful than smoking, but it’s still not safe Although they’ve been marketed as an aid There has been an outbreak of lung injuries and deaths associated with vaping. As of February 2020, Health Canada reported 18 cases of vaping-associated lung illness. The patients presented with respiratory, gastrointestinal and other symptoms. In the United States, the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention reported 68 deaths and almost 2,800 hospitalizations from vaping. Research suggests vaping is bad for your heart and lungs

to help quit smoking, e-cigarettes have not received approval as smoking cessation devices. A recent study found that most people who intended to use e-cigarettes to kick the nicotine habit ended up continuing to smoke both traditional and e-cigarettes. A new generation is getting hooked on nicotine There are many reasons why teens are increasingly attracted to vaping products: marketing programs aimed toward youth, candy-flavoured products, ease of purchase, the belief that vaping is less harmful than smoking, lower cost and no smell, which tends to reduce the stigma of smoking. Vaping is a serious health issue that we don’t know enough about. Until we do, it is incumbent upon us to educate our young people about its side effects, consequences and dangers.

Nicotine is the primary agent in both tobacco and e-cigarettes, and it is highly addictive. It causes cravings and withdrawal symptoms. It is also a toxic substance, raising your blood pressure and spiking your adrenaline, which increases your heart rate and the likelihood of having a heart attack. According to Dr. Michael Blaha at Johns Hopkins, there are many unknowns about psweeney@principals.ca vaping, including what chemicals make REFERENCES up the vapour and howWhat they affect physi- can schools do. Canada cal health over the long term. “People need • • Health Johns Hopkins Medicine this article with your to understand thatShare e-cigarettes are poten• school Toronto Star tially dangerous to community. your health,” says Blaha. • CAMH • Ministry of Education

Organize a presentation/parent infoCancer Council “Emerging data suggests links to chronic • Australian night . and associations • School of Public Health, University of Waterloo lung disease and asthma, • Vapetrotter.com between dual use of e-cigarettes andinsmok Put posters up your school. • Centreonaddiction.org • Vox.com ing with cardiovascular disease. You’re exAsk someone from the local board of • CBC.ca posing yourself tohealth all kinds of chemicals to come in as a guest speaker. btain information materials from local O board of health or Health Canada.

The Register 13

Fur

designing schools of

the

future.

ut

e

Unlocking student wisdom

By Dr. Bonnie Schmidt, CM, FRSC

Illustration by Adrian Forrow

The Register 15

Given a blank slate and unlimited resources, Canadian youth were asked how they would design a school learning environment on Mars. We collected 10 insights into how they would re-shape their education.

With growing awareness about the challenges and pressures faced by schools to ensure students graduate prepared to thrive in an increasingly complex world, the time was right for a collaborative and respectful national discussion about the future of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) education. What began as an idea for a national education conference with senior leaders morphed into a robust consultation that included five youth summits; a series of millennial roundtable discussions; and a national conference with federal, provincial and territorial deputy ministers and education, industry and community leaders. Led by Let’s Talk Science and partners as part of Canada’s 150th birthday celebrations, this national initiative called Canada 2067 set out to determine whether diverse stakeholders share a common view of what is needed in Canada to evolve and shape the future of STEM education for students in Kindergarten to Grade 12. This in-person consultation process, online polling that garnered over 500,000 inputs and research into international education policy initiatives influenced the development of what is now the Canada 2067 vision and Canada 2067 Learning Roadmap. Some of the most valuable insight came from the 1,000 Grade 9 and 10 students who participated in a thought-provoking conversation about how they would re-build the Canadian education system – on Mars. 1

STUDENT CONSULTATION The full-day student summit events were designed to ignite their interest in STEM and seek their input around the six pillars identified through global education policy research: • how we teach • how we learn • what we learn • who’s involved • where education leads and • equity and inclusivity. Between October 2017 and April 2018, we hosted five Canada 2067 youth summits in partnership with school districts in Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, Montreal and St. John’s. Students were chosen based on their interest in participating in the consultation; many said they were not particularly interested in pursuing STEM themselves. Each summit opened with a diverse series of short and inspiring “STEM

FOOTNOTE 1 Canada 2067 was led by Let’s Talk Science with key partners including Dr. Andrew Parkin (then Mowat Centre) who led the policy research; Groundswell Projects and the Institute without Boundaries (George Brown College) designed the youth summits; Global Shapers hosted millennial roundtable discussions; Hill + Knowlton Canada designed the Canada 2067 hub and implemented the online polling; the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada and the Canadian Teachers’ Federation informed and participated in the national leadership conference. The Canadian Space Agency ensured the participation of an astronaut or senior space official at every event. National funders included the Government of Canada, Trottier Family Foundation, 3M Canada and Amgen Canada.

