A Scoping Review on Work Experiences of Nurses After Being Diagnosed With Cancer

Problem Identification: To map key concepts underpinning work-related studies about nurses with cancer and identify knowledge gaps.

Literature Review: A search was conducted in the PubMed®, CINAHL®, and PsycINFO® databases for articles about nurses with cancer and work-related topics published through March 2023.

Data Evaluation: The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist was used to report results, and the JBI critical appraisal tools were used to assess the quality of studies. Eleven articles were included.

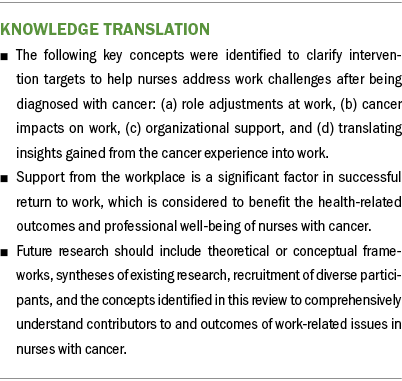

Synthesis: The following four critical concepts were identified: role adjustments at work, cancer impacts on work, organizational support, and translating insights gained from cancer experience into work. Research gaps identified by the scoping review were a lack of theoretical or conceptual frameworks, lack of syntheses of main ideas, and lack of clear data about participants’ socioeconomic status across studies.

Implications for Research: Minimal research exists to map predictors, outcomes, or intervention targets to guide organizational strategies to support nurses’ retention in the nursing workforce. A guiding framework, recruitment of diverse nurses, and focus on the four critical concepts identified in this scoping review are suggested for future research.

Jump to a section

Globally, nursing is the largest profession in the healthcare workforce, contributing tremendously to healthcare systems and population health. According to the World Health Organization (2020), there were 19.3 million nurses globally in 2018, comprising 59% of all healthcare professionals. However, the nursing workforce faces challenges, including a projected shortage of 5.7 million nurses by 2030 (World Health Organization, 2020), and nurses face elevated risks of poor health because of their work and work environment (Wills et al., 2020).

Nurses experience work hazards that elevate their risk of getting cancer (Ekpanyaskul & Sangrajrang, 2018; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2021; Papantoniou et al., 2018; Purdue et al., 2015; Ratner et al., 2010; Wegrzyn et al., 2017). The effects of cancer on nurses’ experience of and ability to work can be substantial, and they may face difficulties when they attempt to remain working or return to their nursing positions after cancer diagnosis or treatment (de Boer et al., 2020; Goss et al., 2014). Understanding of work-related issues among nurses with cancer is lacking. This scoping review aims to clarify the key concepts and knowledge gaps in work-related studies of nurses with cancer.

Background

The nursing profession faces persistent challenges, including an aging workforce, retirement, and burnout, which influence nurses’ health and affect the quality of patient care (Andel et al., 2022; Haddad et al., 2023; World Health Organization, 2020). Smiley et al. (2021) found that more than 20% of practicing nurses in the United States planned to retire from healthcare settings within five years. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected nurses’ well-being and exacerbated nursing shortages in the United States and around the world (Buchan et al., 2022; Galanis et al., 2021; Kurtzman et al., 2022). In addition, the global nursing workforce is 89% female (Smiley et al., 2021); female nurses are at greater risk for cancer than the general female population because of multiple cancer risk factors, including greater likelihood of occupational hazards and unhealthy lifestyles (Ekpanyaskul & Sangrajrang, 2018; Friedenreich et al., 2021; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2021; Papantoniou et al., 2018; Purdue et al., 2015; Ratner et al., 2010). About 9.2 million women developed cancer in 2020, according to the Global Cancer Observatory (Ferlay et al., 2023). Taken together, the size of the female population with cancer and the challenges faced by the nursing workforce heighten the need for more attention to the population of nurses with cancer and underscore the importance of providing the necessary support for them to stay in the workforce.

An international survey of nurse leaders from 33 countries indicated that nurses’ work and work environments put them at risk for poor health (Wills et al., 2020). Many nurses are exposed to toxic chemicals and shift work, which may disrupt day-to-day circadian rhythms (Ekpanyaskul & Sangrajrang, 2018; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2021; Papantoniou et al., 2018; Purdue et al., 2015; Ratner et al., 2010; Wegrzyn et al., 2017). Nurses working in the oncology setting have an increased risk of breast cancer and rectal cancer compared to nurses working in non-oncology settings (Ratner et al., 2010). Nearly 60% of nurses in the United States work in hospitals and may work night shifts. Years of night work increase the risk of breast or colorectal cancer experienced by nurses (Gómez-Salgado et al., 2021; Papantoniou et al., 2018; Purdue et al., 2015; Wegrzyn et al., 2017). In addition, a survey of U.S. nurses found that about one-half of nurses (57.5%) report being overweight or obese, and about four of five nurses (80.1%) have a sedentary lifestyle (Ross et al., 2019). These figures are higher than the global and U.S. profiles (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022; Ritchie & Roser, 2017). These factors increase the risk of multiple common cancers, including colon, gynecologic, lung, breast, and thyroid cancer (Friedenreich et al., 2021). Despite the importance of nurses’ well-being and their outsized participation in the healthcare workforce, research exploring the challenges faced at work by nurses with cancer after their diagnosis is lacking.

