Food Safety

While it has often been said you can’t test quality into a product, nevertheless, a good testing program can minimize the severity of a recall.

to Avoid Costly Recalls

Use food testing

Two recent recalls in late 2023, both involving foreign suppliers, seem to show that either no testing was done onsite or on entrance to the U.S.—or it wasn’t done properly—otherwise the FDA recalls probably wouldn’t have been necessary. The first recall involved high levels of lead in the cinnamon used in an Ecuador processor’s cinnamon-flavored applesauce, and the second, Salmonella on/in cantaloupes from Mexico.

Yet another recall by the Quaker Oats Company dated December 15, 2023 involved specific granola bars and granola cereals “because they have the potential to be contaminated with salmonella.” Then, almost a month later—January 11, 2024— the company expanded its December recall to include additional cereals, bars and snacks including Quaker Cinnamon Oatmeal Squares, which is a favorite cereal of mine.

Food testing is a vital process in the food manufacturing chain that ensures the safety and quality of food products, thereby protecting public health. Image courtesy of Getty Images / gorodenkoff

by Wayne Labs, Senior Contributing Technical Editor

While I appreciate the abundance of caution, the number of products and UPC codes involved seems lengthy with some use-by dates extending to October of this year, which has to be quite costly to Quaker. Could this recall have been kept smaller or eliminated altogether with more judicious ingredient sampling/testing and better record keeping and training?

“When it comes to contamination, vigilance and consistency are always the best policies,” says Naren Meruva, Waters Corporation director of food and environmental markets. Even a trusted supplier can face unexpected challenges with contamination. Spot checks and composite sampling (pulling random samples from each supplier, combining and testing) can reduce the burden of testing each ingredient shipment, while providing added confidence that raw materials meet the operation’s minimum quality and safety criteria.

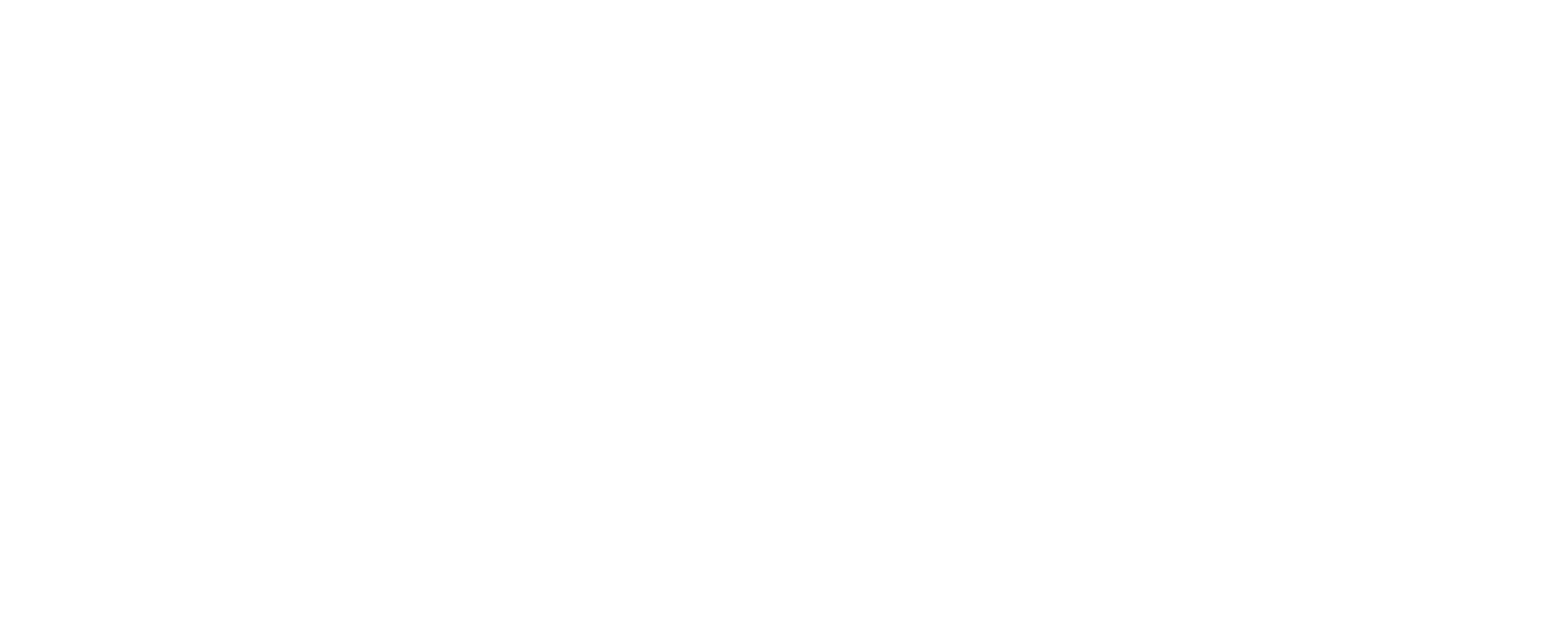

The FDA’s Closer to Zero uses a science-based, iterative approach for achieving continual improvements over time. Image courtesy of the FDA