The Register 17

Talks,” including space-related careers. Afterwards, students worked for several hours in small pre-assigned groups, each charged with exploring one of the identified pillars with a volunteer facilitator. Collectively, teams were asked to design the first school system on Mars. They inspired us to document their contributions, including many novel project ideas, in a short book available for free download. There were distinct regional perspectives, but, interestingly, 10 insights surfaced prominently at every youth summit. THE 10 KEY STUDENT INSIGHTS h ow we teach

1. Personalization & customization: The future of STEM education doesn’t look the same for everyone. Students want richer engagements with their teachers, including more one-on-one time that could help them understand their learning strengths and create custom learning experiences. They are having trouble feeling motivated by the curriculum and wish their personal interests and passions could be tapped into more often at school. Evaluations would start with capturing student goals, their effort and progress, as well as curriculum mastery. h ow we lear n

2. Collaborative participation: Students want to be active agents in their education. Overall, they are enthusiastic about the opportunity for the school to be a learning environment for everyone, including their teachers and administrators. Students envisioned being more involved in setting learning goals and tracking progress in more diverse ways. They would include more extracurricular opportunities, as well as independent work and and teamwork as part of the evaluation process. 18 Summer 2020

3. Technology everywhere: The future of STEM education embraces technology. Students feel schools are being left behind when it comes to technology, and they don’t understand why they often have to use the same technologies their parents used in school, instead of using their smartphones. Their dream is for the latest technologies to be accessible to all students and used to enhance their learning. Students also referenced using technology differently to improve evaluation processes. w h at w e l e a r n

4. Changing the arc of education: Students think STEM learning could

change the entire approach and start in the early years to develop foundational skills and language. By middle school, they’d shift to STEM for self-development and exploring their interests. High school would include more access to experts in the community, regular exposure to possible pathways and more opportunities for job experiences like co-ops. Currently, they are not motivated by the extent of theoretical instruction they receive. 5. Experiential learning: Students would be motivated to learn and develop competencies by connecting STEM concepts to real-life prob-

Students want richer engagements with their teachers, including more one-on-one time that could help them understand their learning strengths and create custom learning experiences.

lems in a hands-on way. There were strong calls to collapse the disciplines, integrate STEM with humanities and arts, and use real problems to deepen their understanding of foundational theories through application. They seek more opportunities to engage in learning outside the classroom with real-world practitioners working on solutions to challenges. Evaluations would shift to include effort, behaviour and improvement. In turn, marks would lose their current stronghold in defining student identity.

The Register 19

problems in a hands-on way. There were strong calls to collapse the disciplines, integrate STEM with humanities and arts, and use real problems to deepen their understanding of foundational theories through application. They seek more opportunities to engage in learning outside the classroom with real-world practitioners working on solutions to challenges. Evaluations would shift to include effort, behaviour and improvement. In turn, marks would

lose their current stronghold in defining student identity. who’s involved

6. Mentorship: Students crave relationships with caring and trustworthy adults and consistent exposure to experts outside of school. They want help with navigating school, including understanding the fundamental act of learning how to learn and interact with teachers. They want help in learning

[Students] seek more opportunities to engage in learning outside the classroom with real-world practitioners working on solutions to challenges.

20 Summer 2020

to cope with stress and bullies as well as how to stay motivated. They seek advice about pathways and support building healthy lives. where education leads

7. Critical thinking and problem solving: To be resilient and flexible, students need to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Students are aware that they need to become experts at deconstructing ideas and developing their own informed points of view. They stressed the value of practicing skills using relevant contexts and the importance of formalizing post-project

A photo of students participating in a youth summit to reimagine the Canadian education system on Mars, as part of the Canada 2067 national initiative. Photo from Let’s Talk Science.

reflections. They are looking for more opportunities to practice sharing their ideas in diverse ways – by speaking, writing, making and prototyping. 8. Self-awareness and direction: STEM education will help students develop self-awareness to build on strengths, improve limitations and move in new directions. They want to connect academic skills, character traits, passions, behaviours, values and aptitudes to the job market. equity AND inclusivity

9. Well-being: Students envision a culture that supports feeling good in your own skin and developing the skills to help others feel good in theirs. They are feeling the weight of stress. They want a school system where the happiness of students, teachers and administrators is paramount. They want to be in a place that is supportive and inspiring, where diversity and inclusion are practiced. Their vision for healthier schools includes healthy and affordable food, frequent breaks for movement and rest and flexible schedules that are more in harmony with the circadian rhythm of teens. 10. Space and comfort: Students want safe, clean, bright and inspiring spaces with more natural light, large flexible spaces that support diverse uses and different types of areas, including labs, maker-spaces, kitchens and libraries. There would be spaces designed to connect socially, places to work in solitude and in collaboration. In addition to cutting-edge technology, students want environmentally responsive and sustainable buildings.