Numerous factors influence the decision to return to work in individuals with cancer, including patient-related, cancer-related, and work-related factors. Individuals with cancer with older age, lower income at diagnosis, more comorbidities, cancer recurrence, and lack of work accommodations tend to have worse work outcomes after a cancer diagnosis (Butow et al., 2020; Dorland et al., 2018; Duijts et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2021). Although 73% of cancer survivors who were employed at the time of diagnosis were able to return to work, they reported decreased working hours (12%–52%), lower income (21%), and need for work accommodations (13%–55%) (de Boer et al., 2020). Although a high rate of return to work (95%) has been noted for healthcare professionals diagnosed with breast cancer in the first year following completion of cancer treatments, most required work accommodations, with 90% requiring temporary work adjustments and 10% of those requiring permanent adjustments (Goss et al., 2014). Being employed benefits individuals with cancer and fulfills values like pursuing personal development; maintaining a sense of normalcy, identity, and accomplishment; and staying connected to others and society (Butow et al., 2020). In addition, being employed is a social determinant of health associated with better quality of life, higher self-esteem, fewer depressive symptoms (Blinder & Gany, 2020; McPeake et al., 2019; Seifart & Schmielau, 2017), and lower financial burden (Butow et al., 2020; Guy et al., 2013). Supporting nurses with cancer to stay in the nursing workforce might be able to reduce individual financial burdens, which have been shown in the general cancer population, as well as mitigate the costs to healthcare systems and loss of societal productivity (Blinder & Gany, 2020; Mols et al., 2020; Nekhlyudov et al., 2016).

The effects of a cancer diagnosis on work have been extensively researched, but key concepts for nurses with cancer have yet to be clarified. More attention is needed to clarify the challenges faced by nurses with cancer so that appropriate interventions can be implemented to support them in choosing to return to work in clinical settings. Therefore, a scoping review of the state of the science with a focus on work-related issues in nurses with cancer is required. A scoping review can help researchers explore existing evidence for a topic when the scope and concepts related to the topic are not well defined. A scoping review can contribute to and guide future research and practices in a specific topic area by clarifying the concepts and identifying knowledge gaps (Munn et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2020). Because of the paucity of research focused on the concerns of nurses with cancer returning to work after a diagnosis, mapping out the landscape of existing research could greatly improve the ability to understand the needs of this population. This scoping review (a) examined and mapped the work-related concepts in nurses with cancer and (b) identified knowledge gaps and evidence to inform future work-related studies in this population.

Methods

Design, Search Methods, and Search Outcomes

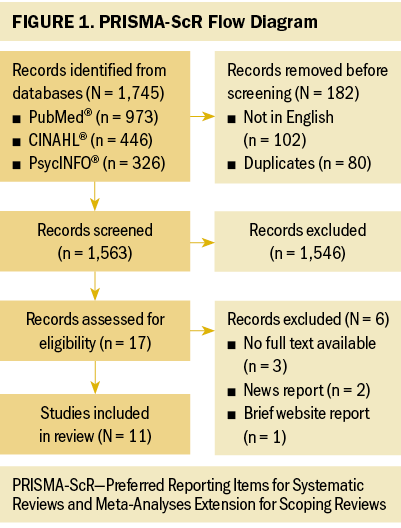

This scoping review followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist to describe the rationale for the review, conduct a systematic search, and report results (Page et al., 2021; Tricco et al., 2018).

The researchers worked with an experienced librarian from the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania to identify keywords and frame the search strategies. The keywords nurses, cancer, work, and their derivatives were used to search for articles in the PubMed®, CINAHL®, and PsycINFO® databases from the earliest available time through March 24, 2023. The search strategies were consistent and only slightly adjusted across all three databases based on the different features of each. Inclusion criteria were being in English, being a peer-reviewed article or conference abstract, having the full text available, discussing work-related issues or outcomes, and having a study population that met the following criteria: (a) had valid RN licenses at the time of study recruitment, (b) had been treated for any cancer type, (c) worked in clinical healthcare settings (e.g., hospitals), and (d) worked in any RN job role (e.g., clinical nurses, nurse practitioners, nurse managers). Duplicates were removed by the lead author, and the initial review of titles and abstracts of articles that met the inclusion criteria was conducted by the lead author and one coauthor independently.

The article selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. Overall, 1,745 articles were identified in a search of the three databases. After screening titles and abstracts, 17 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this scoping review.

Quality Appraisal

The methodologic quality of the reviews was assessed using the JBI (2000) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies and the JBI Checklist for Qualitative Research (Lockwood et al., 2015). The JBI critical appraisal tools assess the methodologic quality of studies and whether possible biases are addressed appropriately. These tools evaluate the extent to which the study participants, study designs, research settings, measurements, confounding factors, and statistical strategies are validly defined or clearly identified (Lockwood et al., 2020). The quality of the qualitative and cross-sectional studies was given a score out of 10 points or 8 points, respectively. Quality ratings were performed by two researchers in a double-coded manner. Disagreement was resolved through discussion until a consensus was achieved.

