Magnitsky legislation

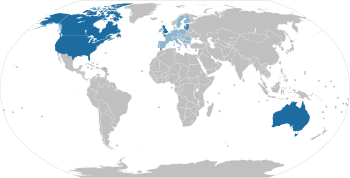

Magnitsky legislation refers to laws providing for governmental sanctions against foreign individuals who have committed human rights abuses or been involved in significant corruption. They originated with the United States which passed the first Magnitsky legislation in 2012, following the torture and death of Sergei Magnitsky in Russia in 2009. Since then, a number of countries have passed similar legislation such as Canada, the United Kingdom and the European Union.

Background[edit]

In 2008, Sergei Magnitsky was a tax accountant who accused Russian tax officials and law enforcement of stealing $230 million (~$320 million in 2023) in tax rebates from Hermitage Capital.[1] He, in turn, was arrested and jailed under the accusation of aiding tax evasion.[2] Allegedly beaten by police,[1] Magnitsky died in Matrosskaya Tishina detention facility in November 2009.[citation needed] In 2012, the United States Congress passed the Magnitsky Act, which imposed sanctions on the officials involved, following extensive lobbying by Magnitsky's former employer Bill Browder.[3]

Magnitsky legislation by country[edit]

Following the United States, Magnitsky legislation has been enacted in a number of territories, including the United Kingdom, Estonia, Canada, Lithuania, Latvia, Gibraltar, Jersey, and Kosovo.[4]

United States[edit]

The original Magnitsky Act of 2012 was expanded in 2016 into a more general law authorizing the US government to sanction those found to be human rights offenders or those involved in significant corruption, to freeze their assets, and to ban them from entering the US.[5]

Canada[edit]

| Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act (Sergei Magnitsky Law) | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Citation | S.C. 2017, c. 21 |

| Assented to by | Governor-General Julie Payette |

| Assented to | 18 October 2017 |

| Legislative history | |

| Bill citation | Bill S-226 |

| Introduced by | Sen. Raynell Andreychuk |

| First reading | 4 May 2016 |

| Second reading | 17 November 2016 |

| Third reading | 11 April 2017 |

| Committee report | Eighth Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade |

| First reading | 13 April 2017 |

| Second reading | 13 June 2017 |

| Third reading | 4 October 2017 |

| Status: Current legislation | |

| Part of a series on |

| Canadian citizenship and immigration |

|---|

|

|

In October 2017, Canada passed its own Magnitsky legislation known as the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act,[6][7] which the Parliament of Canada passed through a motion in March 2015.[8] The Act enables targeted measures against foreign nationals who, according to the Governor in Council (GIC), are, among others, "responsible for or complicit in gross violations of human rights; or are public officials or an associate of such an official, who are responsible for or complicit in acts of significant corruption."[7]

The regulations pursuant to the Act prohibit individuals and entities in Canada, as well as Canadians outside Canada, from, among others:

- "Dealing, directly or indirectly, in any property, wherever situated, of the listed foreign national;"

- "Entering into or facilitating, directly or indirectly, any financial transaction related to a dealing described above;"

- "Providing or acquiring financial or other related services to, for the benefit of, or on the direction or order of the listed foreign national;" and

- "Making available any property, wherever situated, to the listed foreign national or to a person acting on behalf of the listed foreign national."

Canada's sanctions under this Act are enforced by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Canada Border Services Agency, who also enforce related legislations such as the United Nations Act and the Special Economic Measures Act.[9]

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) provides the legislative authority for the Canadian government to deny entries to foreign nationals who are inadmissible to Canada pursuant to sanctions under the Act[9]

Russian president Vladimir Putin accused Canada of "political games" over the new Magnitsky law.[10] As such, the Act is perceived as damaging relations with Russia, especially with earlier warnings from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the law would be a "blatantly unfriendly step."[11][12][13] Russia had already placed Canada's former Foreign Minister, Chrystia Freeland, and 12 other Canadian politicians and activists on a Kremlin 'blacklist', barring them entry to "Russia because of their criticism of Russian actions in Ukraine and its annexation of Crimea," under the equivalent Russian law.[12]

