Texas Populists Fought for Shared Solutions

The 19th-century political movement has influenced policies and politicians long after it faded from power.

Photo by Mark Graham

Texas Populists Fought for Shared Solutions

The 19th-century political movement has influenced policies and politicians long after it faded from power.

Last March, a headline in The Atlantic asked, “Does Anyone Know What ‘Populism’ Means?” It’s a question Gregg Cantrell is eager and well-equipped to answer.

In his book The People’s Revolt: Texas Populists and the Roots of American Liberalism (Yale University Press, 2020), Cantrell chronicles the establishment of the Texas People’s Party and the rise of the related Populist movement in the 1890s. This regional farmers’ coalition for economic justice had an outsized legacy, espousing ideas that would reverberate throughout the following century in legislation such as the New Deal and the Great Society.

He contrasts that movement’s groundbreaking “big tent” principles and key players with today’s lowercase “p” populists, as embodied by such wildly divergent and controversial figures as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. “The word populism has been bent and twisted almost beyond recognition today,” Cantrell said. “It has simply become shorthand for demagoguery.”

He contrasts that movement’s groundbreaking “big tent” principles and key players with today’s lowercase “p” populists, as embodied by such wildly divergent and controversial figures as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. “The word populism has been bent and twisted almost beyond recognition today,” Cantrell said. “It has simply become shorthand for demagoguery.”

In Populism’s heyday in the mid-1890s, Texas was home to more Populists than any other state. As the Erma and Ralph Lowe Chair in Texas History and former president of the Texas State Historical Association, Cantrell can explain why Populism found such early and fervent favor in Texas.

“It was a national movement. But its principal strength was in Texas as well as the Plains states and Mountain West,” he said. “It was really born on the frontier, a place where government at all levels was weak and people often had to take matters into their own hands.”

Farm to Labor Movement

Cantrell spent 15 years on The People’s Revolt, drawing on newly digitized newspaper databases and his earlier research on pivotal figures of the movement.

“Gregg is at once a Texas historian and a historian of Texas,” said Andrew Graybill, director of the Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University. “He knows the story of the Lone Star State inside and out, both as a native son as well as one of its leading chroniclers. At the same time, he is able to place Texas history in its wider national context, which is precisely what he has done so well with The People’s Revolt.”

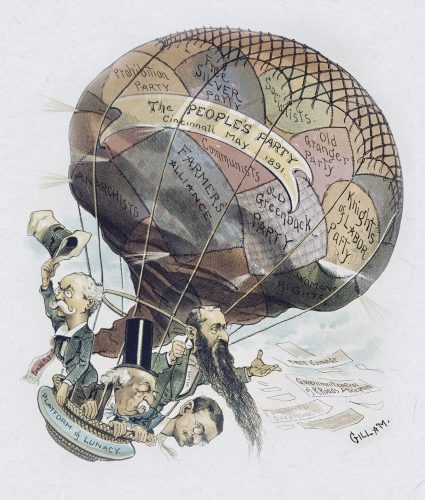

A political cartoon critical of the Populist movement was the cover of the June 6, 1891, issue of Judge magazine. While the cartoon satirized the union of farmers, laborers and supporters of expanded opportunity, the People’s Party found success largely because it emphasized shared problems — and practical solutions — for the average Joe. Illustration by Bernhard Gillam | Photo by Fotosearch | Getty Images

At its core, Populism was a political crusade for economic justice for the average Joe at the time of large-scale industrialization during the Gilded Age. “The mammoth new corporations — steel, railroads, oil, etc. — received all sorts of favors and protections from the government,” Cantrell said, “favors and protections that enabled them to ride roughshod over workers and farmers.”

Texas farmers rallied against these forces in 1877 by establishing the Farmers’ Alliance. To bolster members’ economic positions in the face of concentrated corporate power and control of commodity prices, the alliance launched a broad cooperative effort across the state. More than 300 co-op ventures opened, including cotton gins, grain mills, warehouses and more than 130 stores.

While these market endeavors largely failed in the face of opposition from the commercial sector, the alliance succeeded on another front. “[It] created what sociologists have called movement culture,” Cantrell said, “a mass mobilization of ordinary people committed to common goals.”

As an economic depression persisted in the late 1880s and early 1890s, with government at all levels virtually unresponsive to the plight of the working class, the Farmers’ Alliance found common cause with the growing labor movement, which sought to protect industrial workers from exploitation.

The alliance lobbied the major political parties for measures to benefit farmers and laborers, such as regulation of the railroads and protections for organized labor through collective bargaining rights and an eight-hour workday, among other measures.

The alliance also put forth an innovative proposal called the Subtreasury Plan. “It would thoroughly revamp the nation’s system of agricultural credit and take the country off the gold standard,” Cantrell said. Doing so would make the nation’s money supply more flexible, relieving the pervasive credit shortage faced by farmers.