No critical appraisal was completed for the five studies consisting of narrative experiences because no tools could be identified to assess the quality of narrative studies. These were not considered qualitative research studies because they did not involve “an iterative process in which improved understanding to the scientific community is achieved by making new significant distinctions resulting from getting closer to the phenomenon studied” (Aspers & Corte, 2019, p. 139). Although critical appraisal was not done, the narratives were determined to be of immense value for better understanding the issue and were carefully incorporated into the results of this review.

Data Abstraction and Synthesis

Studies that met the inclusion criteria were charted in a standard format to provide summaries and independently cross-checked for accuracy by two researchers. Information extracted from each study included the following: authors, year published, country in which the study was conducted, aims, study design, sample, sample size, and major findings, when applicable. Two researchers independently reviewed the studies, grouped the key findings on work-related concepts, and identified research gaps. For qualitative research studies, the themes were identified and described. For studies featuring personal narrative experiences, descriptions of work experiences following a cancer diagnosis were extracted. For quantitative research studies, the primary findings regarding work-related outcomes were extracted. After all studies were reviewed, the extracted data were compared by two researchers to synthesize the similarities and differences among the findings. If disagreements arose, two researchers discussed and reproofed the full texts to reach a complete consensus. Quotations from qualitative studies that best exemplified the key concepts in the results were chosen after agreement among the researchers.