Testing for Lead, Other Heavy Metals

“In 2021, the FDA announced its program: Closer to Zero. This work is aimed at reducing the amount of lead, arsenic, cadmium and mercury found in food, with a focus on food eaten by babies and young children,” says Dominika Gruszecka, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, food & consumer products market manager. “The program is cyclical, so that proposed limits and actions are based on current science, and when those limits are finalized over time, we can see what improvements are available and continue to apply the newest research to get our food supply closer and closer to being lead free.”

In the case of the lead in the applesauce, the FDA went to visit the Ecuador processor and tested the applesauce—and found 2270 and 5110 ppm (parts per million) of lead concentration in two applesauce samples. Safe levels, according to Codex Alimentarius, are a maximum of 2.5 ppm. EPA considers the action level for lead in drinking water to be 15 ppb (parts per billion) of lead, and the FDA has set action levels for less than 10 to 20 ppb in apple juice, depending on the type of juice.

Is there a quick indicator test that could have found the high lead content in the applesauce, or is analytical instrumentation the better option? “A commercially available red-coloring lead pen test instruction manual states that if a faint color change is observed, it indicates greater than 0.1% lead,” says Gruszecka. While different brands of indicator tests will have slightly different limits, this example serves as an estimate. That 0.1% converts to 1000 ppm, far more than the safe levels for food, as described above. However, the indicator test would have discovered the exceedingly high levels of lead (2270 and 5510 ppm) reported by the FDA in the applesauce. But a lead-specific test wouldn’t find other heavy metals.