Along with 30 Russian individuals, Canada's government subsequently targeted sanctions against 19 Venezuelan officials (including President Nicolás Maduro)[14] and 3 South Sudanese officials.[15] On 29 November 2018, Canada amended the Regulations to include 17 foreign nationals from Saudi Arabia, who, in the opinion of the GIC, are responsible for or complicit in blatant violations of internationally recognized human rights, particularly the torture and extrajudicial killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.[7] On 16 February 2018, Canada announced its sanctioning of Major-General Maung Maung Soe for being a "key military official" in Myanmar's human-rights violations against the Rohingya and the resulting flight of 688,000 Rohingya from their country.[16]

Sanctioned individuals include:

- 30 Russian officials

- 19 Venezuelan officials, including[14]

- 17 Saudi nationals, including[17]

- 3 Sudanese officials[18]

- Paul Malong Awan

- Malek Reuben Riak Rengu

- Michael Makuei Lueth

- 1 Burmese official[16]

On March 21, 2021, the Government of Canada promulgated the "Special Economic Measures (People’s Republic of China) Regulations"[19] under a related legislation, the Special Economic Measures Act,[20] on the basis that "gross and systematic human rights violations have been committed in the People’s Republic of China". Individuals sanctioned under this Regulation include Zhu Hailun, Wang Junzheng, Wang Mingshan, Chen Mingguo and Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.[21]

In Europe[edit]

Czechia[edit]

On October 16, 2022, the Czech Parliament approved Magnitsky legislation to act independently of the European Union's Magnistky sanctions. A particular concern was the Hungarian government of Viktor Orban, which has expressed pro-Russian sentiments and has managed to slow down EU-wide sanctions. Czechia is the fourth EU state (not including the United Kingdom, which passed a Magnitsky law before Brexit) to pass such legislation, after Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and this legislation will provide a legal basis for the Czech government to sanction human rights abusers. [22]

European Union[edit]

The European Parliament passed a resolution in March 2019 to urge EU and 28 member states to legislate similar with Magnitsky Act.[23][24][25][26]

On 9 December 2019, the EU Foreign Affairs and Security Policy High Representative Josep Borrell, who is the chief co-ordinator and representative of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) within the EU, announced that all member states had "agreed to launch the preparatory work for a global sanctions regime to address serious human rights violations, which will be the European Union equivalent of the so-called Magnitsky Act of the United States."[27][28]

On 7 December 2020, the European Union passed[29] the European Magnitsky Act,[30] which will allow the organization to "freeze assets and impose travel bans on individuals involved in serious human rights abuses".[31]

Among the criteria for sanctions are: genocide, crimes against humanity, torture, slavery, extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrests, or detentions. The act establishes the following procedure to impose sanctions. Entitled to submit proposals for sanctions implementations, review or amendment are each of the member states and also the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The decision is to be taken by the Council of the European Union.[32]

Estonia[edit]

On 8 December 2016, Estonia introduced a new law that disallowed foreigners convicted of human rights abuses from entering Estonia. The law, which was passed unanimously in the Estonian Parliament, states that it entitles Estonia to disallow entry to people if, among other things, "there is information or good reason to believe" that they took part in activities which resulted in the "death or serious damage to health of a person."[33]

Gibraltar[edit]

In March 2018, Gibraltar passed Magnitsky legislation.[34]

Jersey[edit]

Jersey passed its Sanctions and Asset Freezing (Jersey) Law (SAFL) in December 2018, going into effect on 19 July 2019.[35][36] The new law reincorporated the effects of the previous Terrorist Asset-Freezing (Jersey) Law 2011 (TAFL) and the United Nations Financial Sanctions (Jersey) Law 2017 (UNFSL), which it repealed.