Findings

Study Characteristics

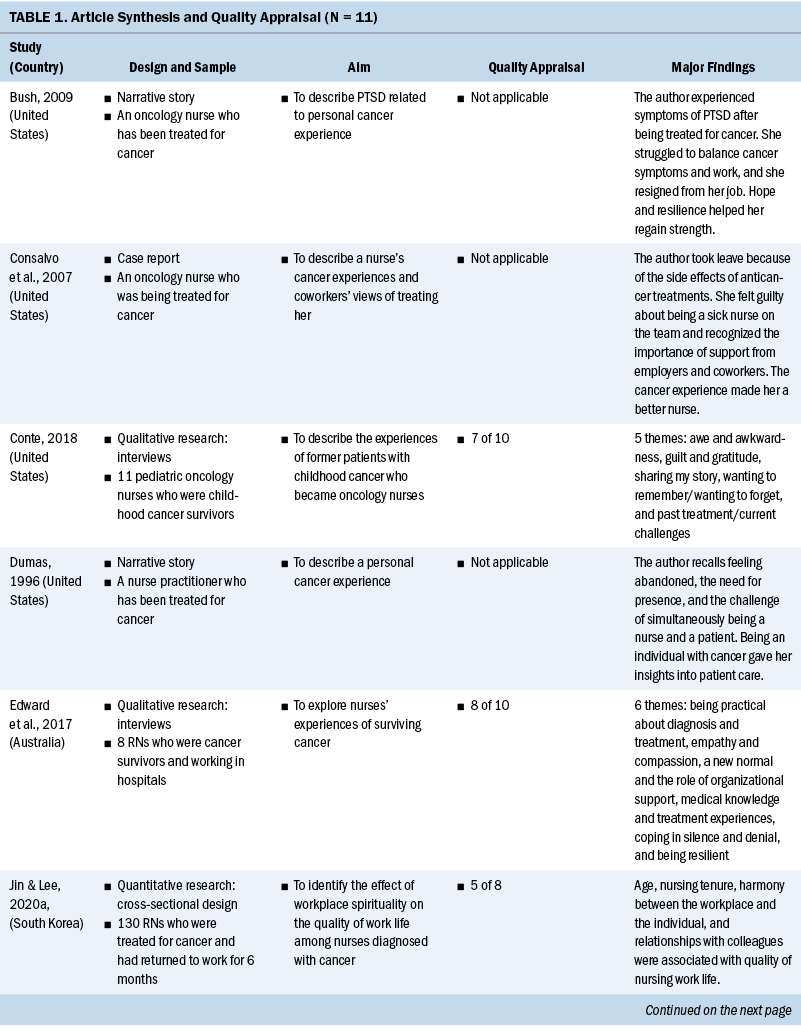

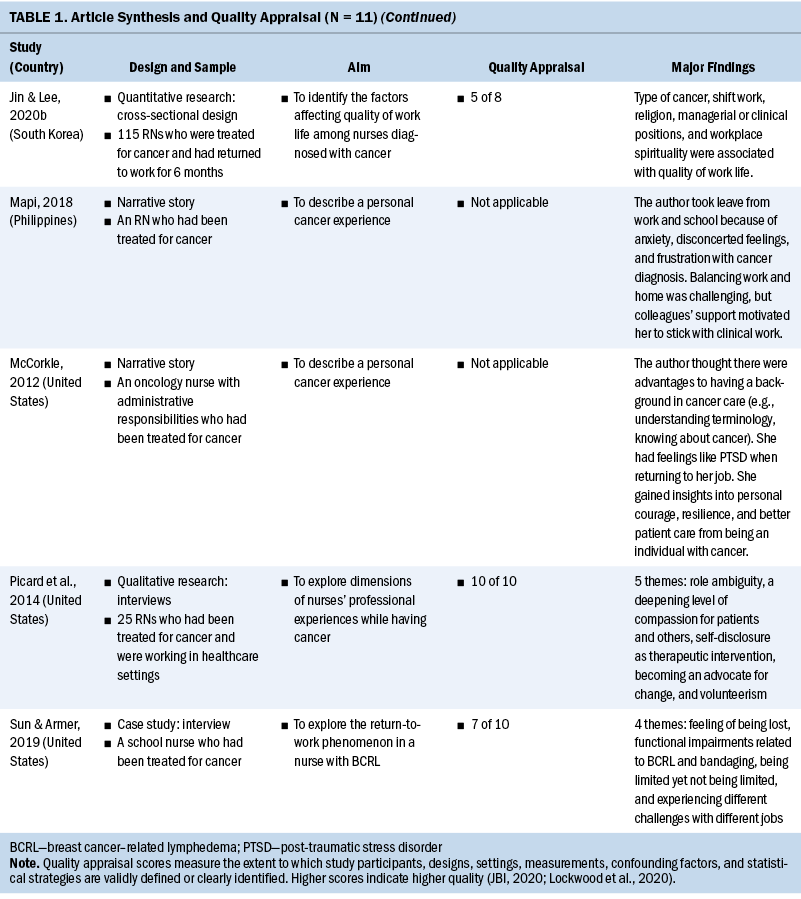

Eleven studies were included in this scoping review. The oldest was published in 1996, and the most recent was published in 2020. The studies were from the following four countries: the United States (n = 7), South Korea (n = 2), the Philippines (n = 1), and Australia (n = 1). Of the studies in the review, nine were qualitative and two were quantitative. Of the nine qualitative studies, five were narrative descriptions of a single nurse’s experience, and four were interview studies employing phenomenologic (n = 3) and exploratory research design (n = 1). Both quantitative studies were cross-sectional studies conducted in a series by the same research team in South Korea.

Sample sizes ranged from 1 to 130 (median = 1, interquartile range = 1–25). Studies on nurses’ cancer experiences had a sample size of 1, interview studies had a sample size of 1–25, and cross-sectional studies had a sample size of 115–130. Most participants were female (n = 293 of 295, 99%). The predominant cancer type of the participants was breast cancer (n = 159 of 295, 54%), followed by thyroid cancer, and most participants were diagnosed with early-stage cancer. Nurses’ roles reported in the studies covered a range of clinical and managerial positions, including staff nurses and nurse managers. The work settings varied and included internal medicine, surgical, psychiatric, pediatric, and oncology units; schools; community clinics; and management.

Quality Appraisal

Table 1 presents the quality assessment results on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies (JBI, 2020) and the JBI Checklist for Qualitative Research (Lockwood et al., 2015). The scores of the qualitative research studies ranged from 7 to 10 (of 10 points), and the scores of both quantitative research studies were 5 (of 8 points).

Work-Related Concepts

After reviewing 11 studies, the following four major work-related concepts were identified: (a) role adjustments at work, describing nurses’ perceptions of being a nurse and a patient at the same time; (b) cancer impacts on work, describing how cancer symptoms influence nurses’ careers; (c) organizational support, describing the role of organizational support in nurses’ work; and (d) translating insights gained from cancer experience into work, describing how nurses translate their cancer experience into nursing practice.

Role adjustments at work: Of the 11 studies, 5 included nurses’ perceptions of role adjustments at work after a cancer diagnosis. Nurses with cancer valued working to create a sense of normalcy and as a distraction from their cancer (Picard et al., 2004), although some were concerned about whether they could successfully return to work (Bush, 2009). At work, nurses struggled to maintain a sense of privacy and composure with their dual roles as nurses and as individuals with cancer (Picard et al., 2004). Some nurses were willing to share their cancer stories with their coworkers, and others preferred to keep their distance to avoid inquiries and maintain normalcy. Simultaneously being individuals with cancer and healthcare providers confused some nurses and made it difficult for them to stop acting like nurses when receiving cancer treatments, which caused emotional and physical distress (Edward et al., 2017; Picard et al., 2004). Mapi (2018) described role reversal as a “disconcerting and frustrating experience” (p. 292) and “both familiar and foreign, as the nurse gives up the authority and control in caring for others while submitting oneself as a patient” (p. 292). Nurses who worked in oncology settings mentioned that sometimes the work environment caused them to recall their memories of the cancer experience and made them feel uncomfortable (Conte, 2018). One nurse described the following experience of role ambiguity:

I would feel most unsettled; I would walk in and see somebody that was a caretaker [her oncology provider], who was very giving, and then they would make me feel settled, and, well, then why do you feel this way? I guess ambiguousness about my role. Who was I? When I would walk through the door every day at [the hospital], I had the impression or impact of . . . what am I? Am I patient or am I a nurse? (Picard et al., 2004, p. 538)

