The following article was written by an Iranian citizen journalist on the ground inside the country, who writes under a pseudonym to protect his identity.

For Iranian athletes, the most serious red line to cross is competing against Israeli athletes or an Israeli sports team. Any Iranian athlete who dares ignore this ban can expect harsh retributions.

But this week, Iranian footballers Masoud Shojaei and Ehsan Hajsafi defied the ban, playing for Greek team Panionios against the Israeli team Maccabi in a third qualifying round match for the Europa League.

The footballers, both of whom are members and captains of Iran’s National Football Team, played in the first qualifying game for the Europa League championship against Slovenian team Gorica. Panionios won the match and went on to face the Maccabi Tel Aviv football team in the second round, playing in Israel on July 27. It was the usual scenario: The two Iranian athletes used the “injury” excuse to avoid playing Israeli athletes. Three days before the match, the club’s website announced that its two Iranian players would not be participating in the match due to injuries. Panionios lost to Maccabi 0-1, an outcome that arguably could have been different if the team’s two Iranian players had been on the pitch.

Then it was time for the return match. Panionios issued a statement on its website saying that the team needed the two Iranian players in its next match against Maccabi — and that it was an issue of honoring their contracts with the club. “Panionios club,” said the statement, “respected the decision by Shojaei and Hajsafi not to accompany the team to the occupied territories, [but now] it wants these two footballers to respect their contracts and compete in the return visit so that the team can advance to the next round. Professional athletes...must respect their contracts.”

On August 3, Masoud Shojaei and Ehsan Hajsafi who could no longer use “injury” as an excuse, went on to the field to play Maccabi Tel Aviv. Panionios lost again, 0-2, but history had been made: After 33 years, Iranian athletes had officially competed against Israelis. The news spread fast.

Islamic Republic officials lost no time in denouncing the two athletes. The Ministry of Sports issued a statement that said: “After receiving necessary information and reports from the Football Federation and other sources, the Sports Ministry will make appropriate decisions within the framework of the principles of [Iran’s] foreign policy and of safeguarding the national interest.”

In its own statement, Iran’s Football Federation strongly condemned the two members of its National Football Team. It too promised to reach a decision after a thorough review and a “face-to-face talk with these two players.”

The Israeli Foreign Ministry posted a tweet in Persian praising the two Iranian footballers for breaking the taboo and defying the ban on competing with Israeli athletes. Many Iranian football fans did the same, although there were plenty of Iranians on social media that sided with the ban and condemned the players too.

A Decades-Long Ban

The ban on competing with Israeli athletes was imposed after the victory of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Before that, Iran and Israel had competed against each other on sports fields numerous times. The match best remembered by Iranians — including Iranian politicians — was the Asian Cup final of May 19, 1968, which took place at the 30,000-seat Amjadieh Stadium (now Shahid Shiroudi) in Tehran. That day, Homayoon Behzadi and Parviz Ghelichkhani scored goals, winning Iran the Asian championship. The victory was made all the more historic because it was the first time that Iran had competed in the championship.

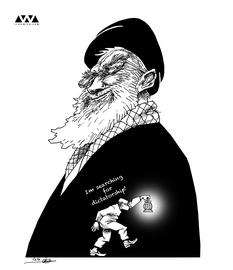

After the 1968 victory, Iran erupted in celebrations. Ayatollah Khamenei, now the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, called the demonstrations of jubilation an instance of “fighting Israel.” In 1983, he remembered the match in an interview [Persian Link]:

“In those days, I was a young seminary student. The general mood in Tehran was against the Israeli team. After the game all the people of Tehran showed their joy for this victory. The taxi driver said ‘Did you see how we scored?’ This showed that the Iranian people were unhappy about the shah’s cooperation with Israel.”

Everything changed after the revolution, but not immediately. In 1983, the FILA World Wrestling Championships were held in Kiev, which was part of the Soviet Union in those days. Iranian and Israeli wrestlers came face to face. Iranian Greco-Roman wrestler Bijan Seifkhani went to the mat against Robinson Konashvili from Israel in the 74-kilo category and won 7 to 4. The ultra-conservative newspaper Kayhan and its sports supplement published articles celebrating the success and praising Seifkhani as a great champion because he had defeated an Israeli athlete. Kayhan’s editors seemed unaware that this would mark the end of an era, and that no longer would Iranian athletes be able to compete against Israeli athletes.

Immediately after the news of Seifkhani’s victory, the then-Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati ordered the Iranian team to return to Iran immediately. Iranian wrestlers received the order late at night. The coaches went room to room, woke up the wrestlers one by one and told them to pack because they had to return to Tehran. And when they arrived back, every member of team, athletes and non-athletes alike — but especially Seifzadeh — were severely reprimanded.

Then the Iranian government made a categorical announcement: No Iranian athlete was to compete against “Zionists” under any condition, whether in official competitions or in an unofficial capacity.

Defending The Palestinian People

For more than two decades, Iranian media used the same sentence over and over again to explain the ban: Iranian athletes do not compete against Israeli athletes out of support for the rights of the Palestinian people.

But what is interesting here is that, during all those years, Palestinian and Israeli athletes have regularly competed against one another in a large number of sports. For example, although Palestinians have persistently tried to oust Israel from FIFA, when the Palestinian Football Team participated in the Asian Cup Games for the first time in 2015, five of its footballers were Israeli Arabs. After this news emerged, it took the Iranian Intelligence Ministry less than 12 hours to ban domestic media from reporting on it in any way.