Kosovo[edit]

On 29 January 2020, Kosovo passed its Magnitsky law,[37] which was announced by Foreign Minister Behgjet Pacolli on Twitter.[38]

Lithuania[edit]

On 16 November 2017, the 8th anniversary of Sergei Magnitsky's death, the Parliament of Lithuania (Seimas) unanimously passed their version of Magnitsky legislation.[39]

Latvia[edit]

On 8 February 2018, the Parliament of Latvia (Saeima) accepted attachment of a law of sanctions, inspired by the Sergei Magnitsky case, to ban foreigners deemed guilty of human rights abuses from entering the country.[40]

United Kingdom[edit]

On 21 February 2017, the UK House of Commons unanimously passed an amendment to the country's Criminal Finances Bill inspired by the Magnitsky Act that would allow the government to freeze the assets of international human rights violators in the UK.[41][42]

On 1 May 2018, without opposition, the Commons added the "Magnitsky amendment" to the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill, which would allow the British government to impose sanctions on people who commit gross human rights violations.[42][43]

Australia[edit]

Member of Parliament Michael Danby introduced a Magnitsky bill in the Australian parliament in December 2018 but was lapsed in April 2019.[44]

In December 2019, the Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs, Marise Payne, asked the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Human Rights Sub-committee to inquire into the use of targeted sanctions to address human rights abuses.[45][46] In 2020, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was asked about the possibility of Australia stopping the issuance of visas to Huawei Technologies employees for their complicity in China's human-rights violations, including in Xinjiang. The department stated that the inquiry into setting up Magnitsky-like rules was due to report to later in the year.[47] Meanwhile, Australia was urged by the Bill Browder, who lobbied the U.S. Magnitsky Act into Congress, to pass its own Magnitsky law or "risks becoming "a magnet for dirty money" from abusers and kleptocrats across the globe"[48]

In December 2020, the Joint Standing Committee tabled its report and recommended that the Australian Government "enact stand alone targeted sanctions legislation to address human rights violations and corruption, similar to the United States' Magnitsky Act 2012 which provides for sanctions targeted at individuals rather than existing sanctions regimes which are more often directed at states".[45] In August 2021, the Australian Government announced that it would adopt a sanctions law similar to the U.S. Magnitsky Act that allows targeted financial sanctions and travel bans against individuals for egregious acts of international concern that could include the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, gross human rights violations, malicious cyber activity, and serious corruption. Australia would reform its laws to expand country-based sanctions and specify the conduct to which sanctions could be applied by the end of the year.[49] Similar Magnitsky private member bills had also been introduced by Labor's Kimberley Kitching and Greens' Janet Rice. The government's legislation, introduced and passed in November 2021 and named Autonomous Sanctions Amendment (Magnitsky-style and Other Thematic Sanctions) Act 2021, commenced on 8 December 2021.[50]

In February and March 2022, in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Australia initially did not use the new law but instead used other pre-existing sanction laws to impose travel and financial sanctions on Russian individuals and entities.[51][52][53] However, Australia used its Magnitsky law for the first time on 29 March 2022 to sanction 39 Russian individuals "accused of serious corruption and involvement in the death and abuse" of Magnitsky.[54][55]

Russian response[edit]

In 2012, the Russian government responded to the new American Magnitsky Act by passing the Dima Yakovlev Law (long title: On Sanctions for Individuals Violating Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms of the Citizens of the Russian Federation);[56][57] banning Americans from adopting Russian children; and providing for sanctions against U.S. citizens involved in violations of the human rights and freedoms of Russian citizens.[58][59]

Pending legislation[edit]

Magnitsky legislation is under consideration in a number of countries.

Moldova[edit]

In July 2018, a Magnitsky bill was introduced into the Moldovan parliament,[60] mandating sanctions against individuals who "have committed or contributed to human rights violations and particularly serious acts of corruption that are harmful to international political and economic stability."[61] As of January 2020, it had not been acted upon;[61][62] however, the DA Platform party is still pushing for its adoption, although the ACUM coalition has dropped its demand for passage.[62]

Ukraine[edit]

In December 2017, there was a Magnitsky bill introduced into the Ukrainian parliament.[63] The bill would have given authority to sanction foreign individuals who grossly violate human rights through the use of visa bans, asset freezes, and restrictions on asset transfer.[61] However the bill was quickly tabled, and in September 2018, it was removed from the legislative agenda.[61]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Q&A: The Magnitsky affair". BBC News. 11 July 2013.