Cancer impacts on work: All studies addressed the impacts of symptoms and treatment side effects related to cancer on nurses’ work. Nurses reported having distressing symptoms, reduced function, and post-traumatic stress symptoms at work. A cross-sectional study suggested that fatigue and job stress significantly contributed to nurses’ worse quality of work life (Jin & Lee, 2020b). The physical and psychological effects of cancer symptoms and treatment side effects challenged these nurses’ day-to-day work (Conte, 2018). Some nurses decided to resign, take a short break, or stay in the nursing profession but change their positions or career paths (Bush, 2009; Consalvo et al., 2007; Mapi, 2018; Sun & Armer, 2019). For example, a nurse with breast cancer–related lymphedema reported difficulties typing on the computer, carrying, lifting, writing, and doing other routine work (Sun & Armer, 2019). Functional impairments decreased nurses’ willingness to remain in nursing positions. Nurses also reported experiencing emotional exhaustion following cancer treatment and post-traumatic stress symptoms at work (McCorkle, 2012; Sun & Armer, 2019). However, some nurses viewed their nursing background as a benefit because it allowed them to quickly understand their disease, treatments, side effects, and prognosis, even if their professional experience could not fully prepare them for the challenges of being a patient with cancer (Edward et al., 2017; McCorkle, 2012). Nurses were required to develop emotional, physical, and work adjustments to manage the impact of cancer treatment on their work. One nurse reported needing to spend additional energy to complete nursing tasks and provide patient care:

I fully expected to recover completely from my breast cancer. The treatment seemed like an enormous inconvenience, but never did I feel my life would end prematurely. So, I was surprised when I returned to my clinical responsibilities and had feelings of being overwhelmed, almost panicked. I was finding it increasingly difficult to listen to patients share their problems. I didn’t know what was happening to me. (McCorkle, 2012, p. 245)

Organizational support: Of the 11 studies, 5 included content about the value of organizational support. Nurses with cancer indicated that organizational support played an essential role in their cancer journey. Sufficient organizational support could motivate them to return to or stay at work (Mapi, 2018). Most nurses indicated that they received support from their coworkers or manager during treatment. Being able to adjust work hours and shifts was very helpful for nurses with cancer to take time for treatments (Consalvo et al., 2007; Edward et al., 2017). Coworkers supported nurses with cancer by donating their time off or sharing their responsibilities (Consalvo et al., 2007; McCorkle, 2012). A cross-sectional study suggested that nurses with cancer who were older or had worked for a longer time were more likely to have better interactions with the job environment, better relationships with colleagues, and a more harmonious relationship with the workplace (Jin & Lee, 2020b). Interactions with the job environment and relationships with colleagues were significant factors contributing to the quality of nursing work life (Jin & Lee, 2020a). The following story illustrates this:

I needed to come back to work. . . . I didn’t have a life not working. . . . Everybody was really supportive in looking after me when I came back [to work]. . . . If I got really tired, they were happy for me to go home early, or if I was having [radiation therapy] . . . they’ve facilitated it. (Edward et al., 2017, p. 1,172)

Translating insights from cancer experience into work: Of the 11 studies, 6 mentioned that nurses perceived their cancer experience as improving their nursing skill set. Nurses with cancer used the language of deepening compassion, disclosure, advocacy, and understanding to describe changes to their nursing practice. Dumas (1996) shared that the role shift from being a nurse to being an individual with cancer improved her ability to advocate for patients and communicate with patients and their families. Cancer experiences empowered nurses to become active listeners when patients and their families were expressing their needs (McCorkle, 2012; Picard et al., 2004), and these experiences gave a sense of presence to nurses to support others getting through difficult situations (Picard et al., 2004). Many nurses described disclosing their own cancer journeys and emotions to their patients in case it might convey therapeutic benefits (Consalvo et al., 2007; Conte, 2018; Picard et al., 2004).

Nurses with cancer often became public advocates for patient care from a broader perspective. In some instances, they led research in cancer care (Mapi, 2018), advocated for changes in patient care, negotiated safe work environments, and created patient resources to provide quality care (Picard et al., 2004). In addition, some nurses volunteered to join fundraising activities, run patient support groups, or serve as counselors in cancer care organizations (Picard et al., 2004). One nurse describes the experience of increased empathy and compassion:

I don’t think I had the same empathy for [patients] because I never saw them long term. It had definitely changed my perception on what people actually have to live with. . . . All the side effects, complications, and ongoing appointments . . . [were] something I hadn’t thought about with patients. (Edward et al., 2017, p. 1,172)