HOW THE CANADA 2067 INITIATIVE IS INFLUENCING CANADIAN EDUCATION While the students imagined learning on Mars, in several provinces across Canada there are new initiatives underway that align with or are also reflective of the Canada 2067 recommendations. Ontario The Halton District School Board (HDSB) has used the Canada 2067 Learning Roadmap as a guiding framework for the development of its new I-STEM program. The areas of focus (e.g., How we learn, What we learn, etc.) anchor the work of the I-STEM Advisory Team, which is composed of diverse stakeholders (staff, parents, post-secondary, industry, community). They are referencing the guiding recommendations as the team builds and reflects on the learning for students and further program development. The 10 key youth insights, coupled with HDSB’s Student Focus Group results, provided student voice to frame the learning experiences for students. As a result, I-STEM learning is more interdisciplinary, issues-based and experiential. Students in I-STEM have opportunities that support invention and innovation to make a difference in the world. Connections with post-secondary education partners, industry and the broader community bring authentic issues-based learning opportunities to the students. The I-STEM Program Overview and Year 1–Engineer’s Toolkit reflect the vision for learning in I-STEM. Nova Scotia Let’s Talk Science, in partnership with the Government of Nova Scotia, is supporting the implementation of the new science curriculum by providing professional development for school administrators that incorporates Canada 2067 recommendations. Saskatchewan In partnership with the Government of Sas-

katchewan, broadcast technology provides job-embedded professional learning for educators and students in a co-learning environment to build skills in computational thinking and coding. BUILDING A FUTURE WITH CANADA 2067 As we look towards the bicentennial year when many of today’s teens will be considering their retirement, it’s clear that we can’t wait 50 years to improve STEM learning! With students at the centre, Canada 2067 offered a powerful platform to engage diverse stakeholders in discussing the future of STEM education. The positive participation and strong alignment across all audiences indicated an understanding that change is needed and that a collaborative approach offers a constructive path forward. Keeping students engaged as active participants in their learning and learning environment will help lead to a collaborative design for the future of education, and a guide to building the resilient problem solvers of tomorrow. Dr. Bonnie Schmidt, CM, FRSC, is the President and Founder of Let’s Talk Science. @LetsTalkScience bschmidt@letstalkscience.ca FURTHER READING

All Canada 2067 reports are hyperlinked below and available in English and French at Canada2067.ca. Additionally, videos from the youth summits and national leadership conferences are also available online. CANADA 2067 LINKS

Canada 2067 Learning Framework – overview (English / French) Canada 2067 Learning Framework – full (English / French) Research Backgrounder – overview (English / French) Research Backgrounder – full (English / French) Youth Insights Book (English / French) Youth Insights overview (English / French) Youth Summit Videos (overview /event pageEnglish / French) Global Shapers Millennial Report (English / French) National Leadership Conference (English / French)

The Register 21

REGISTER REPORT

Principal Well-being Strategies and coping mechanisms in times of uncertainty By Dr. Katina Pollock and Dr. Fei Wang

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted every facet of the public sphere, and public education has been hit especially hard. For education workers who already experience high levels of stress, the rampant uncertainty is introducing new stressors that can and likely will negatively impact their well-being. Although some things will eventually return to normal, most public sectors, including education systems, will likely not return to “business as usual.” As such, it has become even more crucial for principals to focus on their own well-being and develop strategies and healthy coping mechanisms that they will be able to rely upon for years to come.

22 Summer 2020

Until recently, well-being research and initiatives in public educa-

important. The majority of our research has been on principals’

tion focused predominantly on students and teachers. As read-

and vice-principals’ work in Ontario. In the last 10 years, we have

ers of this magazine know, principal well-being is also critically

witnessed some worrying trends in how work intensification is

negatively influencing principals’ overall well-being. As reported

FIGURE 1

OVERALL WELL-BEING

in the previous issue of The Register, principals are being increasingly exposed to violence in their work. According to the 2018 ETFO report, 84% of principals and vice-principals in the province were directly involved in an incident of student violence.

Good/Excellent

Neutral

Poor/Very poor

In 2019, we conducted a study that specifically focused on the principals’ well-being in Ontario and British Columbia. A virtual survey was sent to participating OPC principals that ad-

30%

dressed seven components of their well-being. The survey had a response rate of 36%. We used Ontario’s Well-Being Strategy for Education to help define our terms

44%

and frame the survey. For example, we used the framework’s definition of wellness — a positive sense of self, spirit and belonging that people feel when their cognitive, emotional, social and physical needs are being met — to inform and structure the survey. At the time of this publication’s release, the survey data is still being analyzed, but has been subjected to descriptive statistics. In this article, we aim to use this preliminary analysis to provide a snapshot of our findings on Ontario principals’ well-being and offer some strategies for supporting it.

25%

OVERALL WELL-BEING The survey asked principals about their overall well-being. Of those who responded, 44% indicated that they believed their well-being to be good or excellent. On the other hand,

ships with students, vice-principals, school support staff,

25% responded being neutral while 30% indicated that their

administrative assistants and teachers, while 16% indi-

well-being was poor or very poor (Figure 1).

cated this was not the case with union representatives.

We also wanted to know more about their social, cognitive, psychological, emotional, spiritual and physical well-being.