- ^ Aldrick, Philip (19 November 2009). "Russia refuses autopsy for anti-corruption lawyer". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009.

- ^ Palmer, Doug (14 December 2012). "Obama signs trade, human rights bill that angers Moscow". The Daily Star. Lebanon. Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012.

- ^ Ochab, Ewelina U. (17 May 2020). "On Targeted Sanctions To Address Attacks Against Journalists And Media Freedom Violations". Forbes. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020.

- ^ The Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act "The US Global Magnitsky Act: Questions and Answers". Human Rights Watch. 13 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017.

- ^ Zaman, Kashif (9 November 2017). "Canada enacts Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act - Implications for compliance with Canadian anti-money laundering requirements". sler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act." Canada and the World. Ottawa: Government of Canada. October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Clark, Campbell (25 March 2015). "All parties signal support for Magnitsky law to sanction Russian officials". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Canadian sanctions legislation." Canada and the World. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 18 September 2020.

- ^ Blanchfield, Mike (20 October 2017). "Vladimir Putin accuses Canada of 'political games' over Magnitsky law". Global News. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Canada Passes Version Of Magnitsky Act, Raising Moscow's Ire". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b Sevunts, Levon (18 May 2017). "Russia warns Canada over 'blatantly unfriendly' Magnitsky Act". CBC News. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017.

- ^ "As Canada's Magnitsky bill nears final vote, Russia threatens retaliation". CBC News. Thomson Reuters. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017.

- ^ a b Global Affairs Canada. 6 November 2017. "Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials - Case 2." Government of Canada.

- ^ "Russia, South Sudan and Venezuela are Canada's 1st targets using sanctions under Magnitsky Act". CBC News. 3 November 2017. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017.

- ^ a b Global Affairs Canada. 16 February 2018. "Canada imposes targeted sanctions in response to human rights violations in Myanmar." Government of Canada.

- ^ Global Affairs Canada. 29 November 2018. "Jamal Khashoggi case." Government of Canada.

- ^ Global Affairs Canada. 6 November 2017. "Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials - Case 1." Government of Canada.

- ^ Special Economic Measures (People’s Republic of China) Regulations (Regulations SOR/2021-49). Administrator of the Government of Canada in Council. 21 March 2021.

- ^ Special Economic Measures Act (Legislation S.C. 1992, c. 17). Senate and House of Commons of Canada. 4 June 1992.

- ^ Global Affairs Canada. 22 March 2021."[1]." Government of Canada.

- ^ "billbrowder on Twitter: "BREAKING: This evening the Czech President signed the Czech Magnitsky Act into law. It's a done deal. Thank you @JanLipavsky, my friend, ally and Czech Foreign Minister who made this happen. This will be used to do lots of good things for victims of human rights abuse"". Twitter. 7 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Rikard Jozwiak (26 April 2018). "MEPs Urge EU Magnitsky Act To Tackle Kremlin's 'Antidemocratic' Activities". Radio Free Europe. Archived from the original on 26 May 2018.

- ^ "European Parliament resolution on a European human rights violations sanctions regime". EU Parliament. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "MEPs call for EU Magnitsky Act to impose sanctions on human rights abusers". EU Parliament. 14 March 2019.

- ^ Rikard Jozwiak (14 March 2019). "European Parliament Urges EU To Adopt Legislation Like Magnitsky Act". Radio Free Europe.

- ^ "The Magnitsky Act Comes to the EU: A Human Rights Sanctions Regime Proposed by the Netherlands". Netherlands Helsinki Committee. December 2019. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020.

- ^ "EU ministers break ground on European 'Magnitsky Act'". euractiv.com. 10 December 2019.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "EU approves its 'Magnitsky Act' to target human rights abuses | DW | 07.12.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Legislative train schedule: European Magnitsky Act". European Parliament. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "EU agrees its own 'Magnitsky' regime to sanction human rights abuses". euronews. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Norman, Laurence (27 November 2020). "After U.S. Push, EU Set to Target Human-Rights Violators". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Rettman, Andrew (9 December 2016). "Estonia joins US in passing Magnitsky law". EUobserver. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016.