Knowledge Gaps

Results of this scoping review show that a limited number of studies have considered work issues for nurses with cancer. Although the quality of studies is inconsistent, they present a preliminary understanding of what work was like after nurses were diagnosed with cancer. These studies draw attention to work issues for nurses with cancer and offer a starting point for researchers to build on. However, more research is required to comprehend the facilitators and difficulties of returning to or staying at work for nurses with cancer. This review reveals several methodologic and research gaps. First, the included studies were published sporadically across the past 20 years. The outdated research results might not sufficiently reflect the situations nurses with cancer face at work, particularly because the healthcare industry has changed dramatically following the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the studies in this scoping review uniformly lack a theoretical or conceptual framework, and there was minimal synthesis of main ideas across nurse-focused cancer studies, resulting in a failure to provide a comprehensive understanding of the work experiences of nurses with cancer. A framework can provide a clear picture linking major factors related to certain phenomena and draw relationships among these factors, which can pave the way to develop targeted, effective interventions. In addition, a framework can help identify nurses at high risk for worse health outcomes. Most existing research articles are qualitative studies, which indicates the need for more quantitative research studies to complement the current findings. Additional quantitative research can explore contributing factors to adverse work experiences and health-related outcomes among nurses with cancer. Third, there was no clear information regarding the participants’ demographic characteristics in most of the studies, raising concerns that the existing literature may not address the diversity of experiences and backgrounds among nurses with cancer.

Discussion

This scoping review maps out key concepts shared among studies focused on nurses with cancer, which consist of positive and negative aspects of having a nursing background when facing a cancer diagnosis. The four major concepts identified in this review introduce the ways that nurses adjust to being a patient, the influence of cancer on their nursing work, the importance of support from their workplace, and the ways nurses apply their personal cancer experiences to change their care practice.

Two of the four work-related concepts identified in this review are novel: role adjustments at work and translating insights gained from cancer experience to work practice. These two concepts were not reported in work-related research on general cancer populations. Future research should include these concepts in identifying and developing ways to manage work-related issues faced by nurses with cancer. A nursing background may benefit some nurses with a cancer diagnosis by helping them understand medical terms and clinical details, but it may also cause unique challenges. Nurses described hoping to maintain their work routines but found it challenging to acclimate to the role of being a patient in addition to handling nursing responsibilities. For some nurses who returned to work, the cancer diagnosis and treatment experience positively informed their nursing practice. This “two-world knowledge” (Picard et al., 2004, p. 537) enabled them to provide more compassionate and enhanced care. A successful return to work improved not only their physical and psychological well-being but also their professional well-being.

The concept of how cancer affects the work experience is deeply entwined with nurses’ cancer- and treatment-related symptoms. The most common symptoms discussed in the studies in this scoping review were fatigue, reduced physical function, and emotional distress (e.g., post-traumatic stress symptoms). The effects of other prevalent, distressing symptoms among the general cancer population on nurses’ professional experiences were not discussed, including cognitive decline and depressive symptoms (Butow et al., 2020; Dorland et al., 2018; Duijts et al., 2014; Jin & Lee, 2020b; Tan et al., 2021). In addition, survivors’ demographic and medical factors, such as age, cancer type, income, and education level, as well as support and culture in the workplace, may correlate with their work-related outcomes (Blinder & Gany, 2020; Butow et al., 2020; Cohen et al., 2021; de Boer et al., 2020). The studies included in this scoping review suggest the necessity of receiving work accommodations and support from nurses’ coworkers and managers. Appropriate work adjustments may motivate and support nurses with cancer to continue their nursing careers. However, little is discussed about the contributing factors of common cancer symptoms to nurses’ work experience and the extent to which these may affect nurses’ needs for work accommodations. Of note, a wider range of elements including financial issues, social context, and cultural and policy expectations (Butow et al., 2020) are scarcely discussed in studies of nurses’ work after a cancer diagnosis.

The designs of studies included in this review were confined to qualitative and cross-sectional approaches, and the studies were conducted individually and sporadically across time. With limited work-related research studying nurses with cancer, a theoretical framework defining the key factors associated with the effects of a cancer diagnosis on the work experience among this population might be helpful to guide future research. Researchers should conduct qualitative studies of work issues among diverse groups of nurses with cancer because of rapidly changing work environments following the COVID-19 pandemic. Larger-scale surveys and longitudinal studies will help build evidence for the barriers and facilitators to providing support for nurses with cancer considering staying in the healthcare workforce. These studies could also focus on the relationships among work experience and health outcomes to clarify intervention targets and inform long-term outcomes.

Limitations

This scoping review has a few limitations. This review looked at only articles published in English and available through electronic databases and did not contain conference abstracts or other research projects not listed in databases. The broadly defined concepts, including work-related issues and nurses with cancer, limited the researchers’ ability to draw specific conclusions and suggestions based on cancer types, work settings, health-related outcomes, and other factors.

Implications for Nursing

Insights gained from this scoping review can serve as a reference for healthcare administrators and policymakers to build a supportive work environment for nurses with cancer. These findings underscore the need for additional research to support nurses in addressing their cancer symptoms at work, helping with role adjustments, ensuring that appropriate and adequate work accommodations are provided, and engaging in reforming quality patient care. Illuminating the challenges and additional support needs at work for nurses with cancer will help ensure that their health and well-being are proactively managed so that they can fully reintegrate into the nursing profession.