Cognitive Well-Being Fifty-four per cent of principals indicated that their cognitive

Social Well-Being

well-being at work was good or excellent, and 46% indi-

Although 62% of the principals felt that their social well-

cated their cognitive well-being was neutral, poor or very

being at work was good or excellent, 38% felt it was neutral,

poor. The majority of participants (85%) indicated that they

poor or very poor (Figure 2). Similarly, although 52% re-

were able to make decisions under high amounts of pres-

ported feeling respected at work, 42% reported feeling

sure, with 82% being able to initiate tasks.

isolated. Other feelings included supported (40%), connected (38%), accepted (36%), satisfied (28%) and wel-

Psychological Well-Being

comed (28%). There were also those who felt unsupported

While 46% of respondents indicated feeling good or excel-

(29%), distanced (27%) and dissatisfied (22%).

lent about their overall psychological well-being at work,

In terms of positive work relationships, a majority of par-

54% indicated their psychological well-being at work was neu-

ticipants often or always experience positive work relation-

tral, poor or very poor. More encouragingly, 86% indicated that The Register 23

REGISTER REPORT

they often or always feel they have developed as a principal since they began the role and 76% reported that they often or always feel confident and positive about themselves as a principal.

Good/Excellent Neutral/Poor/Very poor

Emotional Well-Being About a third (37%) of participants indicated that their emotional well-being at work was good or excellent and

FIGURE 2

63% indicated it was neutral, poor or very poor (Figure 3). When asked which adjectives described how their work

SOCIAL WELL-BEING

made them feel emotionally, 569 out of 860 respondents chose frustrated. Despite this, 44% indicated that they are often or always satisfied with their work and 69% reported to be often or always passionate about their work.

38%

62%

Spiritual Well-Being When asked about their overall spiritual well-being, 56% of the participants indicated that they were neutral, which was not unexpected given they work in the secular public school system. However, almost 40% of those who responded indicated that their spiritual practices provide them with a sense of direction and purpose at work. Physical Well-Being For physical well-being, 2% indicated it was excellent, 24%

FIGURE 3

said good and 74% indicated they had neutral, poor or very poor physical well-being.

EMOTIONAL WELL-BEING

FACTORS THAT AFFECT PRINCIPALS’ WELL-BEING

63%

Draining Situations

37%

According to the survey data, the top three things that contribute to draining situations for principals at work are • lack of special education support/resources • volume of emails and • mental health issues among students. These top three contributors were also the same when we surveyed OPC principals in 2013, OPC vice-principals in 2017 and ADFO French and French-Catholic principals in 2019. Safety Draining situations are also connected to safety issues. The 2018 ETFO survey reported that Ontario elementary teachers have experienced increased rates of violent incidents at

24 Summer 2020

REGISTER REPORT

‌ principals can still develop a regime of both personal and professional strategies to help promote their own wellness and safety on an individual level.

work. Principals work in these same schools and are not

Strategies

immune to these safety issues. Although there has been a

Although many of the issues concerning well-being require

strong emphasis on well-being and wellness in the public

changes at the system level, principals can still develop a

education sector, the notion of safety has not always been

regime of both personal and professional strategies to help

associated with or included in well-being discussions.

promote their own wellness and safety on an individual

Other than the leading research emerging from Australia

level. An overall comprehensive approach to well-being is

(Riley 2019) the voices of school principals who have ex-

essential and will likely include practices that attend to all

perienced their own safety issues are fairly absent from the

aspects of wellness.

literature. In this survey, principals reported experiencing passive-aggressive behaviours, gossip and slander, esca-

The following strategies point to the wide variety of available options for administrators.

lated conflicts and quarrels, false accusation, threats and violence and harassment. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on four of

1. Take inventory of your work stressors Most principals agree that their work involves a

these issues.

number of stressors. New work contexts, such as

1. Discrimination

the current COVID-19 pandemic, can present other

While 46% indicated they had not experienced

unintended consequences and stressors. What is

discrimination, others experienced various forms of

considered a stressor depends on several factors,

discrimination such as gender, age, race, sexual orien-

ranging from individual personal leadership resources

tation, religion or ability.

to school demographics.

2. Harassment

Building on advice from the American Psychology

Only 16% indicated that they have not been harassed

Association (APA), and in the context of uncertainty

in their principal role. For those who were, almost

regarding how public education will proceed during

three quarters indicated that they were harassed by

and after the COVID-19 pandemic, you first need to

parents(s)/guardian(s)/family member(s) and almost a

determine what your individual work stressors are and

third were harassed by a teacher or teachers.

how you react to them. How you track them is also

3. Physical assault

very individual. The key is to not merely identify your

Over one-third indicated that they had been physically

work stressors, but also to determine what your reac-

assaulted, while 36% indicated that they were not.

tions are.

Most of the assaults were from students. 4. Threats

.

As you name and document your stressors and reactions over time, patterns emerge in terms of what

Only 14% indicated that they have never been

and where particular kinds of events and activities

threatened. The top two groups of aggressors were

can trigger particular kinds of thoughts and emotions,

parents(s)/guardian(s)/family member(s) and students.

which in turn elicit specific reactions. Naming these The Register 25

REGISTER REPORT

Establishing a physical activity routine during extreme times of change can increase the probability that the positive habit will continue when a new normal is established.

Establishing a physical activity routine during extreme times of change can increase the probability that the positive habit will continue when a new normal is established. Many magazines have created lists of the best and most highly rated fitness and nutrition apps, which are a good place to start looking for one that might work for you. 4. Maintain good sleep hygiene Years of research have demonstrated that sleep and stress are mutually informing: stress can disrupt sleep and lack of sleep or sleep loss can increase stress levels (Vgontzas et al. 1998; Vgontzas and Chrousos 2002). Sleep loss can negatively influence cognitive, physical and emotional

stressors and patterns are a crucial foundation for

well-being. Having good sleep habits is often referred to

making informed decisions and actions about your

as good sleep hygiene. There are several great resources

well-being. We suggest that stress inventory be a

available for free that principals can take advantage of, such

continual exercise that is revisited periodically as your

as those created by the National Sleep Foundation. Some

work environment changes, rather than a one-off.

of the strategies include creating and sticking to a sleep schedule, evaluating where you sleep in terms of tempera-

2. Develop healthy responses We all respond to stress, but the key is to strive for

ture, use of light, mattress and pillows and avoiding other things that can disrupt sleep like alcohol and smoking.

healthy responses. In our study, we asked principals how they cope with a draining day at work. The top five

5. Manage your use of email

responses were spending time with family/friends/pets,

One of the most prevalent issues that principals deal with

watching TV/movies, talking with family/friends, physi-

is the overload of emails. In this study, principals reported

cal activity/exercising and talking with colleagues.

spending 10.5 hours per week on emails. Managing

The manner in which a strategy is used is equally if not

email is not as simple as merely ignoring them or hoping

more important than the strategy itself. For example, eat-

this mode of communication will eventually go away; nor

ing and sleeping could potentially be both beneficial and

is trying to simply handle them faster an efficient way to

destructive. Eating well and sleeping eight hours a night

deal with email overload. How to manage your emails is a

could contribute to a person’s well-being, but over– or

very individual endeavour, making it difficult to implement

undereating and over– or under sleeping could result in

universal support across an entire school system. We

or exacerbate physical and mental health problems.

suggest strategies such as setting boundaries around email use, reading them once and using email folders.

3. Find a new physical activity routine. In our past qualitative research, principals often

CONCLUSION

indicated that they intend to be more physically fit and

26 Summer 2020

physically healthier. Many did have gym memberships

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a great sense of

and personal trainers but they did not take advantage

uncertainty. The pandemic and its impact on public educa-

of them because they did not have the time or were too

tion will likely continue to perpetuate principals’ work inten-

exhausted. While recent physical distancing restric-

sification. This is a critical time – principals must not only

tions have made it impossible to attend the gym, it has

support their students and staff, but also take their own

also uncovered creative ways for individuals to maintain

health and well-being seriously. Amidst all of the uncer-

good physical health and demonstrated that physical

tainty, this can be an opportunity for school leaders to assess

fitness can be a part of a person’s life without having to

their wellness and create positive habits that will promote

enrol in formal programs at a separate location.

well-being for the rest of their careers.

REGISTER REPORT

A copy of the full well-being study report will be posted here in late spring 2020. Dr. Katina Pollock is an associate professor at the Faculty of Education at the University of Western Ontario. Her research focuses on school leaders’ work intensification and well-being, policy development and implementation, and knowledge mobilization. @DrKatinaPollock katina.pollock@uwo.ca

Dr. Fei Wang is an associate professor at the Faculty of Education at the University of British Columbia. His research interests include educational leadership and administration, social justice and diversity, educational organization and policy studies, and international and comparative education. @DrFeiWang Fei.wang@ubc.ca

FURTHER READING

Easing the Stress at Pressure-Cooker Schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(3), 15–19. Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, Period, and Cohort Trends in Mood Disorder Indicators and Suicide-Related Outcomes in a Nationally Representative Dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(3), 185–199. Wicher, M. (2017). Positive Psychology: A pathway to principal wellbeing and resilience. Education Today, 17(1), 24–26.

Carter, S. (2018). The Journey of a Novice Principal: Her struggle to maintain subjective wellbeing and be a spiritual school leader. International Journal of Education, 10(3), 119–142. Riley, P. (2012). The Australian Principal Health and Wellbeing Survey. Victoria, Australia: Faculty of Education and Arts Villeneuve, J. C., Conner, J. O., Selby, S., & Pope, D. C. (2019).

Why is it important for students to volunteer? a. Helps to build leadership skills. b. Increases confidence and clear communication. c. Leads to better grades. d. Earns volunteer hours for graduation. e. All of the above.

Help students build key skills to become leaders of tomorrow. Learn more about hosting a Youth Teaching Adults https://youthteachingadults.ca/ workshop at YouthTeachingAdults.ca This project has been partly funded by the Government of Canada through the Digital Literacy Exchange Program.

The Register 27

Year in Review.

