Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Emma Watkins. Emma is Head of Marketing and Communications at technology consultancy 67 Bricks, having previously worked for over a decade in various roles in marketing at IOP Publishing.

Since the release of ChatGPT, the world has been inundated with blog posts and LinkedIn opinions about the future of AI in every industry you can imagine.

The truth is, regardless of this sudden buzz, this technology is not new. Web crawlers and other AI-based information extraction programs have been an essential part of the internet since the late 90s, and TiVo started using AI to make program recommendations for users back in 2006. And like every piece of technological advancement from the printing press to the home computer, changes to every industry (including scholarly publishing) are inevitable. The good news is, the impact of these changes rests on how creative humans can be at harnessing novel technology to the greatest benefit. The challenge, then, for publishers, is to ensure they are the creative adopters leading the charge, as opposed to being trampled by better customer experiences created by other technological disruptors.

But how?

The basic benefits of AI and Machine Learning are twofold;

- They can make standardized and data-intensive tasks faster (not necessarily more accurate — you get out what you put in!)

- They can lower the cost of prediction

If we take these two tenets, we can see two major themes in the ways publishers can look to innovate; efficiency and market intelligence. Let’s explore them.

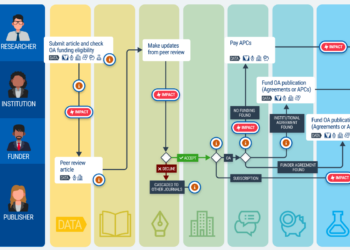

Making peer review better

There’s a lot of process-driven activity in publishing, and peer review is just one place where there are many opportunities for increased efficiency. Considering the size of the content datasets available at most publishers just on their own journals and books, using machine learning to search for relevant reviewers, or assess whether a manuscript’s topic is suitable for a given journal, seems to make sense. Taken further, for manuscripts which are rejected on scope or novelty, but which are still sound research, automatically being able to offer other titles within the publisher’s portfolio that may be more suitable can reduce the number of papers being lost to competitors and keep decision-making down where the reviews are able to be reused. In a post-Covid world where the speed of critical research reaching end users has become paramount, taking advantage of these efficiencies will become more and more expected by those end users. That being said, making any editorial decisions based solely on Machine Learning has all the potential pitfalls of baking in existing bias from the data it has been trained on, and so it’s unlikely to ever be the only information that Editors should consider when making publishing decisions.

Fighting fraud

As the number of papers being submitted to publishers continues to grow, being careful about preventing unethical behavior while not increasing receipt-to-publish times becomes more challenging. Here AI is also part of the challenge — there are now plenty of ways for people to create images and text using AI which would challenge most peer reviewers’ ability to detect. But, like with the numerous chatGPT checkers that are springing up, there are tools available to help people detect content created by an algorithm. It’s early days for their accuracy, but as with all things when it comes to technology the trend is generally positive. These tools, which can enhance human decision-making, will shore up the integrity of the published record without adding time to the process.

Creating useful content

AI is already being used for the auto-generation of abstracts and metadata, for example for legacy articles or book chapters you wish to repackage or drive usage of. A gap in the market that could be incredibly beneficial is to quickly summarize research papers and automatically generate press releases and content marketing. Creating quick lay summaries for work that would be useful for other fields or for which there is a high public interest (climate science or medical research for example) would break down barriers and encourage more interdisciplinary work to the benefit of all. For marketers facing the ‘blank page problem’, using a Large Language Model to help generate content ideas, refine copy, and write confidently in technical areas can up the pace and responsiveness of campaigns.

Beyond benefits to publishers, there are also potential benefits for researchers as well. One of the UN Sustainable Development Goals is ‘Reduced Inequalities’, which AI and ML are well placed to support. Much of academic discourse, particularly in the written scholarly record, exists in English. For those for whom English is not a first, or even second or third, language, this can provide additional barriers to publication and impact. Language editing tools trained on the academic record could help researchers to improve their writing so the clarity of their thought is not lost within their text, helping to narrow the divide between native English speakers and the rest of the world. It should be noted that for these researchers, care should be taken to ensure that meaning and accuracy have not been damaged by the algorithm!

Predicting winning content

Imagine being able to spot which research papers are likely to cause a stir in either their fields or in the public eye. For years now Hollywood has been using AI to help predict which pitches should be greenlit. And in 2020, researchers in Finland successfully created an ML-based language model to predict the performance of news articles prior to publishing, which one of the companies used to test the model found so valuable they decided to develop it further. Using similar tools to predict which papers will gain the most attention and should be prioritized for press releases, email newsletters, social media boosting, and other content marketing campaigns could be an invaluable way to cut through the noise felt in most publisher marketing departments. That being said, making decisions based on models of old content can mean that truly surprising and novel results may not be flagged; which is where human intervention and expertise will always be necessary.

Combining data with editorial strategy

Predicting trends doesn’t have to stop with individual papers and their potential for popularity. It could also be used to help people to weigh up the merits of different future journal launches or book series, or develop new products, or pitch a topic for a new conference, or decide which regions to recruit new editorial board members… the list goes on. As always, combining the amount of data that can be analyzed at pace by AI with human insight and ingenuity is the best possible way to create a bright future.

To conclude

So what does all this mean? Stephen Hawking told us that “AI will be either the best, or the worst thing, ever to happen to humanity”. You could easily swap ‘humanity’ for ‘publishing’ in that quote and capture much of the thoughts expressed today by colleagues across the publishing industry. I’d like to think that for human knowledge sharing, it’s going to be a net positive result in the end. Whether publishers can innovate quickly enough to be part of that result is what truly remains to be seen, and is already an open discussion elsewhere on The Scholarly Kitchen.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Guest Post: AI and Scholarly Publishing — A (Slightly) Hopeful View"

What is new is that the technology has been put in the hands of the consumer. That by itself will lead to less work for content creators. Secondly, all businesses that can cut costs by replacing employees with AI will start to do so. Thirdly, all content will be uploaded to Open Source versions of the current well-known AI services, for further analysis and various types of re-use. For some situations, starting your own AI service is like starting YouTube, too expensive. So right now, the increased popularity of AI tools will lead to ‘a lot less’ and ‘a little bit more’ for existing content creators. Major AI service providers will follow a financial path similar to Spotify. Rights owners can choose to work with ‘Verified AI’ services as opposed to infringing AI services and find ways for further monetization of their content. Other than that, some AI services have the potential to become the new Chegg or the new Sci-hub. Time will tell.

Emma, many thanks for your (definitely) more forward looking and positive article on AI and how Publishers should view this “new” tool. Context vs. angst… much appreciated. Patrick

While machine-learning and many other AI pattern-matching systems are not new, generative-AI, that is, systems with the capability to produce fluent text / code/ realistic-seeming pictures *is* in fact fundamentally new — it only started emerging over the past few years. And its takeup by the public is newer still, dating from the release of ChatGPT as a free tool six months ago.