Conclusion

The findings of this review demonstrate that little research is currently available to clearly map the challenges that nurses face at work after a cancer diagnosis. Researchers should consider building from the following key concepts identified in this scoping review when developing additional research: (a) role adjustments at work, (b) cancer impacts on work, (c) organizational support, and (d) translating insights gained from cancer experience into work. A guiding framework and recruitment of more diverse participants would be necessary for researchers who plan to explore and quantify the work challenges experienced by nurses with cancer.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Cancer Survivorship HUB in the School of Nursing at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania.

About the Authors

Kai-Lin You, MSN, RN, is a PhD candidate; Meredith H. Cummings, BSN, RN, OCN®, is a PhD student; Catherine M. Bender, PhD, RN, FAAN, is the Nancy Glunt Hoffman Endowed Chair in Oncology Nursing and a professor in the Department of Health and Community Systems and in the Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Laura A. Fennimore, DNP, RN, NEA-BC, is a professor, Margaret Q. Rosenzweig, PhD, CRNP-C, AOCNP®, is a professor, and Andrew M. Dierkes, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor, all in the Department of Acute and Tertiary Care, all in the School of Nursing; Ketki D. Raina, PhD, ORT/L, FAOTA, is an associate professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy in the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and the vice chair for academic affairs; and Teresa Hagan Thomas, PhD, RN, is an associate professor in the Department of Health Promotion and Development in the School of Nursing and a member of the Palliative Research Center in the School of Medicine, all at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. No financial relationships to disclose. You, Bender, and Thomas contributed to the conceptualization and design. You and Cummings completed the data collection and provided the analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. You can be reached at kailinyou@pitt.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted May 2023. Accepted August 6, 2023.)

References

Andel, S.A., Tedone, A.M., Shen, W., & Arvan, M.L. (2022). Safety implications of different forms of understaffing among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(1), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14952

Aspers, P., & Corte, U. (2019). What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology, 42(2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7

Blinder, V.S., & Gany, F.M. (2020). Impact of cancer on employment. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(4), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01856

Buchan, J., Catton, H., & Shaffer, F.A. (2022). Sustain and retain in 2022 and beyond. International Council of Nurses. https://www.icn.ch/node/1463

Bush, N.J. (2009). Post-traumatic stress disorder related to the cancer experience. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(4), 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1188/09.ONF.395-400

Butow, P., Laidsaar-Powell, R., Konings, S., Lim, C.Y.S., & Koczwara, B. (2020). Return to work after a cancer diagnosis: A meta-review of reviews and a meta-synthesis of recent qualitative studies. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 14(2), 114–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00828-z

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Adult physical inactivity prevalence maps by race/ethnicity. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/inactivity-prevalence-maps/in…

Cohen, M., Yagil, D., & Carel, R. (2021). A multidisciplinary working model for promoting return to work of cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29, 5151–5160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06074-3

Consalvo, K.E., Piscitelli, L.D., Williamson, L., Policarpo, G.D., Englander, M., Lyons, K., . . . Lynch, M.P. (2007). Treating one of our own. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11(2), 227–231. https://doi.org/10.1188/07.CJON.227-231

Conte, T.M. (2018). From patient to provider: The lived experience of pediatric oncology survivors who work as pediatric oncology nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 35(6), 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454218787449

de Boer, A.G., Torp, S., Popa, A., Horsboel, T., Zadnik, V., Rottenberg, Y., . . . Sharp, L. (2020). Long-term work retention after treatment for cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 14(2), 135–150.

Dorland, H.F., Abma, F.I., Van Zon, S.K.R., Stewart, R.E., Amick, B.C., Ranchor, A.V., . . . Bültmann, U. (2018). Fatigue and depressive symptoms improve but remain negatively related to work functioning over 18 months after return to work in cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 12(3), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11764-018-0676-X

Duijts, S.F.A., van Egmond, M.P., Spelten, E., van Muijen, P., Anema, J.R., & van der Beek, A.J. (2014). Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 23(5), 481–492. https://doi.org/10.1002/PON.3467

Dumas, M.A. (1996). What it’s like to belong to the cancer club. American Journal of Nursing, 96(4), 40–42.

Edward, K.-L., Giandinoto, J.A., & McFarland, J. (2017). Analysis of the experiences of nurses who return to nursing after cancer. British Journal of Nursing, 26(21), 1170–1175. https://doi.org/10.12968/BJON.2017.26.21.1170

Ekpanyaskul, C., & Sangrajrang, S. (2018). Cancer incidence among healthcare workers in cancer centers: A 14-year retrospective cohort study in Thailand. Annals of Global Health, 84(3), 429. https://doi.org/10.29024/AOGH.2324

Ferlay, J., Ervik, M., Lam, F., Colombet, M., Mery, L., Piñeros, M., . . . Bray, F. (2023). Global cancer observatory: Cancer today. International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today

Friedenreich, C.M., Ryder-Burbidge, C., & McNeil, J. (2021). Physical activity, obesity and sedentary behavior in cancer etiology: Epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Molecular Oncology, 15(3), 790–800. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12772

Galanis, P., Vraka, I., Fragkou, D., Bilali, A., & Kaitelidou, D. (2021). Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(8), 3286–3302.