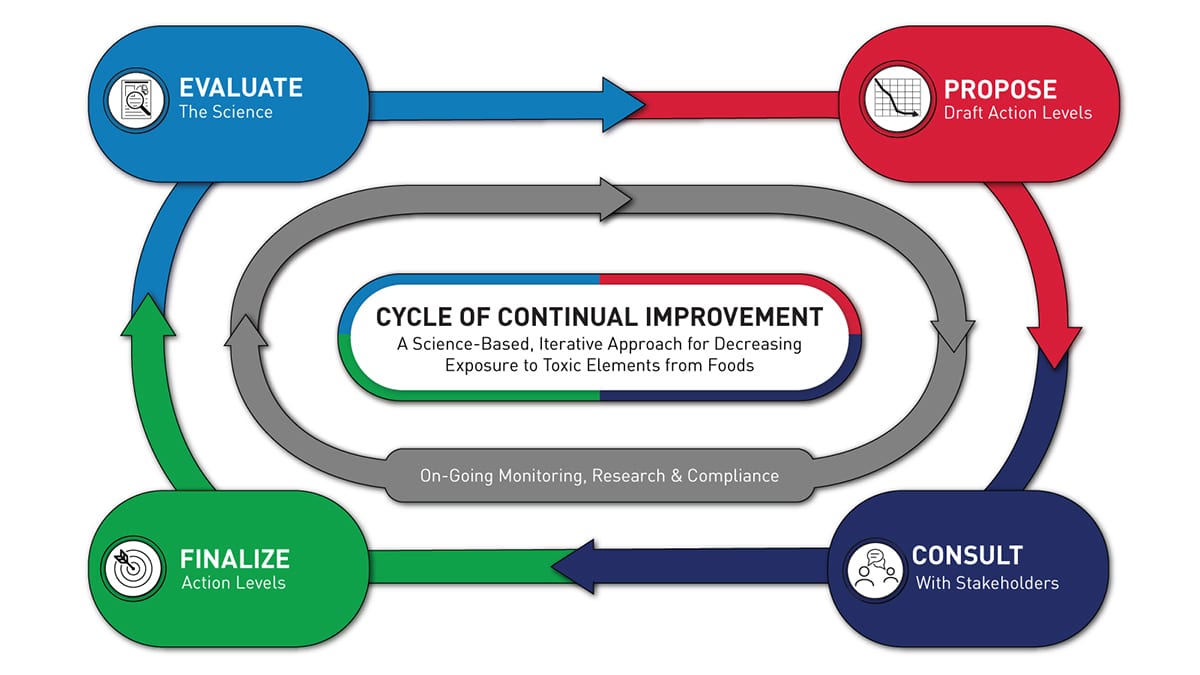

“An inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICPMS) is the most commonly used equipment for testing small quantities of lead, like those required by the EPA,” says Gruszecka. “We at Shimadzu have examined a number of fruit juices for heavy metals and provided the results and method using our ICPMS as a guide for labs. Our results for the fruit juices were reported in micrograms per liter; 1 µg/L is equal to 0.001 ppm, or 1 ppb. The report showed a detection limit of 0.09 ppb for lead, making this instrument over ten million times as sensitive as the color change indicator tests. Other heavy metals can be tested by the instrument at the same time, like cadmium, arsenic and nickel. Beneficial minerals like iron can also be tested at the same time.”

The Shimadzu Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS) employs a technique widely used for high-sensitivity analysis of toxic metals. Image courtesy of Shimadzu

“Determining unsafe levels of heavy metals in food and beverage products like juice or applesauce is typically handled by analytical instrumentation, due to the need for high sensitivity and specificity in detecting these contaminants, particularly when they are present at low levels,” says Hakan Gurleyuk, Brooks Applied Labs' technical director. “Using the latest in microwave digestion and triple quadrupole ICP-MS technologies, we provide heavy metals testing services to companies that manufacture, distribute and retail a variety of consumer products."

Gurleyuk continues, "The methods Brooks Applied offers are consistent with those used by regulatory agencies and have been rigorously evaluated as part of our accreditation to the ISO 17025 standard, our participation in the certification of new reference materials, and the proficiency testing arranged by the Baby Food Council.

“Testing multiple heavy metals at the same time does make sense. Many natural ingredients accumulate heavy metals, such as lead, mercury, arsenic and cadmium, from the environment (i.e., the soil, water and air), but determining exactly how much is in a product requires sensitive analytical methods. The frequency of testing can depend on various factors such as the type of product, the potential for contamination and regulatory requirements. Some recommendations suggest systematic testing of food products and potentially contaminated ingredients, but the exact frequency would need to be determined based on the specific circumstances,” adds Gurleyuk.

Resultant levels of heavy metals and other elements found in various fruit juice samples using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICPMS) show sensitivities beyond rapid indicator tests. Image courtesy of Shimazdu

Foreign Suppliers, Food Fraud and Testing?

When a food is imported into the U.S., the U.S.-based owner or consignee is responsible for compliance with the Foreign Supplier Verification Program (FSVP), as detailed in FDA regulation 21 CFR 1, Subpart L. The FSVP rule itself imposes requirements on importers, not foreign suppliers. Nevertheless, importers may make requests from foreign suppliers to assist in meeting the importer’s obligations.

The FSVP regulation stipulates that an FSVP Qualified Individual conduct a Hazard Analysis of the food, approve the supplier and conduct verification activities to ensure the supplier is manufacturing safe food. The FDA defines an FSVP Qualified Individual as someone who “must develop your FSVP and perform each of the activities required under this subpart. A qualified individual must have the education, training, or experience (or a combination thereof) necessary to perform their assigned activities and must be able to read and understand the language of any records that must be reviewed in performing an activity.”

In the situation of the applesauce recall, a likely cause of contamination is from the food manufacturer’s ingredient supplier or its supplier. The FSVP verification activities may include a review of the manufacturer’s supplier program but does not likely include a review of the manufacturer’s individual ingredient suppliers or its sub-suppliers.

Another important note is that the hazard analysis conducted is for hazards that are reasonably likely to occur in a food or in the facility. If there is no historical reference of a hazard occurring, then by definition the hazard was not reasonably likely to occur.

Specific again to the applesauce recall, the FDA is investigating this outbreak as an intentional economically motivated food fraud. This means that the cinnamon was possibly adulterated, counterfeited and/or substituted, either in part or in whole, with the intention of selling the cinnamon at an elevated price. Economically motivated food fraud is the intentional deception or misrepresentation of food products for economic gain. This type of fraud occurs when the food supply chain manipulates or adulterates food products with the primary aim of increasing profits. Economic motives can drive various fraudulent practices, and they may compromise the quality, safety and authenticity of the food supply. Economically motivated food fraud can have serious consequences, including potential health risks for consumers, damage to brand reputation, and economic losses for legitimate producers.

To protect your supply chain, uphold food safety standards and safeguard consumer trust in your products, every food manufacturer should conduct a detailed and well-thought-out Food Fraud Vulnerability and Severity Assessment for each ingredient and supplier. It is through these assessments that you will understand the potential food fraud threats, and then implement mitigation strategies to address each.