Moving forward after significant challenges By Protective Services Team

28 Summer 2020

Illustration by Anthony Tremmaglia

TA and article, OEC is th g tin ri w f the OSSTF At the time o agreements. e tiv ta n te ached overnment. ETFO had re ns with the g tio tia ith o eg n in pandemic w was still d due to the se o cl e er w Schools . date for return no confirmed

The 2019–20 school year has been heavily impacted by labour action. As a result, this has not been a typical year in Ontario, as labour action has meant that it is not “business as usual” in our schools. EQAO assessments have been cancelled, strikes have caused schools to be closed to students, extracurriculars have been impacted and administrators have been unable to work on school improvement planning with their staff. And then in March, these challenges were further heightened by the global pandemic in our communities and across the world.

30 Summer 2020

It has been a taxing year, as principals and vice-principals have worked hard to maintain safe environments for students while the escalating job action has disrupted the school environment. This is part of labour relations; the push and pull of negotiations includes the strategy of employing job sanctions. But because of the legacy of a strong education system already in place before this year started, we have been able to deal with the challenges in part by relying on the strong relationships nurtured over many years. This year in particular, school administrators have demonstrated their collective ability to separate their staff relationships from the issues at hand. It is important that you continue to value your staff and recognize that labour action is part of working in a unionized environment. Once new collective agreements are ratified, principals and viceprincipals will need to familiarize themselves with each employee group’s agreement and the implications of these various agreements at the school level. Each district OPC will need to advocate for school board training sessions that provide guidance regarding how to do that. As provincial bargaining winds down, it is important to remember that the process has been exhausting for all parties. Union members have been obligated to follow the job sanctions prescribed by their union. The rising tension of following these directives, the anxiety of waiting for a resolution, the loss of wages and dealing with the public have all taken a toll on our staff members. It is difficult for them to stop doing work that they normally do. At the same time, principals and vice-principals have taken on work that we typically are not required to do. We have also had to deal with the reactions of students, parents and the public to labour disruption while continuing to support our school community. All of this leads to complexity and can affect professional relationships within a school. To rebuild relationships with our staff, principals and vice-principals will need to consider the dynamics on our own team. Are there individuals who feel disillusioned with the process of labour action? Have some individuals alienated themselves from others? Are some team members showing signs of mental or physical strain? It is important for school leaders to recognize that at the end of job action, everyone

districts Tips for local rson or nior staff, in pe se ur yo ith w t mee the work of prin • Continue to es that impact su is s us sc di virtually, to ur unrest ends. rincipals as labo -p ce vi d an ls cipa bers regarding sources for Mem re g/ in in tra r fo ck to the • Advocate d provide feedba an ts en em re ces needed. the collective ag of training/resour pe ty e th t ou ab f ce-principal senior staf cipal and/or vi in pr ng vi ha ds e board/school • Work towar ittees that includ m m co on n tio s of having representa staff the benefit or ni se ith w re operations. Sha ho report back e committees w es th on s er ad school le rict. to the local dist rs to understand to local Membe t ou h ac re to • Continue level. e at the school rt issues that aris T District Suppo ate with your PS ic un m m co to • Continue Consultant.

may not be able to “let go” of the situation and return to the pre-labour climate easily. Taking the time to restore individual relationships, as well as the dynamic of the entire school team, will be important. In your role as school leader, consider how to help people repair these differences. At the time of writing this article, the COVID-19 virus is spreading throughout our communities and social distancing is very much the new norm. Typically, we would encourage you to initiate face-to-face contact with your staff. However, there are ways to connect virtually as well. Consider connecting through email, text messages and social media. Perhaps a group chatroom could be set up so that people are able to connect as a group and see how everyone is doing. Using a virtual platform such as Google Hangouts, FaceTime, Microsoft Teams and Zoom is another way to enhance communication within groups and help dispel that sense of isolation that many are feeling during this time of uncertainty. Depending on the dynamics within your own school, it may be necessary to re-establish your relationship with your school’s union representative(s) and develop plans to implement the elements of the new collective agreements. Moving forward, you need to continue to consult and work with these representatives, to help rebuild the collaborative climate in the school and facilitate new initiatives. In terms of community relationships, there is no doubt that families have been impacted by labour action. During this last round of negotiations, public opinion seemed to be quite supportive of the employee groups. However, others may not have been, and it will be important to help re-establish relationships our school community.

Tips for prin cipals and vice-pri ncipals in s chools • Read the n ew collective agreements cation from and ask for c your Superv larifiisory Officer Resources re a n d /o r garding imple Human mentation of that arise. specific issue s • Meet with the union rep resentatives re-establish g in your scho ood commun ol to ication, positiv and a sched e relationship ule of regular s check-ins. • Connect w ith your staff and draw ou share as a team t the things . Encourage e you veryone to wo of mutual re rk in a climate spect as yo u work toge student outc ther to impro omes. ve • Reach out to parents a nd communic help allay the ate with them ir concerns re to garding the lo time and the st instruction ir child’s prog al ress. • Contact yo ur School C ouncil Chair practicality of and discuss and plans for the moving forwar initiatives and d on any futu projects. re • Share any concerns with your local OP • Monitor yo C reps. ur own health an d seek profess your Employe ional help from e Assistanc e Program a Minds as nee nd/or Starlin ded. g