Gómez-Salgado, J., Fagundo-Rivera, J., Ortega-Moreno, M., Allande-Cussó, R., Ayuso-Murillo, D., & Ruiz-Frutos, C. (2021). Night work and breast cancer risk in nurses: Multifactorial risk analysis. Cancers, 13(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061470

Goss, C., Leverment, I.M.G., & de Bono, A.M. (2014). Breast cancer and work outcomes in health care workers. Occupational Medicine, 64(8), 635–637. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu122

Guy, G.P., Jr., Ekwueme, D.U., Yabroff, K.R., Dowling, E.C., Li, C., Rodriguez, J.L., . . . Virgo, K.S. (2013). Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(30), 3749–3757.

Haddad, L.M., Annamaraju, P., & Toney-Butler, T.J. (2023). Nursing shortage. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved July 5, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493175

JBI. (2020). Critical appraisal tools. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

Jin, J.H., & Lee, E.J. (2020a). Effect of workplace spirituality on quality of work life of nurse cancer survivors in South Korea. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 7(4), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_36_20

Jin, J.H., & Lee, E.J. (2020b). Factors affecting quality of work life in a sample of cancer survivor female nurses. Medicina, 56(12), 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina56120721

Kurtzman, E.T., Ghazal, L.V., Girouard, S., Ma, C., Martin, B., McGee, B.T., . . . Germack, H.-L. (2022). Nursing workforce challenges in the postpandemic world. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 13(2), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(22)00061-8

Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000062

Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Munn, Z., Rittenmeyer, L., Salmond, S., Bjerrum, M., . . . Stannard, D. (2020). Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-03

Mapi, N.S. (2018). A nurse’s journey with cancer. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 5(3), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_10_18

McCorkle, R. (2012). Cancer nurse as cancer survivor. Cancer Nursing, 35(3), 245–246. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824d2b71

McPeake, J., Mikkelsen, M.E., Quasim, T., Hibbert, E., Cannon, P., Shaw, M., . . . Haines, K.J. (2019). Return to employment after critical illness and its association with psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 16(10), 1304–1311. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201903-248OC

Mols, F., Tomalin, B., Pearce, A., Kaambwa, B., & Koczwara, B. (2020). Financial toxicity and employment status in cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28, 5693–5708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05719-z

Munn, Z., Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Nekhlyudov, L., Walker, R., Ziebell, R., Rabin, B., Nutt, S., & Chubak, J. (2016). Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: Results from a multisite study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10(6), 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11764-016-0554-3

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., . . . Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Papantoniou, K., Devore, E.E., Massa, J., Strohmaier, S., Vetter, C., Yang, L., . . . Schernhammer, E.S. (2018). Rotating night shift work and colorectal cancer risk in the nurses’ health studies. International Journal of Cancer, 143(11), 2709–2717. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31655

Peters, M.D.J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A.C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Picard, C., Agretelis, J., & DeMarco, R.F. (2004). Nurse experiences as cancer survivors: Part II—Professional. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(3), 537–542. https://doi.org/10.1188/04.ONF.537-542

Purdue, M.P., Hutchings, S.J., Rushton, L., & Silverman, D.T. (2015). The proportion of cancer attributable to occupational exposures. Annals of Epidemiology, 25(3), 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.009

Ratner, P.A., Spinelli, J.J., Beking, K., Lorenzi, M., Chow, Y., Teschke, K., . . . Dimich-Ward, H. (2010). Cancer incidence and adverse pregnancy outcome in registered nurses potentially exposed to antineoplastic drugs. BMC Nursing, 9, 15.

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2017). Obesity. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/obesity

Ross, A., Yang, L., Wehrlen, L., Perez, A., Farmer, N., & Bevans, M. (2019). Nurses and health-promoting self-care: Do we practice what we preach? Journal of Nursing Management, 27(3), 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/JONM.12718

Seifart, U., & Schmielau, J. (2017). Return to work of cancer survivors. Oncology Research and Treatment, 40(12), 760–763. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485079

Smiley, R.A., Ruttinger, C., Oliveira, C.M., Hudson, L.R., Allgeyer, R., Reneau, K.A., . . . Alexander, M. (2021). The 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 12(1, Suppl.), S1–S96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S21558256(21)00027-2

Sun, Y., & Armer, J.M. (2019). A nurse’s twenty-four-year journey with breast cancer-related lymphedema. Work, 63(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-192904

Tan, C.J., Yip, S.Y.C., Chan, R.J., Chew, L., & Chan, A. (2021). Investigating how cancer-related symptoms influence work outcomes among cancer survivors: A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 16(5), 1065–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01097-5

Tricco, A.C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K.K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., . . . Straus, S.E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Wegrzyn, L.R., Tamimi, R.M., Rosner, B.A., Brown, S.B., Stevens, R.G., Eliassen, A.H., . . . Schernhammer, E.S. (2017). Rotating night-shift work and the risk of breast cancer in the nurses’ health studies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 186(5), 532–540. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx140

Wills, J., Hancock, C., & Nuttall, M. (2020). The health of the nursing workforce: A survey of national nurse associations. International Nursing Review, 67(2), 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12586

World Health Organization. (2020). State of the world’s nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331677/9789240003279-e…