“Who has put wisdom in the mind and who has given it understanding?”

– Job 38:36

The mind is a mystery that has engaged the inquiries of philosophers, theologians, and scientists for ages. Some have considered the mind as the part of us that is most divine, while others have spoken of it as the capacity which makes us most human. As much as the concept of the mind has occupied our thoughts, after 2000 years of reflection we are far from understanding what a mind actually is. Where does mind reside? Is your smartphone literally part of your mind? Does mind inhabit us or do we inhabit mind? Many philosophers and scientists today believe that you are essentially your brain and that “minds are simply what brains do.” Others, however, see the mind as a quality more subtle and more diffused. For them mind is like the air we breathe—it is both within us and around us and is extended throughout our relationships, tools, mediums of communication, and cultures.

Habitat for a Homunculus: Where does mind reside?

Socrates believed that one’s mind or psyche was beyond and yet within one’s body. Two thousand four hundred years ago, he reflected that the mind belongs to the ideal world of forms that do not change and never die. During one’s life the mind inhabits the body where it extends in three parts from the head to the heart. While the essential mind is unchanging, its time spent in the body leaves some residual corporeality that clings to it. Four hundred years after Socrates, the Apostle Paul offered a vital variation on the Socratic theme. For Paul the mind is both diffused outside the body and contained within, but it is the future glorified and resurrected body that is unchanging and immortal. Seeing the mind as a quality that is extended throughout cultures and belief systems, Paul encouraged his Roman and Corinthian readers to cultivate “the mind of Christ,” and to “renew their minds” according to the mind of God and not in conformity to the mind and patterns of the surrounding Roman culture.

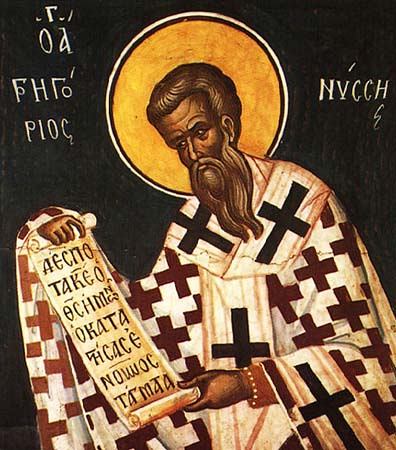

Gregory of Nyssa, writing in the 300s, explicitly defines Paul’s extended mind concept, viewing “the mind as fully integrated into our animal nature, but not enclosed within the body’s parameters.” Because he originated the concept that mind is extended beyond the brain and into the surrounding environment of information, some have proposed “Gregory as the patron saint of extended mind.”

-

Gregory of Nyssa

Extending the Mind through Media, Language, and Culture

Such competing theories of mind have continued to be debated to this day, and the concept of the extended mind that began with Gregory of Nyssa has gained increasing theoretical and scientific traction within the past few decades. The modern instantiation of the extended mind idea began with Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s. Observing a technological extension of consciousness through the various media and technologies that we create and that define us, McLuhan argued that “all media are extensions of some human faculty—psychic or physical—into the form of information.” The term “extended mind” itself was coined by physicist Robert K. Logan, who was a colleague of and close collaborator with Marshall McLuhan in the early 1970s. In a 1997 article entitled “The extended mind,” Logan made a case that the beginnings of language had created the mind or “extended the brain into a mind.”

Independently of Logan, a new generation of cognitive philosophers were reaching similar conclusions. Cognitive philosopher Andy Clark explored the implications of the extended mind in his book Being There, and then published a research report with David Chalmers on “the extended mind” in the following year. Here they contended that “the mind extends into the world” in cases where beliefs are partly constituted by features of the environment and when such beliefs drive cognitive processes. For example, if someone consistently relies on a notebook or a smartphone for an address or a number, then that same notebook or phone is part of that person’s cognitive process of remembering, and consequently part of that person’s mind.

"The idea of extended cognition maintains that part of your mind is literally on your smartphone when you use it to remember or to calculate."

As we use devices to navigate, compute, and recall for us, our memory and thought extends into the technologies we use. As we rely on our spouse who remembers appointments for us, our mind extends into another person who is reliably there for us. According to Clark and others, external technological and community-based supports for cognition act as scaffolding. Just as a construction crew uses scaffolding to support a building they are working on, we use technology and the people around us to support or extend mental processes such as memory and thought.

Philosophers of cognition Michael Kirchhoff and Julian Kiverstein add that culture likewise plays a crucial role in extending cognition and extending consciousness. Defending the position that “mind has no fixed boundary,” Kirchhoff and Kiverstein observe how individuals “come to be shaped by the cultural niches they construct,” and “cultural practice can play a part in the constitution of conscious experience.” As non-biological scaffolding complements and supplements the brain’s biological modes of processing, “the resulting hybrid cognitive systems are part biological and part technological, as well as cultural.”

The biological advantage of extending our minds is that we save precious time and energy by conserving metabolic resources that would otherwise be spent on figuring out a complex problem or learning a new task. Moreover, extending our minds enables us to widely share the content of our minds, and also experience the minds of others—even if they are long gone. The risk, though, is that when we rely on tools and media external to our brains for our computational skills and memories, we can literally lose our mind—or at least part of our mind—when the non-biological scaffolding is removed, lost, or altered. We may get lost without our phones to navigate for us, and in time our brains might even lose the ability to navigate without our phones. This is one reason why changes to our extended mind—such as moving to a new place or figuring out a new operating system—are so stressful and confusing. Our very selves are so tied up into the products and cultures that we have created, that we gain or lose our selves in our gaining or losing the world around us.

Brains Hardwired for Plasticity and Extension

Scientific research in psychology suggests that our dependence on the surrounding environment for our emergent conscious experience runs very deep. Even for simple tasks we constantly offload information processing onto the tools and environment around us to reduce work for our brains. Moreover, our brains are primed with a type of neuroplasticity that seamlessly allows us to offload these tasks with minimal effort. For example, when someone uses a long pole or rake to retrieve an object that is out of reach, their brain incorporates the pole into a new cognitive schema that literally perceives the tool as an extension of the body. Our brain updates itself to integrate a new and expanded body.

Despite the tendency in everyday life to think of ourselves as having a fixed personal identity and body shape, the human brain maintains a highly flexible representation of both the body and the self. Our brains are an interface between the mind inside and the minds outside, and the boundary or membrane between these minds is plastic and permeable. The more we use a given tool, and the more that tool is readily available, the more that tool becomes part of our extended body and extended mind. Whatever we happen to be touching, using, or interacting with becomes part of us. In a very real sense, then, my mind is not my own, but rather it is a product of the various contexts that I choose to inhabit and the things I choose to think upon. As Paul reflected many centuries ago, if I resolve to think upon whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable, and excellent, then that is what my mind becomes.