The Register 31

Think about ways to communicate positive messages to your school community about the work you, your staff and your students are doing. Look for ways to re-engage the parents and focus the comS O A )within your school. munity on how best theP students O N (O S O C IAtoTIsupport S A R E IC F F O Y During negotiations, we have monitored our districts and their C S U P E R V IS O R O N TA R IO P U B LI progress using our own check-in model by using Zoom meetings to COMMENT gather feedback about local issues and to help problem-solve the We ic.meetings ndem concerns that were presented. The feedback from these has D-19 pa ything like the COVI an h ug ro th e es th of been very positive, and it has established a at weekly between bothconnection iting of this effect th conceptualized the wr underestimate the ot nn ca we r When we (OPSOA) ou om lab wh our district support consultants and the local representatives. As we e with next after have had on all thos s on “what happens s wa ge s en cu fo all e ch ed th ct le, pe tic ex from across ar grappled with issues, it was importantca fornnlocal leaders ot be d our school the pandemic hit an ne has a story. We rk. Evertoyohear wo ch issues e ea unrest is over?” Then g at rin ip du the province how other districts were handling various antic rned story, each result or cantly. The lessons lea ch nifi ea sig ow d kn ge to an ch de ar ye be un r-locally for and such as EQAO and report we cards, ent,advocating presare be they ver,and th the labour unrest ho bo n, m ca fro e ge W en n. all tio ch ac re colleagues. ays this time of their us well as we help. We have alw d ask how we can pandemic will serve an 19 Dng VI di an CO st e we th m re fro It was gratifying to see solutions e to ensulocally by one timdeveloped hool and it iswere d;that e better together. Sc care of those we lea n ke vta regithrough move forward. We ar r the ca ve ofhelp board being shared and used in other boards work care to er like ne each other – to take rs have come togeth of to re tra ca nis mi ke ta ad ay m m ste o sy whstrong sense of the situation in their ownec area. We appreciated that meet a colleaguethe lutions to problems time to ch k in on Take s. er ol finishing before to develop so ho be sc al ay partnership that emerged from these discussions and believe that this ividu who m ll as needs at the ind administrator, one we e as gl s, sin ed a ne be c mi en ste ev sy es, orand their senior between local OPC groups in tim continue if we two-way communication certa e un nversation needs to career during thes their level. This type of co teams needs to continue. Although these weekly meetings were r as a school system. ! ge ss on str bo e ow th gr to e k ar d the action, the spea intended to provide additional support tion anlabour r situaduring out opportunities to the labou ht th ug bo so e, ely m tiv so r ac Fo ve ents. ConWe ha atic ev districts andenPST District Support traum we have to collaboration between local are the best of what pandemic have be sh 19 to , Dice VI O vo C e on vention th er st wi int membership out our The tru sultants will continue to benefit ourou organization t there aband rning lea d from one another. st an th be e wi th rn ss lea ce to d Ac offer an ed to dealing with als to ask for going forward. has allowed individu ntion strategies relat ilt ve st bu po en d be an s ha weour local at th s asand sionally To strengthen the relationship between senior ce teams be invaluable resour to politely and profes ll d wi an ey nd Th ha a. a r um fe of tra help, to rmal.of respect and groups, it is important to acknowledge that thenospirit r new ge the status quo. ard, returning to ou rw fo e ov m ys disagree and challen thist alo challenging time needs to become act in wa cooperation that existed during ne. use some people to member, you are no Re Labour unrest may ca en the new norm. What we experienced is characterized by Leithwood ver be seen. And we’ve ne that we have never (2012; 2013) as “productive working relationships” (Ontario Leadership Framework). Valley DSB. We know that as we move forward, we are going to continue , is with the Thames A SO OP of t en to grapple with complex issues that require the same type of collective rrent Presid Karen Edgar, the cu problem solving. If classes resume before the school year closes, it is important to recognize that we cannot make up for all of the disruption to the school year in a shortened period of time, such as the school improvement planning process which has been impacted by both labour action and pandemic isolation. Rather, staff should spend their time reconnecting with students and restoring relationships with an aim to finishing the school year as positively as possible. As the school year comes to a close, it is important to reflect on our own personal well-being and how we have managed the stress of

32 Summer 2020

Sidebar: Tips for local districts.

Ontario public supervisory officer association (OPSOA) comment.

• Continue to meet with your senior staff, in person or virtually, to discuss issues that impact the work of principals and vice-principals as labour unrest ends. • Advocate for training/resources for Members regarding the collective agreements and provide feedback to the senior staff about the type of training/resources needed. Taking the time to restrepresentation • Work towards having principal and/or vice-principal ore on committeesin that board/school operations. Share with diinclude vidual relationships, senior staff the benefits of having school leaders on these committees who report tolthe asback wel aslocal thdistrict. e dynamic of the • Continue to reach out to local Members to understand issues that en arise at the schooltilevel. re school team, w ill be • Continue to communicate with your PST District Support Consulimportant. tant.

