For more than three years, Dr. Christopher Ohl has been treating Covid patients in the intensive care unit at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist in North Carolina.

Lately, however, he's noticed a change: His patients are nowhere as sick as they used to be.

"What we're seeing now is our patients who are admitted with Covid pneumonia in the ICU tend to respond faster to treatment, they're less likely to die, and they're more likely to get discharged earlier," said Ohl, also a professor of infectious diseases at Wake Forest University School of Medicine. "They don't seem to be as sick with it as they were two years ago."

It's a trend other ICU doctors have noticed, too, even as Covid hospitalizations continue to rise.

Severe complications and extended hospital stays are less common now compared with several years ago, said Dr. Cameron Wolfe, an infectious disease expert and an associate professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine.

"Generally speaking, they don't get that really horrid hyper-inflammatory disease that we were seeing a few years ago," Wolfe said. "We still see it to some extent, but it's not as dramatic as it was."

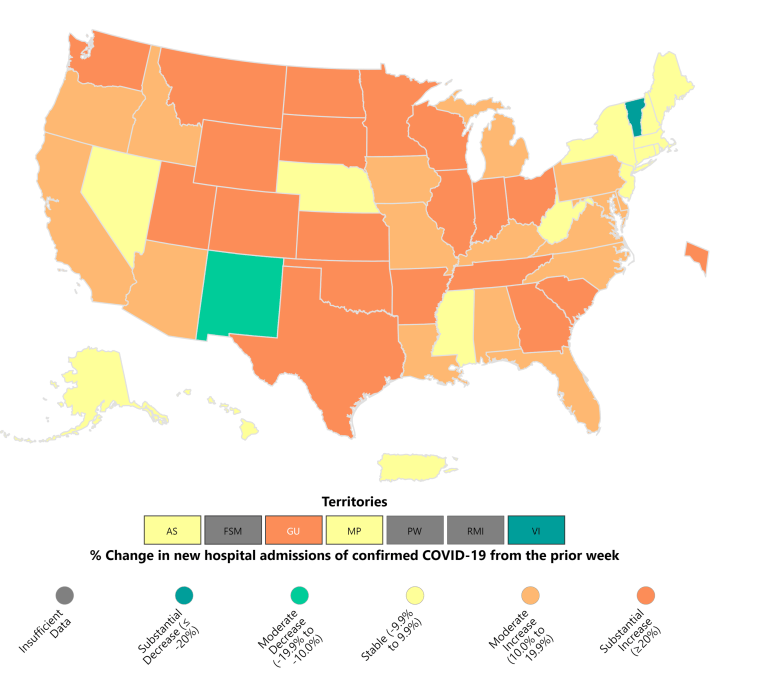

Just over 17,400 people in the U.S. were hospitalized with Covid the week ending Aug. 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a 15.7% increase over the week prior. Hospitalizations have been rising since early July, after hitting an all-time low.

There are several reasons Covid patients may no longer be as sick as in previous years, even when they end up hospitalized.

The latest omicron subvariants that have evolved and are now circulating "are not as nasty" as previous variants like delta, or the original strain that first swept the country, Ohl said.

In 2020, severely ill Covid patients were showing up at hospitals with symptoms like unusual blood clots. Some would experience about a week of moderate illness before their health suddenly derailed, prompting stays in the intensive care unit.

These outcomes are much less common, Wolfe said.

Another change: People with underlying chronic health conditions, such as obesity and Type 2 diabetes, do not seem to make up the bulk of hospitalized Covid patients as much as they did early in the pandemic.

"In the beginning, that's who it really targeted," said Dr. Joshua Denson, director of medical critical care at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans.

But now, Denson said, "I do think we've crossed a threshold where, even with these new variants, it doesn't seem to be affecting that population like it did before."

People also have access now to the antiviral Paxlovid, which has been shown to keep people out of the hospital.

What's more, the vast majority of Americans — 95%, according to the CDC — has some level of protective immunity to the virus, whether through vaccination, infection or both.

"When you start to get sick with Covid, our immune systems are engaged. Rather than becoming part of the problem, they're more part of the solution," Ohl said.

Those who are hospitalized now with Covid tend to have weakened immune systems, such as older adults, certain cancer patients and people who have had organ transplants.

"Everybody I've seen come to the ICU in the last six months is immunosuppressed in some way," said Dr. Ken Lyn-Kew, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health in Denver.

Many hospitalized Covid patients have blood-related cancers, Ohl said, such as leukemia, lymphoma and myeloma. Others have had bone marrow transplants or an organ transplant. Their immune systems are weaker, even if they've been vaccinated.

"In other words," said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, "these are people who did not respond optimally to the vaccine, or in whom their protection has waned since their last dose."

The patients who do end up hospitalized with Covid often need help breathing, said Dr. Bernard Camins, medical director for infection prevention at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

"For the most part, if someone were to come in for Covid, it's really about oxygenation," Camins said. "They need oxygen that you can't get at home."

After this latest increase in Covid-related hospitalizations, Schaffner said he expects another rise in the middle of winter, which "could be a little bit higher."

Still, "we don't expect anything like what we had last year or the year before," he said.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.