Mildly depressed? Antidepressants may not improve your quality of life

- While antidepressants are widely used to treat depression, their effectiveness has been controversial.

- A new study found that patients with depression who use antidepressants do not experience improved health-related quality of life compared to patients who don't use antidepressants.

- The finding suggests that doctors might want to try non-pharmaceutical interventions, like cognitive behavioral therapy and lifestyle improvements, before prescribing antidepressants — at least for patients with mild depression.

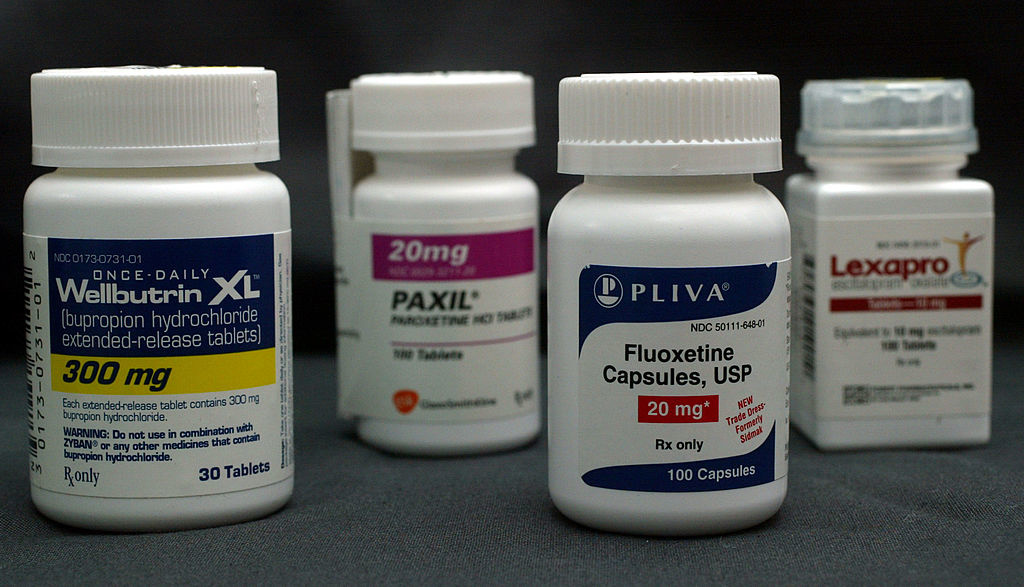

About 13% of American adults use antidepressants, according to the most recent CDC statistics. But despite the drugs’ ubiquity, their overall effectiveness remains somewhat controversial.

Prior studies have raised concerns that antidepressants‘ benefits were overstated on account of publication bias — positive studies got published while negative ones were shelved.

So, a few years ago, an influential group of researchers tasked themselves with finding all of the published and unpublished double-blind randomized controlled trials of antidepressants and then analyzing them together to see whether there’s convincing evidence that antidepressants truly worked.

The hunt turned up 522 trials involving more than 116,000 participants.

Doctor Aaron E. Caroll, a pediatrician and Vice Chair for Health Policy and Outcomes Research at Indiana University, summed up the results to The New York Times:

“The reassuring news is that all of the antidepressants were more effective than placebos… The bad news is that even though there were statistically significant differences, the effect sizes were still mostly modest. The benefits also applied only to people who were suffering from major depression, specifically in the short term.”

Carroll’s overall takeaway:

“We still do not know how well antidepressants work for those with milder symptoms that fall short of major depression, especially if patients have been on the drugs for months or even years.”

A study recently published in the journal PLoS ONE addresses this dilemma, and the results don’t augur well for antidepressants.

Health-related quality of life

Scientists primarily based out of King Saud University in Saudi Arabia utilized data from the United States’ Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), perhaps the most complete source of data on the cost and use of health care in the U.S. Armed with MEPS, the researchers compared the change in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) – an individual’s perceived physical and mental health – between patients with depressive disorder who used antidepressants and depressed patients who did not. The data they analyzed included more than 17 million adults diagnosed with depression, with a two-year follow-up.

Controlling for various confounders like age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, poverty level, and insurance coverage, the scientists found that people who used antidepressants reported slightly greater improvement in mental health-related quality of life compared to those who did not, but the difference did not reach statistical significance, so therefore it could just be due to chance. Moreover, patients on antidepressants reported that their physical health quality of life slightly worsened compared to patients not on the drugs, but again, the difference was not statistically significant.

The researchers interpreted this as a null result.

“The real-world effect of using antidepressant medications does not continue to improve patients’ HRQoL over time, as the change in HRQoL was comparable to patients who did not use any antidepressant medications,” they wrote.

This by no means suggests that people on antidepressants should stop taking them. The drugs have been shown to be more effective against severe depression, and this new study doesn’t dispute that.

“We still need our patients with depression to continue using their antidepressant medications,” the authors added in a statement. “With that being said, the role of cognitive and behavioral interventions on the long term-management of depression needs to be further evaluated in an efforts to improve the ultimate goal of care for these patients; improving their overall quality of life.”

These salubrious interventions include cognitive behavioral therapy, better sleep habits, a healthier diet, and regular exercise, all of which can alleviate symptoms of depression and boost well-being. The researchers suggest that, at least for people with mild depression, these kinds of remedies should be the first options to treating their symptoms, rather than antidepressants.