When we (OPSOA) conceptualized the writing of this article, the focus was on “what happens next after labour unrest is over?” Think about ways to communicate positive messages to your school Then the pandemic hit and our school year changed significantly. community about the work you, your staff and your students are The lessons learned during this time of challenge from both the doing. Look for ways to re-engage the parents and focus the comlabour unrest and from the COVID-19 pandemic will serve us well munity on how best to support the students within your school. as we move forward. We are better together. School and system During negotiations, we have monitored our districts and their administrators have come together like never before to develop progress using our own check-in model by using Zoom meetings to solutions to problems that meet systemic needs, as well as needs gather feedback about local issues and to help problem-solve the at the individual school level. This type of conversation needs to concerns that were presented. The feedback from these meetings has continue if we are to grow stronger as a school system. been very positive, and it has established a weekly connection between We have actively sought out opportunities to speak with one Sidebar: Tips for principals our district support consultants and the local representatives. As we voice, to share the best of what we have to offer and to learn and vice-principals in schools. grappled with issues, it was important for local leaders from across with and from one another. The trust that has been built has the province to hear how other districts were handling various issues • Read the new collective agreements and ask for clarification from allowed individuals to ask for help, to offer a hand and to such as EQAO and report cards, and they are advocating locally for your Supervisory Officer and/or Human Resources regarding politely and professionally disagree and challenge the status their colleagues. roles during theofpast year. issues It has been a lonely time for many, as implementation specific that arise. quo. It was gratifying to see solutions that were developed locally by one labour action halted the collaborative team activities that many of Labour unrest may cause some people to act in ways that we • Meet with the union representatives in your school to re-establish board being shared and used in other boards to help work through you find so rewarding. Taking stock of our own and personal health and good communication, positive relationships a schedule of have never seen. And we’ve never been through anything like the situation in their own area. We appreciated the strong sense of finding the time to use the resources we need to stay healthy is regular check-ins. the COVID-19 pandemic. We cannot underestimate the partnership that emerged from these discussions and believe that this important as we head into the summer months. • Connect with your staff and draw out the things you share as a effect that both of these challenges have had on all those two-way communication between local OPC groups and their senior As we reflect oneveryone the 2019–20 school let’s shift the conversateam. Encourage to work in ayear, climate of mutual respect with whom we work. Everyone has a story. We cannot be teams needs to continue. Although these weekly meetings were tion from the differences that may have separated us to the similarias you work together to improve student outcomes. expected to know each story, each result or anticipate each intended to provide additional support during labour action, the ties thatout we share. Revisitand our communicate common goal ofwith helping students • Reach to parents them to helprealize allay reaction. We can, however, be present, be understanding collaboration between local districts and PST District Support Contheir potential, both academically and with respect to their well-being. their concerns regarding the lost instructional time and their child’s and ask how we can help. We have always taken care of sultants will continue to benefit our organization and our membership With the year that has been, it is even more imperative that we work progress. those we lead; it is time to ensure we take care of each other going forward. together your to help stabilize and support ourdiscuss student the communities. • Contact School Council Chair and practicality of – to take care of the caregivers. Take time to check in on a To strengthen the relationship between senior teams and our local and plans for moving forward on any future initiatives and projects. colleague who may be a single administrator, one who may asayed@principals.ca groups, it is important to acknowledge that the spirit of respect and • Share any concerns with your local OPC reps. be finishing their career during these uncertain times, or even cooperation that existed during this challenging time needs to become RESOURCES TO TRAUMA/TRAUMATIC EVENTS • Monitor yourRELATED own health and seek professional help from your the boss! • School Mental Health Ontario the new norm. What we experienced is characterized by Leithwood Employee Assistance Program and/or Starling Minds as needed. For some, both the labour situation and the COVID-19 • North American Center for Threat Assessment and Trauma Response (2012; 2013) as “productive working relationships” (Ontario Leadership • Ontario Principals’ Council pandemic have been traumatic events. Access the best Framework). We know that as we move forward, we are going to continue learning out there about intervention and postvention to grapple with complex issues that require the strategies related to dealing with trauma. They will be same type of collective problem solving. invaluable resources as we move forward, returning to our If classes resume before the school year closes, new normal. it is important to recognize that we cannot make Remember, you are not alone. up for all of the disruption to the school year in Edgar, period the current President OPSOA , is with the Thames Valley aKaren shortened of time, suchof as the school DSB. improvement planning process which has been impacted by both labour action and pandemic isolation. Rather, staff should spend their time reconnecting with students and restoring relationships with an aim to finishing the school APPLY BY NOVEMBER 15, 2020 year as positively as possible. jointphdined.org As the school year comes to a close, it is important to reflect on our own personal wellbeing and how we have managed the stress of

CANFAR.COM/ORDER

The Register 33

Seeking Reconciliation Champions

Framework for reconciliation in Ontario schools By Minou Morley Illustration by Don ChrĂŠtien

we are conscious of the fact that many of our high needs students self-identify as Indigenous, and we are working to ensure that these students get the attention and support they need and deserve. The Assembly of First Nations and the Government of Canada both assert that Indigenous youth are more likely to live in poverty and die by suicide than are their non-Indigenous peers, and much less likely to graduate from secondary or postsecondary schools.

The Register 35