However, as a private organization, the Farmers’ Alliance did not have the power to put its plans into action, Cantrell said. “That’s when they concluded a new party was needed.”

A Place at the Table

In 1891, the state’s Populist groundswell gave birth to the Texas People’s Party.

The political landscape was fertile ground for a third party. “Texas was the newest of the Southern states, with a good bit of Western heritage,” Cantrell said, “so political institutions, particularly the Democratic Party, were perhaps not as entrenched there.”

Populists “believed that all humans should have dignity, whatever their economic status, gender or race.”

Gregg Cantrell

From the start, the party’s approach to gender, religion and race was distinct and ahead of its time, a forerunner of inclusive modern liberalism. Populists “believed that all humans should have dignity, whatever their economic status, gender or race,” Cantrell said. “Not every Populist always lived up to these ideals, but you can see the culture of dignity reflected in much of their rhetoric and actions. Among the most obvious signs of it was their welcoming of women into political gatherings, inviting them to speak at conventions and to contribute editorials to Populist newspapers.”

He said this perspective of dignity for all stemmed in large part from the fact that the great majority of Texas Populists were evangelical Protestants; their political beliefs mirrored their religious beliefs. Yet they welcomed those with nontraditional faith practices as well. “Populists were surprisingly tolerant of religious dissent,” Cantrell said. “Even so-called free thinkers — that is, atheists or agnostics — found a home in the party.”

The fractious issue of race in the 1890s complicated the party’s outreach to African Americans and Mexican Americans. Appeals for their votes usually were presented in terms of shared economic interests, Cantrell said. “It is really important [to note that Populists] treated members of those communities with far more common decency than Democrats did.”

John Rayner, a classically educated and formerly enslaved person, was among the orators and organizers who strove to make the party a biracial coalition, but he ran up against a stark political reality.

“In American politics, you have to win races ultimately, and white Populists knew that to be too progressive in matters of race was to invite white backlash,” Cantrell said. “So the Populists tried to do the impossible: to extend the hand of political friendship and civil citizenship to Blacks without inviting what in the day was called social equality.”

On the Ballot

The Texas People’s Party fielded candidates for state offices in 1892 and 1894, with Judge Thomas Nugent at the top of the ticket both times as its gubernatorial contender. “Nugent was one of the remarkable figures in Texas political history,” Cantrell said. “You rarely find a major political figure whose private and public lives were so remarkably free from any hint of corruption or even self-interest.

“He was the public face that Populists wanted to put forward to the public. They were in essence saying, ‘Look, this is the sort of leader you’ll get from the People’s Party.’ ”

In 1894, Nugent garnered 36 percent of the vote for Texas governor, and 24 Populists were elected to the Legislature, establishing the party as the major opponent to the Democrats in the Lone Star State.

Historian Gregg Cantrell spent 15 years researching and writing The People’s Revolt, which chronicles the rise and fall of the Populist movement in Texas. Photo by Mark Graham

Success at the polls would not last long. One economic issue for Populists had long been the uncoupling from the gold standard to loosen the money supply and make credit more available to the average working person. So when William Jennings Bryan gave his legendary “Cross of Gold” speech at the Democratic National Convention in 1896, he co-opted a plank in the Populists’ platform.

Deflated, delegates at the Populist national convention declined to field their own presidential candidate and endorsed Bryan instead, Cantrell said. “This was a fatal dagger in the side of Populists in places like Texas who had built their movement largely on opposition to Democrats.”

The party never recovered from the rift. By 1900, both the Texas and national Populist movements were effectively dead.

Their ideas, however, were not.

Old Roots of New Deals

“There’s a long list of Populist ideas that eventually came to fruition in the 20th century,” Cantrell said. “Some of these found expression in Progressive reforms. Some had to wait for the New Deal. And still others didn’t find full expression until Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society.” (Perhaps it’s no coincidence that President Johnson was the grandson of one of the leaders of the Farmers’ Alliance.)

Major legislation — from the National Labor Relations Act, which gave private-sector workers the right to organize, to the Social Security Act, to the National School Lunch Program — had roots in Populism’s quest for public remedies to economic inequality.

“All of these policies were grounded in the basic belief that in a modern capitalist economy, certain widely shared public problems demanded public solutions,” Cantrell said. “The sturdy individual pulling him- or herself up by their bootstraps was not a realistic strategy for countering corporate power.”

There is a major disconnect, however, between the Populism practiced by the Texas People’s Party and the small “p” populism of modern politics.

“In one sense, if you think of populism as a political style — an appeal to the common man and woman against the malignant power of an out-of-touch, corrupt elite — then you can see how the term gets applied to a wide range of political figures, from Huey Long to George Wallace to Bernie Sanders to Donald Trump,” Cantrell said, “and to foreign figures like Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, Marine Le Pen of France, Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil or Viktor Orban of Hungary.