- ^ Graham, Chris (11 March 2018). "The Magnitsky Act: How a lawyer's death spurred a global fight against Russian corruption and abuses". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020.

Last week Gibraltar became the latest country to pass the law ...

- ^ "Sanctions and asset-freezing law". The Jersey Financial Services Commission (JFSC). July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- ^ Byrne, Rob (6 December 2018). "Putin critic welcomes "dirty"money law". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- ^ Bami, Xhorxhina (29 January 2020). "Outgoing Kosovo Govt Adopts Magnitsky Act". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020.

- ^ Pacolli, Behgjet (29 January 2020). "I'm proud that today the government of #Kosovo established the Kosovo #Magnitsky Act sanction foreign government officials implicated in human rights abuses anywhere in the world in line w/@StateDept practice. #Kosovo takes strategic step align its foreign policy w/United States". Twitter. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Lithuania: Parliament Adopts Version of Magnitsky Act". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Latvia Becomes Final Baltic State to Pass Magnitsky Law". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. 9 February 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "UK House of Commons Passes the Magnitsky Asset Freezing Sanctions". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- ^ a b Smith, Ben; Dawson, Joanna (27 July 2018). "Magnitsky legislation" (PDF). House of Commons.

- ^ "UK lawmakers back 'Magnitsky amendment' on sanctions for human rights abuses". Reuters. 1 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019.

- ^ "International Human Rights and Corruption (Magnitsky Sanctions) Bill 2018". Parliament of Australia. December 2018. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b Wade, Geoff (20 August 2021). "Australia and Magnitsky legislation". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Philip Citowicki (2 July 2020). "Slow Progress Toward an Australian Magnitsky Act". The Diplomat.

- ^ Varghese, Sam. 18 July 2020. "Australia looking to copy US and adopt Magnitsky-style human rights regime." ITWire.

- ^ Ben Doherty (17 February 2020). "Australia urged to pass Magnitsky human rights law or risk becoming haven for dirty money". The Guardian.

- ^ "Australia to adopt Magnitsky style sanctions law". Reuters. 5 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Autonomous Sanctions Amendment (Magnitsky-style and Other Thematic Sanctions) Act 2021". Australian Government - Department of Foreign Affairs and Tradedate=8 August 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Victorian Labor senator Kimberley Kitching dies suddenly in Melbourne aged 52". ABC News. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Australia to impose harsh financial sanctions, travel bans on Russia over 'invasion' of Ukraine". Sydney Morning Herald. 23 February 2022.

- ^ Ferris, Leah (28 February 2022). "Sanctions imposed on Russia in response to aggression against Ukraine – how are they imposed under Australia's sanctions laws?". Parliament of Australia.

- ^ "Amid invasion of Ukraine, Australian government announces Magnitsky-style list to target corrupt Russians". ABC News. 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Australia's first Magnitsky-style sanctions". Australian Department of Foreign Affair and Trade. 29 March 2022.

- ^ "On Sanctions for Individuals Violating Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms of the Citizens of the Russian Federation"

- ^ Englund, Will (11 December 2012). "Russians say they'll name their Magnitsky-retaliation law after baby who died in a hot car in Va". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012.

- ^ "A law on sanctions for individuals violating fundamental human rights and freedoms of Russian citizens has been signed". Office of the President of Russia. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil; Kramer, Andrew E. (12 July 2017). "Natalia Veselnitskaya, Lawyer Who Met Trump Jr., Seen as Fearsome Moscow Insider". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017.

- ^ Cappello, John (21 November 2018). "Moldova Considers Adopting the Global Magnitsky Act". Real Clear Defense. RealClear Media Group. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Shagina, Maria (26 April 2019). "Magnitsky-style sanctions in the Eastern Partnership". The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

- ^ a b "DA platform suggests adopting analog to Magnitsky law in Moldova". Infotag. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- ^ "Magnitsky Act has been introduced into Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament)". Samopomich (Самопоміч). 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017.