While some of these mitigation strategies are preventive in nature, others include testing of high-risk ingredients for adulteration or authenticity.

—Tim Lombardo, Senior Director, EAS Consulting Group

Testing for Listeria and Other Microbiological Contaminants: Indicator Tests or Analytical Instrumentation?

The FDA provides guidelines for testing the foodborne pathogens in its Bacteriological Analytical Manual. Some microbiological contaminants, however, are more challenging than others.

With respect to the recent cantaloupe recall, salmonella caused 302 cases to be reported in 42 states. One might suspect that salmonella or listeria would be picked up in the field and transported to the packing house. You would think that with proper washing, any microbial contaminants would be killed before going out the door to the supply chain, but at Colorado’s Jensen Farms in 2011, cantaloupes were not contaminated with listeria in the field, but were contaminated in the packing house, which stopped using chlorinated water for washing, and listeria were found in puddles on the floor and elsewhere throughout.

“There are indicator microorganism tests that could be performed on the surface of cantaloupes (i.e., Enterobacteriaceae),” says Gabriela Lopez Velasco, senior technical service specialist at Neogen Food Safety. “Studies show that high levels of an indicator may be the result of improper hygienic practices, but this does not necessarily indicate there is a pathogen. The opposite case is also true.

“Continuous pathogen environmental monitoring and testing could have been beneficial in this case,” adds Velasco. “Not all packing houses are equipped to perform this type of testing, so third-party testing through service laboratories is a common option. Today, there are a variety of rapid methods that provide next-day results for environmental samples (i.e., sponges or swabs) as well as finished products.

“Deciding how many tests should be performed depends on the size of the facility and the volume of each lot, among other factors,” continues Velasco. “It is important for food safety managers to consult with a statistician to make sure they are collecting the right number of samples when testing finished products. For testing equipment and environmental monitoring, it is beneficial to map out the facility and equipment to build up a strong sampling plan.”

“Unfortunately, listeria is a persistent pathogen that is challenging to remove once established in facilities, and cantaloupes are likely to be contaminated due to their low acidity,” says M. Lorna De Leoz, Ph.D., Agilent Technologies, Inc. global food segment director. “While rapid tests may provide a quick check for bacterial contamination, more sophisticated analytical equipment may be needed for accurate identification of specific bacteria and their populations. Researchers at University of Florida are using absorbance readers and washers to concentrate and detect low levels of bacterial pathogens in lettuce wash. This technique provides high-quality, high-performance microplate reading at an affordable price.”

The Agilent 7850 ICP-MS system is a powerful tool for the analysis of trace elements in food samples, offering low detection limits and high dynamic range to analyze both trace and major elements in one run. Image courtesy of Agilent

De Leoz adds that researchers at University of Naples are evaluating gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) methods to accurately and rapidly detect volatile organic compounds that may be associated with specific bacterial pathogens in meats.

“It is important for packing houses to have in place robust food safety practices and testing to minimize the risk of bacterial contamination,” says De Leoz. “Third-party testing organizations could be a viable option if the packing house cannot afford conducting in-house tests. Reputable third-party laboratories have the necessary equipment and expertise to conduct the tests. Frequency of tests would depend on various factors such as the risk of contamination, the type of bacteria being tested for and regulatory requirements. Turnaround time for tests vary depending on the type of test and the workload of the testing organization.”

While rapid tests may work in some applications, they won’t provide the detail of analytical instrumentation. “Listeria and other bacteria like salmonella and e. coli can be tested in packing facilities using cartridge style tests, similar to what we used for at-home COVID-19 tests, and cost about the same but may have a longer wait time,” says Shimadzu’s Gruszecka. “While screening for COVID-19, we had a clear sampling location to target—our noses. With a cantaloupe, the testing area becomes much more difficult to sample thoroughly. One option is to use these cartridges for wash water and quarantine fruit by batch. In this case, there is a risk of diluting the wash water beyond the sensitivity of the test. Each cartridge is single use and only dedicated to one type of bacteria. Other bacterial tests require time to grow a sample in an incubator to get a large enough sample to identify.

The Waters LC-MS/MS offers high sensitivity optimized workflows for food safety testing laboratories. Image courtesy of Waters

“Mass spectrometry can be used for screening bacteria, as each type of bacteria has a known structure and mass; however, this method is not yet very popular,” adds Gruszecka. “In mass spectrometry, the targets are broken down and the pieces are separated using electric and magnetic fields, giving more data about the fragments. This lets us develop libraries of data for different compounds, viruses and bacteria, and we can identify them like we use fingerprints to ID people. A popular type of instrument is the MALDI-ToF-MS, which can provide results in seconds instead of minutes.”

