A remarkably mutated coronavirus variant classified as BA.2.86 seized scientists' attention last week as it popped up in four countries, including the US.

So far, the overall risk posed by the new subvariant is unclear. It's possible it could lead to a new wave of infection; it's also possible (perhaps most likely) it could fizzle out completely. Scientists simply don't have enough information to know. But, what is very clear is that the current precipitous decline in coronavirus variant monitoring is extremely risky.

In a single week, BA.2.86 was detected in four different countries, but there are only six genetic sequences of the variant overall—three from Denmark, and one each from Israel, the UK, and the US (Michigan). The six detections suggest established international distribution and swift spread. It's likely that more cases will be identified. But, with such scant data, little else can be said of the variant's transmission or possible distribution.

Altered adversary

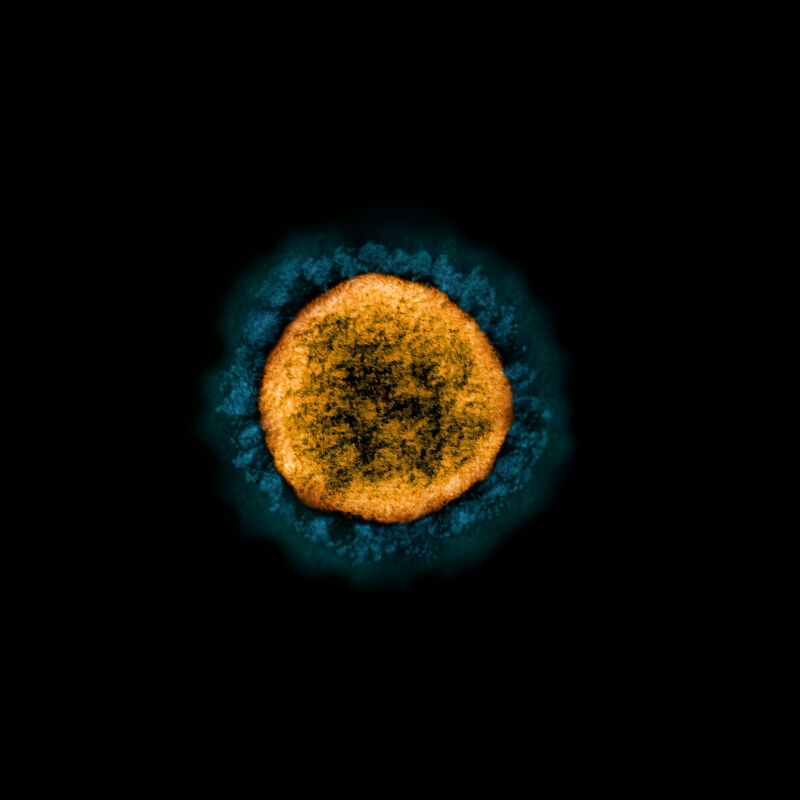

What grabbed quick attention is BA.2.86's large number of mutations, particularly in the genetic code for its critical spike protein—the protein the virus uses to latch onto and enter human cells. BA.2.86 has 34 mutations in its spike gene relative to BA.2, the omicron sublineage from which it descended. This number of spike mutations between BA.2.86 and BA.2 is chillingly similar to the number of mutations seen between the original omicron (BA.1) and the ancestral Wuhan strain. The evolutionary jump from Wuhan to BA.1 caused a towering peak of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations in early 2022. But, experts are skeptical that BA.2.86 could produce a rivaling wave, given the extensive levels of immunity in the population from both repeat vaccinations and infections.

In preliminary examinations of BA.2.86's mutations, viral genetics experts say it looks adapted to escape neutralizing antibodies—even those spurred or boosted by exposure to a currently circulating omicron sublineage, XBB.1.5. Many of the spike mutations seen in the new variant are linked to antibody escape, according to an analysis by Jesse Bloom, a viral evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle. Bloom's analysis suggests that BA.2.86's overall mutations give it at least as much antibody-escaping abilities as XBB.1.5, relative to BA.2. And BA.2.86's mutations give it the ability to escape some antibodies against XBB.1.5, which is the variant targeted by the upcoming fall booster vaccines. Of course, neutralizing antibodies are not the totality of immune responses; there are non-neutralizing antibodies as well as cell-based protections that can work to prevent severe disease.

So far, it's unknown whether BA.2.86 can cause more severe disease than existing variants, though the tiny bit of data so far suggests that it does not. Denmark's Statens Serum Institute, which has identified three of the world's six cases, said on X last week that "there is no indication that the new variant causes severe illness." It also noted that the patients were not immunocompromised and did not have epidemiological links between them. In fact, all six cases are unrelated to each other. In a report by the UK Health Security Agency on Friday, officials also reported that the UK case had no recent travel history, suggesting domestic transmission.

Perhaps the biggest question left unanswered about BA.2.86 is how well it will spread relative to other variants in circulation, namely XBB.1.5, EG.5, FL.1.5.1, and others. For BA.2.86 to cause its own wave, it must couple its antibody-escaping abilities with changes that make it more easily transmissible than other variants. So far, there's simply not enough data to know if this is the case or not.

Still, experts like Bloom are not alarmed. "The most likely scenario is this variant is less transmissible than current dominant variants, and so never spreads widely. This is the fate of most new SARS-CoV-2 variants," he wrote in his analysis.

But even if BA.2.86 does what Bloom sees as mostly likely—fade away to an esoteric evolutionary anomaly—it should still raise alarm over the current state of our virus monitoring, as experts at the World Health Organization have repeatedly warned about.

Data decline

Part of the reason there is so little data on BA.2.86 is that there is relatively little data on circulating variants in general. In early 2022, at the height of pandemic genomic surveillance, scientists worldwide submitted nearly 100,000 coronavirus genetic sequences per week to the public genomic database (GISAID). In the past month, however, weekly GISAID submissions have averaged around just 5,000.

In the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has likewise seen a perilous drop in monitoring. In early 2022, the agency collected data from nearly 100,000 COVID-19 tests per week. Now, amid a summer wave with test positivity on the rise again, the test volume is just 40,000. And the agency only has enough genomic surveillance data to estimate variant prevalence for three of the country's 10 health regions.

In October of last year, as experts were wary of a winter wave of COVID-19, Maria Van Kerkhove, WHO's technical lead for COVID-19, warned in a press briefing that the surveillance landscape had "changed drastically."

"The number of sequences that the world and our expert networks are evaluating has dropped by more than 90 percent since the start of the year. That limits our ability to really track each of these [omicron subvariants]," she said at the time.

But things have only gotten worse since then. In October 2022, for instance, scientists submitted over 20,000 coronavirus sequences per week to GISAID, compared with the current average of around 5,000.

"We need to ensure that sequencing continues. The virus is evolving," Van Kerkhove said in a press briefing on August 9, addressing concerns about the previous variant making headlines, EG.5, which WHO had then classified as a "variant of interest." Last week, WHO classified BA.2.86 as a "variant under monitoring."

"The virus is circulating in every country and EG.5 is one of the latest variants of interest that we're classifying. This will continue and this is what we have to prepare for," she added. Currently, no single variant is dominant anywhere, and the virus is circulating essentially unchecked.

reader comments

200