What Moneyball-for-Everything Has Done to American Culture

You can make a thing so perfect that it’s ruined.

This is Work in Progress, a newsletter by Derek Thompson about work, technology, and how to solve some of America’s biggest problems. Forwarded this newsletter? Sign up here to get it every week.

The return of the World Series this weekend offers an opportunity to engage in America’s real national pastime: wondering loudly why people don’t like baseball as much as they used to.

Speaking personally, my relationship to the game these days is one of nostalgic befuddlement. The nostalgia part comes from spotless memories of watching Sunday Night Baseball on my parents’ couch, nestled between my dad and my dog: the chintzy ESPN graphics, the theme song that sounded straight out of a video game, the dulcet baritones of the announcers Jon Miller and Joe Morgan. The befuddlement part comes from the fact that, like a lot of people of my generation, I spend a weird amount of time wondering why I don’t spend any amount of time watching baseball anymore.

Possible reasons abound. After the steroid scandals of the 2000s, the stars of my childhood got dragged onto C-SPAN, ceremonially berated for cheating by grumpy old dudes, and blacklisted from the Hall of Fame. Kind of a bummer, to be honest. But on a deeper level, I think what happened is that baseball was colonized by math and got solved like an equation.

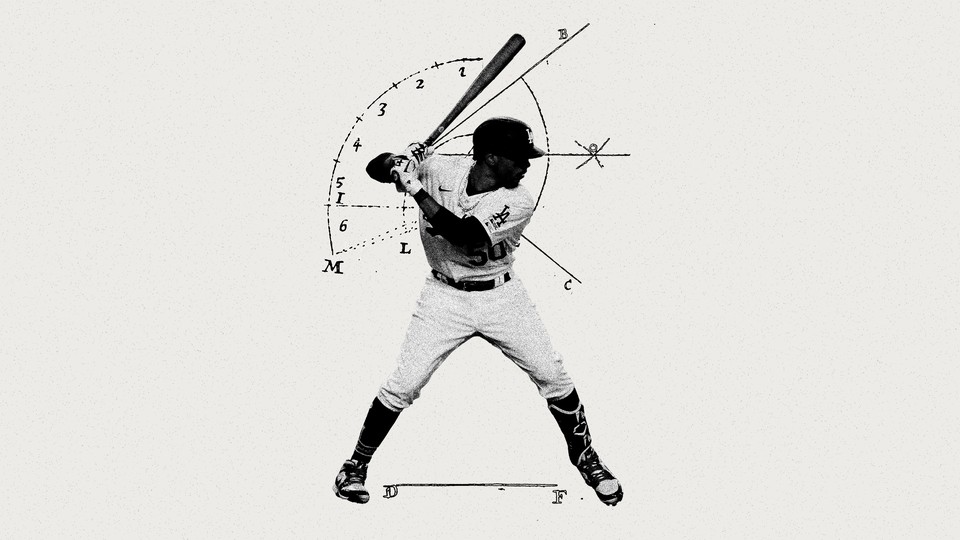

The analytics revolution, which began with the movement known as Moneyball, led to a series of offensive and defensive adjustments that were, let’s say, catastrophically successful. Seeking strikeouts, managers increased the number of pitchers per game and pushed up the average velocity and spin rate per pitcher. Hitters responded by increasing the launch angles of their swings, raising the odds of a home run, but making strikeouts more likely as well. These decisions were all legal, and more important, they were all correct from an analytical and strategic standpoint.

Smarties approached baseball like an equation, optimized for Y, solved for X, and proved in the process that a solved sport is a worse one. The sport that I fell in love with doesn’t really exist anymore. In the 1990s, there were typically 50 percent more hits than strikeouts in each game. Today, there are consistently more strikeouts than hits. Singles have swooned to record lows, and hits per game have plunged to 1910s levels. In the century and a half of MLB history covered by the database Baseball Reference, the 10 years with the most strikeouts per game are the past 10.