In cases where testing cannot be done on-site, third-party testing is an excellent option. Food testing labs undergo strict regulations and proficiency testing to ensure they are providing accurate and precise results. Many testing labs will highlight their turnaround time. The more often tests are done, the easier it is to contain possible outbreaks, adds Gruszecka.

Food Companies and Suppliers on the Same Page

Preventing food contamination—and thus, recalls—is a difficult task for food and beverage processors, says Neogen’s Velasco. Education and awareness should be top priority when working with foreign suppliers to ensure that proper quality and safety requirements for products are being met. Relationships with suppliers should be seen as partnerships rather than simple, transactional operations.

Suppliers must also understand that their products can pose risk to the human population, so it is critical they implement and ensure follow-through of food safety programs, like HACCP and FSMA principles, adds Velasco. Both food processors and suppliers should follow the same programs, otherwise, the correct balance in this important equation (supplier : producer) does not exist. A qualifying supplier program where continuous audits occur is the most beneficial.

Neogen’s Clean-Trace Surface ATP Test Swab contains a chemical that reacts with the sample collected on the swab to produce light. The amount of the light produced is proportional to the degree of potential contamination. Measurement of the light requires the use of a Clean-Trace LM1 Luminometer, and the results are displayed in Relative Light Units (RLU). Image courtesy of Neogen

“Let’s discuss testing programs for a minute—they are very important verification tools to confirm cleaning and sanitation programs, process controls, etc. are working properly,” says Velasco. “However, testing on its own is not the unique element to prevent a recall. Testing should be backed up by a well-implemented food safety plan. In addition, having the right sample collecting procedures in place for raw, processed, environment and finished products is critical in demonstrating that the actions taken to minimize food contamination are working.”

“Having a devoted team to ensure these programs are working correctly and presenting continuous audits to suppliers is essential for executing programs like HACCP. Therefore, I would not say that there is limited time for this team to be on duty,” adds Velasco. “Food safety should never sleep, so active food safety programs should exist on a continual basis.”

Food Companies and the Expense of Testing

The perception of food safety testing programs as an expense is not uncommon among food processors and may be so in foreign countries, says Brooks’ Gurleyuk. This perception can lead to skimping on testing programs. However, the cost of not implementing adequate food safety measures can be far greater, as it can result in foodborne illnesses and economic losses.

Testing labs such as Brooks Applied make it easier for food processors and importers to take testing seriously by offering cost-effective and time-effective customized testing services. Through cost-effective services, education and regulatory measures, testing organizations, industry consultants and instrument manufacturers can help food processors and importers understand the value of these programs and take them seriously.

For some processors, food regulations can be vague and difficult to “translate” into actionable steps in a food facility, says Tim Lombardo, EAS Consulting Group senior director. “Consultants and other experts can certainly help to bridge that gap.”

Companies that invest in analysis and consulting often approach food safety proactively. These manufacturers will look to trends in regulatory enforcement as a means to improve their systems before an issue arises. Other manufacturers take a more reactive approach, spending time and money when issues arise. Of course, a proactive approach is always preferred, adds Lombardo.

Even when processors follow all the prescribed rules, accidents can happen. “In some cases, contaminated products may slip through despite due diligence and following best practices, simply because of the volume of raw materials and ingredients, and the challenge of ensuring a representative sample for a specific lot,” says Waters’ Meruva. For example, a ship carrying 10,000-60,000 tonnes (~2.6M bushels) of maize may be sampled and tested prior to shipment at destination—and receive further scrutiny upon arrival at the processing plant. In the case of aflatoxins, contamination may occur in just a few kernels, or a small area of the shipment, making sampling critical to the quality monitoring process. In fact, scientific studies show that greater than 80% of the error in mycotoxin testing is the result of sampling. Ensuring raw material suppliers are equipped with appropriate knowledge and training will move food processors toward better and more consistent product safety and quality outcomes, adds Meruva.

Food processors and exporters face the challenge of differing food safety standards across different countries and trade regions, often with little clarity on how to meet them. International standardization organizations, such as ISO and AOAC, bring together the subject matter experts from industry, regulatory agencies, instrument manufacturers and testing organizations to develop harmonized analytical methods with global acceptance that benefit all stakeholders and consumers. Testing organizations and instrument manufacturers can help with implementation of these new analytical technologies and methods by training food processors on regulatory testing requirements, says Meruva, driving efficiency through their laboratory operation while managing the cost of testing. FE