Members of the Texas People’s Party called for public remedies for economic inequality and thus shaped American political history, says Gregg Cantrell. Photo by Mark Graham

“But it matters a great deal how and why a so-called populist is making his or her populist appeal. Is the political figure doing it cynically, to grab or maintain power, with no real interest in the welfare of the people to whom the appeals are being made? In other words, is populism just a cover for demagoguery? Or is the populist genuinely concerned about championing the interests of ordinary citizens against the predations of a corrupt, unresponsive establishment?

“My book suggests that the original Texas Populists, with a few notable exceptions, were sincere in their populism. However, most leaders today who are identified as populists, with some notable exceptions, are cynical in their populism. Their appeals are to the fears and prejudices of the masses whom they purport to represent, and their true goals are to gain and hold on to power.

“Indeed, many of today’s so-called populists are profoundly anti-democratic, the antithesis of the Texas Populists I’ve written about.”

Your comments are welcome

16 Comments

Dr. Cantrell’s thoroughly researched The People’s Revolt is the defining book on Texas populism.

Again thanks Greg for your presentation of my great grandfather in this historic movement

Again thanks Greg for your presentation of my great grandfather in this historic movement

It’s been a pleasure knowing ypu

Thanks so much for this interesting and informative article! It’s refreshing to hear about Texas as such a force for liberal ideas. I hope individuals there can come together again and reject self-serving politicians, and elect some new people who will support all people, rather than wasting large sums of public funds on publicly stunts, and promoting policies to turn residents against each other.

Who are the notable exceptions among today’s populists who are not cynical and exploitative wannabe demagogues.

Thank you so much. Now I understand the politics of my grandparents and the area in which I grew up much better – the South Plains of Texas. They were farmers on both sides way down the line. They were kind, fair, decent people who were the backbone of Texas.

Thank you for a true definition of “populist.” Having been puzzled by the word’s being applied to Donald Trump, I recognize the definition that I learned years ago. Also learning that LBJ’s family was involved helps me better understand his relationship to the Voting Rights bill. Time for Texas to return to its populist roots.

Blammo!…bulls-eye! A clean shot aimed at people like myself whose poor vocabulary almost makes it impossible to “get” the real meaning (gist) of what we are reading. Couple that ‘disability’ with the darth of American history , about those years, being taught in our public schools, and we are left with relative boneheads who would believe Biden lost the election. Thank you “Kristin” for presenting this in such a manner that I think…..,”I get it”.

Alex

aka: The Mad Russian 12A

While Bernie Sanders may be deemed a “populist,” lumping him in with the others mentioned is a bit of a stretch. He has nothing in common with the anti-democratic, illiberal autocratic charlatans who are included.

The political power of the people for the people and by the people must be renewed, realized and recognized as a force again in America or true democracy in this country will cease to exist. We must pass the John Lewis Voting Bill and force Constitutional decisions-in the Supreme Court which are presently lacking. The Constitution must be recognized as

superseding State law or we are no longer The United States of America.

The time is right for a new party in US politics. The Populist Party would be historically meaningful and a reverant prayer of hope for the average Joe.

This is a fascinating history that I was completely unaware of. That this Progressive (in the modern sense) populist movement originated and spread in the regions of the country we now think of as “deep Red” is a huge surprise. Of course, history is full of surprises and it’s unfortunate most of us have such a weak understanding of our own.

I look forward to reading Mr. Cantrell’s book, The People’s Revolt.

I found your review of what happened to be educational and inspiring.

For when we are tempted to give up, a dramatic change of direction is possible.

I am grateful for this history of populism in Texas–glad it reflects the thinking of my folks–we deserve respect, fairness, dignity, even if we are poor and hard-working people. We need such a movement now as we have so many self-aggrandizing blowhards at every level who do not seem to value all Americans or respect democracy and have faith in the electorate.

Thank you for your comment, Alice Blood.

Great article…can’t wait to read the book.

As women’s rights are being ripped apart by the Supreme Court of the United states, we need all women to mobilize a movement to take them to task on their inhumane treatment of women. All women need to get to the voting booths and vote everyone out who doesn’t champion women’s rights. We have to be outraged about what some power hunger people are doing or not doing to preserve our democracy for all people and eliminate all the conspiracy theories that do not represent the truth of this nation. I will be on the front lines motivating women to fight for our rights and not the rights men think women should have. God save our democracy!!

Related reading:

Where Academic Teams Shine Together

We’re home to extraordinary academics working to make the greater good even greater.

Features

Jim Wright Journals Offer Inside View of Political Life

In diaries left to TCU, the congressman talks politics and power.

Research + Discovery

‘Rabble’ Rouses Interest in 1960s Language

English professor combs archives across the country to document 1960s social movements.