The religion scholar James P. Carse wrote that there are two kinds of games in life: finite and infinite. A finite game is played to win; there are clear victors and losers. An infinite game is played to keep playing; the goal is to maximize winning across all participants. Debate is a finite game. Marriage is an infinite game. The midterm elections are finite games. American democracy is an infinite game. A great deal of unnecessary suffering in the world comes from not knowing the difference. A bad fight can destroy a marriage. A challenged election can destabilize a democracy. In baseball, winning the World Series is a finite game, while growing the popularity of Major League Baseball is an infinite game. What happened, I think, is that baseball’s finite game was solved so completely in such a way that the infinite game was lost.

When universal smarts lead to universal strategies, it can lead to a more homogenous product. Take the NBA. When every basketball team wakes up to the calculation that three points is 50 percent more than two points, you get a league-wide blitz of three-point shooting to take advantage of the discrepancy. Before the 2011–12 season, the league as a whole had never averaged more than 20 three-point-shot attempts per game. This year, no team is attempting fewer than 25 threes per game; four teams are attempting more than 40.

As I’ve written before, the quantitative revolution in culture is a living creature that consumes data and spits out homogeneity. Take the music industry. Before the ’90s, music labels routinely lied to Billboard about their sales figures to boost their preferred artists. In 1991, Billboard switched methodologies to use more objective data, including point-of-sale information and radio surveys that didn’t rely on input from the labels. The charts changed overnight. Rock-and-roll bands were toppled, and hip-hop and country surged. When the charts became more honest, they also became more static. Popular songs stick around longer than they used to. One analysis of the history of pop-music styles found that rap and hip-hop have dominated American pop music longer than any other musical genre. As the analytics revolution in music grew, radio playlists became more repetitive, and by some measures, the most popular songs became more similar to one another.

Or take film. As with music, you could certainly make the case that the communications revolution has created an abundance of video content that, in the aggregate, is fantastically diverse. But although the rules for making a viral video, or a critically acclaimed film, are deeply complex, blockbuster movies look a lot like a solved equation. In 2019, the 10 biggest films by domestic box office included two Marvel sequels, two animated-film sequels, a reboot of a ’90s blockbuster, and a Batman spin-off. In 2022, the 10 biggest films by domestic box office included two Marvel sequels, one animated-film sequel, a reboot of a ’90s blockbuster, and a Batman spin-off. Correctly observing that audiences responded predictably to familiar intellectual property, studios invested in a strategy that has squeezed original IP from the top-10 charts. Blockbusters are kinda boring now, not because Hollywood is stupid, but because it got so smart.

Is what I’m complaining about really a problem? Does it actually matter that people watch a lot of Marvel sequels, or that baseball no longer bestrides the national discourse? These issues don’t belong alongside wealth inequality, democratic continuity, or malaria on the spectrum of material problems. But I don’t want to hold cultural analysis ransom to the malaria test. The fact that movies and music aren’t as weighty as mortality is a part of why they are so important. As Larry Kramer wrote of sugar, culture might be the most important thing in life precisely because it’s about living, not just staying alive.

So yes, I care about the dark side of Moneyball. The Nobel laureate particle physicist Frank Wilczek once said that beauty exists as a dance between opposite forces. First, he said, beauty benefits from symmetry, which he defined as “change without change.” If you rotate a circle, it remains a circle, just as reversing the sides of an equation still reveals a truth (2+2=4, and 4=2+2). But beauty also draws from what Wilczek calls “exuberance,” or emergent complexity. Looking up at the interior of a mosque or a cathedral, or gazing at a classic Picasso or Pollock painting, you are seeing neither utter chaos nor a simple symmetry, but rather a kind of synthesis; an artistic dizziness bounded within a sense of order, which gives the whole work an appealing comprehensibility.

Cultural Moneyballism, in this light, sacrifices exuberance for the sake of formulaic symmetry. It sacrifices diversity for the sake of familiarity. It solves finite games at the expense of infinite games. Its genius dulls the rough edges of entertainment. I think that’s worth caring about. It is definitely worth asking the question: In a world that will only become more influenced by mathematical intelligence, can we ruin culture through our attempts to perfect it?

Want to discuss the future of business, technology, and the abundance agenda? Join Derek Thompson and other experts for The Atlantic’s first Progress Summit in Los Angeles on December 13. Free virtual and in-person passes available here.