Over the last two decades, numerous Iranian athletes have ruined or damaged their careers because they have refused to compete against Israeli athletes — bowing to a set of rules enforced on them by the Islamic Republic. The last Iranian athlete to refuse to compete against his Israeli opponent was the judo athlete Arash Mir-Esmaili. At the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, he was considered the greatest chance for Iran to win a medal; at the opening ceremonies it was he who carried the Iranian flag. In the first lottery, Mir-Esmaili was matched against Ehud Vaks from Israel. All too aware of the ban on competing against Israelis, he disqualified himself by claiming he was overweight. Iranian media, however, had no qualms about telling the truth. A spokeswoman for the Iranian National Olympic Committee in Tehran said Iran's flag-bearer had been instructed not to compete, as reported by The Guardian. “This is a general policy of our country to refrain from competing against athletes of the Zionist regime and Arash Mir-Esmaili has observed this policy," she said. Mir-Esmaili himself was quoted by Iran's official news agency as saying he refused to compete out of sympathy with the Palestinian people.

Awarded For Cowardice

On his return to Iran, the then-Speaker of parliament, Gholamali Haddad, and a group of MPs welcomed Mir-Esmaili at the airport. Ayatollah Khamenei commented on the athlete’s conduct: “They made a lot of noise [about Mir-Esmaili’s refusal] so that it would be condemned, but this devout young Iranian outsmarted them with a fait accompli,” he told a group of Iranian athletes. President Mohammad Khatami awarded Mir-Esmaili a cash prize, the equivalent of $125,000, and Tehran’s mayor Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf named a building complex in Tehran after the athlete to thank him for “supporting the Palestinian people.”

But it’s hard for Iranian athletes to please Islamic Republic officials and state media, and sometimes even the slightest infraction has invited condemnation. For instance, During the 2016 International Shooting World Cup shooting competitions in Baku, Azerbaijan, in which teams from 80 countries participated, Iranian athlete Hossein Bagheri won a silver in the Men’s 10m Air Rifle, the first Iranian medal in the competitions. But when a photograph of him standing next to the Israeli bronze medalist Sergey Richter was published, the Young Journalists Club, part of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) referred to it as “a medal that smells of blood.” On his return to Iran, not only did Bagheri receive no thanks, he was summoned for questioning about why he had appeared next to an Israeli.

The Injury Excuse and the End of an Era

The years 1983 to 2006 were the “golden age” for the ban, the time when Islamic Republic officials proudly proclaimed that Iranian athletes would not compete against Israelis. But in 2006, this came to end. The International Olympics Committee (IOC) updated the Olympic charter, making it clear that if an athlete refused to compete against other athletes on political, religious, racial or ethnic grounds, that athlete would be banned from international competitions. Furthermore, the federation or the Olympics committee of that country would be fined and/or would be banned from competitions.

Iranian officials had no option but to change their tack. IRIB no longer trumpeted the words “defending the Palestinian right” — it didn’t want to be responsible for Iranian athletes and sports federations being banned from most international competitions.

Since 2006, the standard excuse of Iranian athletes for refusing to compete against Israelis has been injury. For instance, In the 2011 Greco-Roman Wrestling World Championship in Istanbul, the heavyweight Bashir Babajanzadeh beat his Russian opponent in the first round. But he withdrew in the second, giving injury as an excuse, despite the fact he was ahead 3-1. Had he stayed and won the second round he would have had to fight an Israeli challenger in the semi-finals.

But the injury excuse hasn’t always worked. For example, in the 2013 FILA Wrestling World Championships in Budapest, Mohammad Talaei, the head coach of Iran’s freestyle wrestling team, presented medical certificates excusing two young wrestlers from competing. They were due to face Israeli opponents. The attempt to excuse them met with the following response: “The medical committee of the competitions said that the third person would be accepted as injured only if his hand is cut off.”

During these years, a number of celebrated Iranian footballers playing for European teams have also been forced to withdraw from competing against Israeli teams.

In 2004, Vahid Hashemian, a footballer for the Iranian National Team who played for Germany’s Bayern Munich, refused to play for Bayern against Maccabi Tel Aviv Football Club — the same team that Masoud Shojaei and Ehsan Hajsafi faced this week — using injury as an excuse. Ashkan Dejagah, a German-Iranian dual citizen, used the same excuse in 2008 when he was part of the German National Youth Football Team. On the day the team was scheduled to play against its Israeli counterpart, he claimed that he had been injured. The then-German Interior Minister Wolfgang Schäuble criticized Dejagah for his behavior.

According to Iranian media, Mohammad Ali Karimi, a former member of Iran’s National Football Team, included a clause in his contract with Bayern Munich that relieves him of having to play against Israeli teams. The same clause has been included in contracts for Sardar Azmoun and Saeed Ezatolahi Afagh, who play for the Russian team Rostov, Alireza Jahanbakhsh with Dutch team Alkmaar, and Ashkan Dejagah, who now plays for the German club Wolfsburg.

Masoud Shojaei and Ehsan Hajsafi are now in danger of losing their chance to compete at the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia as part of Iran’s National Football Team. But if the Ministry of Sports, the Football Federation or any other Islamic Republic authority does ban them, it will be further evidence that, all along, Iranian athletes have refused to compete against Israeli athletes purely for political reasons, and not because of “injuries,” or because of being overweight or underweight or any other reason. This revelation could potentially lead to severe consequences for Iran’s Football Federation, and it could even face suspension from international events. And, if this happens, the chances are strong that other Iranian sports will also suffer. The excuses that have worked up to now will no longer be accepted.

This week’s developments pose a nightmare for government and sports officials in Iran. For Iranian athletes, however, it could signal a new future, new opportunities, and the end to their own decades-long ordeal.

Shahriar Nekoozad, Citizen Journalist

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments