Why Colombia's protests are unlikely to fizzle out

EPA

EPAMore than 50 people have died since a wave of protests started to sweep across Colombia at the end of April.

Protesters have blocked key roads leading to shortages of fuel and food in some areas and there have been violent clashes between the security forces and demonstrators.

The government has been holding talks with protest leaders but with more and more groups joining in the demonstrations, the demands of those who have taken to the streets have widened and a quick resolution seems unlikely.

Here's a look at what triggered the protests and how they have grown.

How did they start?

The demonstrations started on 28 April and were initially in opposition to a proposed tax reform.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government argued that the reform was key to mitigating Colombia's economic crisis. Its gross domestic product dropped by 6.8% last year, the deepest crash in half a century. Unemployment shot up as the coronavirus pandemic wreaked havoc on the economy.

The proposed reform would have lowered the threshold at which salaries are taxed, affecting anyone with a monthly income of 2.6m pesos ($684; £493) or more. It would also have eliminated many of the current exemptions enjoyed by individuals, as well as increasing taxes imposed on businesses.

The first rallies, organised by the country's biggest trade unions, were also joined by many middle-class people who feared the changes could see them slip into poverty. Tens of thousands of people marched in the capital Bogotá, while demonstrations were also held in other major cities and smaller towns.

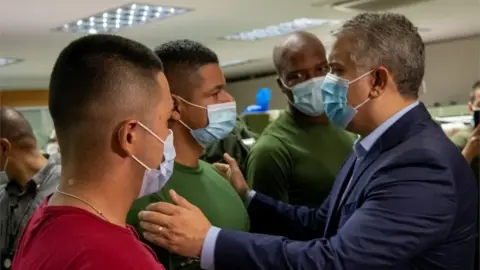

After four days of protests, President Iván Duque announced he would withdraw the bill.

How did protests escalate?

From the start, there was a big police presence at the marches as they were held in defiance of a court order which had ruled that they should be postponed due to the high incidence of Covid-19.

Human rights groups reported that riot police had not only used tear gas to disperse protesters but in some cases shot live ammunition.

Footage shared on social media showed violent clashes and on 3 May, the ombudsman's office confirmed that 16 civilians and one police officer had died since the protests began.

So rather than abating after the cancellation of the tax reform, the protests intensified.

A month on, the official figure of those who have died in the protests stood at 59 people. More than 2,300 civilians and members of the security forces have been injured.

EPA

EPAThere have also been marches by Colombians who oppose the protests. On Sunday, thousands took to the streets of major cities to demand an end to the roadblocks and violent clashes.

What do protesters want?

While this year's protests were triggered by the now-suspended tax reform, they are a continuation of nationwide anti-government protests which began in November 2019.

Back then, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets after a call by an umbrella group calling itself the National Strike Committee.

The same group is behind the current protests and its demands are as varied as the people who are joining in the marches.

One of the issues which has most angered protesters is the actions of riot police.

The United Nations human rights chief, Michelle Bachelet, has called on the Colombian government to launch an independent inquiry into the deaths of protesters in the city of Cali, where clashes between demonstrators and the security forces have been most deadly.

Ms Bachelet said her office had received reports of more than a dozen people being killed in the south-western city in one day on 28 May.

Police violence has hit the headlines before. Last September, news that a man died after being tasered by police in Bogotá triggered violent protests in which at least seven people were killed.

And in 2019, tens of thousands marched after the death of Dilan Cruz, a teenager who was hit by projectile fired by riot police at an anti-government protest.

The protesters want the riot police to be disbanded and for all members of the security forces to be held accountable by an independent body rather than by military courts.

The defence minister said the protests had been infiltrated by members of left-wing rebel groups and pointed to incidents of vandalism and looting.

But protesters argue it is time the security forces, which for decades were engaged in an armed conflict with powerful rebel groups, treated them like citizens rather than enemies.

What role does poverty play?

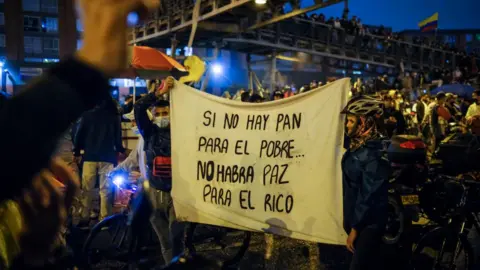

Many of the protesters' demands are rooted in Colombia's high levels of inequality. The pandemic has made the lives of many Colombians more precarious, with 3.6 million people being pushed into poverty.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn cities like Quibdó, in the north, 30% of people live in extreme poverty and even in Medellín, Colombia's economic powerhouse, that figure amounts to 9%, according to official sources.

Some of the protesters argue that only the introduction of a universal basic income will ease inequality while Colombia's young are demanding that tuition fees be dropped so that more can access university education.

Indigenous groups have also joined in the protests. They are among those hardest hit by the continuing violence in rural areas where dissident members of the Farc rebel group fight the security forces as well as rival armed groups.

Twenty-two indigenous leaders are among 67 rights defenders killed this year, according to a tally by peace institute Indepaz, and Colombians are demanding that the state do more to protect those standing up for rural, indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities.

What does the government say?

President Duque has demanded that the protesters lift all the roadblocks they have erected before any concessions to the protesters can be considered.

Reuters

ReutersThe roadblocks have caused huge losses to the economy. Farmers say they cannot get their goods to markets, transport businesses have been caught in endless tailbacks and some residents of major cities say they feel like they are under siege.

On 28 May, President Duque announced that he would deploy 7,000 troops to clear the main highways.

The president has also ruled out one of the protesters' main demands - the dismantling of the riot police, meaning that the talks between the two sides have all but stalled.